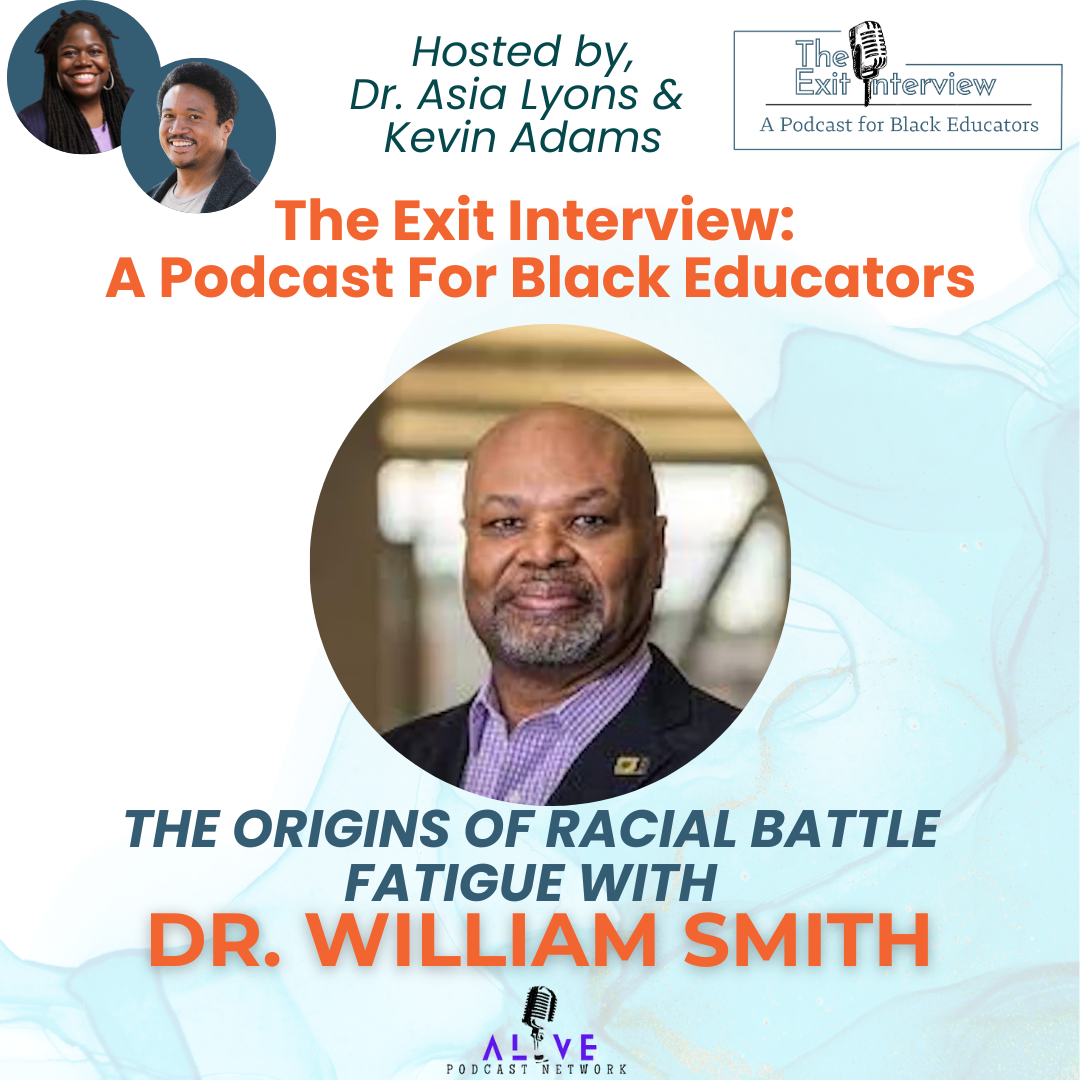

The Origins of Racial Battle Fatigue with Dr. William Smith

This is a real special episode of the Exit Interview! Asia and Kevin talk with Dr. William A. Smith, professor of Education and Ethnic Studies at the University of Utah. Dr. Smith, who developed some of the most profound research around the concept of Racial Battle Fatigue, shares his research, insights and experiences tracking this phenomenon.

In this profound and wide-ranging conversation, Dr. Smith discusses a veritable library of topics, so many that we decided to expand this conversation to two parts (Part II will be out this summer–stay tuned!). He shares his perspectives on the positioning of school leaders and teachers in regard to revolutionary action. He shares his thoughts on Black representation in film as a pacifying force. He names the genocidal actions taken against Black people both past and present.

Throughout this conversation with this next level scholar, the learning is strong, the struggle In contextualized, and the inspiration is total. Tune in!

Episode Title: The Origins of Racial Battle Fatigue with Dr. William Smith

Hosts: Kevin Adams & Dr. Asia Lyons

Guest: Dr. William A. Smith, Professor at the University of Utah

Episode Overview

In this powerful episode, Kevin and Asia welcome Dr. William A. Smith, the scholar who coined the term "racial battle fatigue." The conversation dives deep into the origins, symptoms, and far-reaching impacts of racial battle fatigue, especially within educational spaces. Dr. Smith shares his personal journey, clarifies misconceptions about his work, and offers practical advice for educators, administrators, and the Black community at large.

Guest Bio

Dr. William A. Smith is a professor at the University of Utah with over two decades of experience. His groundbreaking research on racial battle fatigue has influenced academic and public discourse worldwide. Dr. Smith’s work focuses on the psychological, emotional, and physiological effects of racism, particularly on Black faculty, staff, and students.

Main Topics & Segment Breakdown

1. Introduction & Housekeeping

- Kevin and Asia welcome listeners, share social media links, and thank Patreon supporters.

- Announcement: The "We Got This" book giveaway for new patrons.

2. Meet Dr. William Smith

- Dr. Smith’s background: Chicago roots, academic journey, and move to Utah.

- Early research focus on Black professors in higher education.

3. The Origins of Racial Battle Fatigue

- Clarifying misconceptions about when and how the term was introduced.

- Initial resistance and skepticism from academic audiences.

- The growing recognition and international impact of the concept.

4. Understanding Racial Battle Fatigue

- Three major categories of symptoms:

- Psychological (frustration, defensiveness, mood changes, anxiety)

- Emotional/Behavioral (imposter syndrome, withdrawal, maladaptive coping)

- Physiological (headaches, sleep disturbances, illness)

- The importance of recognizing and naming these experiences.

5. The Role of Environment and Community

- The need for culturally affirming spaces at home and work.

- The impact of media and cultural narratives on Black consciousness.

- The importance of critical thinking and resisting negative portrayals.

6. Genocide, Education, and Resistance

- Dr. Smith’s perspective on systemic attacks on the Black mind and body.

- The role of education in liberation and the dangers of cultural depression.

- The need for independent Black schools and community-based education.

7. Administrators, Policy, and Disaggregation

- Why the term "BIPOC" can be problematic—importance of disaggregating data.

- Recommendations for school leaders to better support Black educators and students.

- The value Black teachers bring to all students, regardless of background.

8. Healing, Self-Care, and Community Action

- Practical advice: healthy eating, sleep, communal support, and cultural traditions.

- The cyclical nature of stress within Black families and communities.

- The importance of organizations and collective action for lasting change.

9. Book Recommendations & Resources

- "Harriet, the Moses of Her People" by Sarah Hopkins Bradford

- "Blues People" by LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka)

- "The Autobiography of Assata Shakur"

- Works by Michelle Alexander and Joseph Baldwin

Notable Quotes

- “Racism is a violent act and the body codes racism as an attack.”

- “We have to control our education and learn from history.”

- “Administrators can do revolutionary work because they control the development of minds.”

- “If you want to keep information from Black people, put it in a book.”

Calls to Action

- Leave a five-star review on Apple Podcasts to help others find the show.

- Share this episode with educators, administrators, and anyone interested in racial justice and education.

Thank you for listening!

If you enjoyed this episode, let us know on social media and stay tuned for more insightful conversations.

First of all.... have you signed up for our newsletter, Black Educators, Be Well? Why wait?

Amidst all the conversations about recruiting Black educators, where are the discussions about retention? The Exit Interview podcast was created to elevate the stories of Black educators who have been pushed out of the classroom and central office while experiencing racism-related stress and racial battle fatigue.

The Exit Interview Podcast is for current and former Black educators. It is also for school districts, teachers' unions, families, and others interested in better understanding the challenges of retaining Black people in education.

Please enjoy the episode.

Peace out,

Dr. Asia Lyons

The Origins of Racial Battle Fatigue with Dr. William Smith (1)

Intro: [00:00:00] Like

Kevin Adams: what is good? How is everybody doing? It is Kevin Adams and I'm back with the amazing Asia Lion Asia. How are you?

Dr. Asia Lyons: I can't complain. A beautiful Sunday here in Colorado.

Kevin Adams: The weather keeps getting nicer and nicer, uh, after all that snow that we ended up march with, but, uh, I'm loving it. Uh, but, uh, we are excited to be here again for episode five of the exit interview.

Um, so, uh, remember, you guys can follow us at two Dope Teachers on Instagram and Twitter, and you can like us on facebook@facebook.com slash two Dope teachers and a mic. Our [00:01:00] email address is two dope teachers@gmail.com and you could listen to us on Apple Spotify podcast or@mrmunoz.org org.org. You like how I said that Asia, if you do listen to us on Apple, give us a five star review, please, please give us a review.

It helps people find us and it gets our content out. And finally, if you wanna support us, because, uh, it takes money to do this amazing stuff that we're doing here. At, uh, the exit interview. Uh, head on over to our patreon.com/two Dope Teachers where you can become a Patreon, a Patron for just $5 a month.

And, uh, we hate to tell you guys this, but the book, the, the, we got this book is gone. So thank you to those five, uh, patrons who joined us. You've got the book copy coming, some other good stuff coming to you. So, [00:02:00] yeah. Uh, are, are we ready? Are we ready to get this started? Asia? No. You got anything on your mind for the people before we jump in?

Dr. Asia Lyons: No, I'm just ready and excited and I'm looking forward to this interview. And so let's go ahead and roll.

Kevin Adams: Let's go, let's go. So tell us about our guest, who we got. Tell the people who we got.

Dr. Asia Lyons: So we're here with Dr. William A. Smith, who is a professor at the University of Utah, and we brought him on our show today because of his work with racial battle fatigue.

Um, and so he's gonna tell us some of his, the backstory of the research he's done, and make some corrections to some misconceptions that he's heard out here on the web. And, um, hopefully answer some questions for us and our audience members, as well as the folks that we've had who've been interviewed in the past, um, who've experienced racial battle fatigue.

So hopefully you can fill us in on some things. How are you today, Dr. Smith?

Dr. William Smith: I'm doing well. How about you?

Dr. Asia Lyons: No complaints. No complaints. Good. So can you just start us off with, tell us a little bit about yourself?

Dr. William Smith: Sure, [00:03:00] sure. I'm, I'm from Chicago. Um, been at the University of Utah for about, I think this is my 22nd year.

Oh, wow. I've been a professor since 1992. Okay. Um. I did my undergraduate in psychology, my master's in counseling psych, and I focused on social psychology and education, uh, for my doctorate. And that kind of led me eventually to looking at, you know, just human behaviors, uh, stress related illness for, uh, black people.

And then eventually after moving to Salt Lake City is when things kind of came together for me to, um, look at this from a racial battle fatigue lens.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Okay. Awesome. So tell us like, what about Utah? Yes. I see this, like we see the smile on your face. What about you, Tom?

Kevin Adams: We are in Denver, Colorado, so, so we might have an idea of some of the ways that it, uh, yeah.

[00:04:00] Not being in Utah triggered it, but we'd love to hear you. Yeah.

Dr. William Smith: But you know, you know, you are a little bit better than us as black population, but you know, not too much. So, you know, my students at Western Illinois University, when they found out I was leaving to come to Salt Lake, they used to see, they called me brother, professor.

Yeah. And, um, they like, you too black for Utah.

So, you know, the thing that got me was, was, um, you know, when you, when you're in the Midwest, especially in the Chicago land area, it's just flat. Flat, you know? Yep. And if you don't live on a lake, you know, you, you don't have a view of anything. And so when I came here, it was my first time in Salt Lake City, and my wife, uh, told me to be open minded.

Um, and you know, it just blew me away. The mountains were so gorgeous and I always wanted to go to actually Denver. Um, but I came [00:05:00] here first and then we did a trip to Denver. And I love the view of Salt Lake City much more than Denver because the mountains are so far out there. Mm-hmm. And we're like surrounded by mountain views.

Yeah.

na: Yeah. So,

Dr. William Smith: I mean, it's very beautiful. My department was a, a pretty radical department, and so you had people dealing with, uh, anti uh, racist activism. Uh, they were socialists, feminist and everything else, you know? So I kind of felt at home and it was probably the perfect place for me to do the work I do.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Mm-hmm. Yes. Awesome.

Dr. William Smith: Yeah. Yes.

Dr. Asia Lyons: So, um, when we talked to you earlier, you were saying that Wikipedia had your story all wrong and that your work started when you started talking about racial battle fatigue, higher ed with. Um, the educators, the professors in that space, is that correct?

Dr. William Smith: Yeah, that was my first research was on,

Dr. Asia Lyons: um,

Dr. William Smith: black, uh, professors in higher [00:06:00] education.

Um, so black women and men?

Intro: Yes.

Dr. William Smith: And so the first time, the very first time that I presented racial battle fatigue, actually, I think was in Chicago at the, uh, association, American Psychological Association, and, and then a few other places following that. So the first, uh, professional introduction of it was in 2003, although some of the, um, uh, reports out here you see in, in articles of say, 2008, something like that.

But no, it was much earlier and then later I did. Focus on black men and like now I'm doing a folk, I have a national study on black women in racial battle fatigue.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Oh, awesome. So when you first introduced this information and you were talking to folks about it in these conferences, what was the response?

Dr. William Smith: Well, you wouldn't believe it, uh, initially I had a lot of haters out there, so I was, I was getting attacked, [00:07:00] you know? Oh,

Intro: wow.

Dr. William Smith: Yeah. It was all in your head. And, uh, you, you, you just talk about soft people, marshmallows and

Intro: Huh.

Dr. William Smith: You know, things like that and, huh. The word got out because, you know, don't let the PhD fool you.

Yeah. I'm from Chicago, you know, I can hold my own. So Yeah.

Kevin Adams: We don't, we don't about y'all from the shop, we know how y'all roll. Mm-hmm.

Dr. William Smith: I like, I ain't scared to move no furniture.

Kevin Adams: That's right. So,

Dr. William Smith: uh, so, you know, I wasn't gonna be a, a punk, a pushover, nothing like that. So, um, you know, so I, I, I started getting, you know, I kept presenting it and more and more people started showing up that looked like us.

Kevin Adams: Yes. And as

Dr. William Smith: those audiences became darker

Kevin Adams: Yeah. Then,

Dr. William Smith: um, the reception was much better. And, and then to the point that at one conference, I think it was American Educational Research Association meeting, I had a brother who was sitting next to me

Kevin Adams: Yes.

Dr. William Smith: He heard it for the very first time.

Kevin Adams: Yes. [00:08:00]

Dr. William Smith: And he started crying and he was, he was a, a panelist.

Kevin Adams: Mm-hmm.

Dr. William Smith: And 'cause some of the symptoms that I talked about

Intro: Yes.

Dr. William Smith: He started seeing that they related to him and his doctor was misdiagnosing them.

Intro: Hmm.

Dr. William Smith: So now he even had rashes and so he was wondering why he would break out when he would go to work. Uhhuh, he a professor going to historically white campus

Kevin Adams: Yes.

To teach.

Dr. William Smith: And when he would be in faculty meetings and all this stuff, you just break out. And it was because it was so racially, um, uh, insensitive and, and kind of a hostile environment. So, um, you know, the reception got better. Uh, and then it has grown and now it's pretty much international and viral. I just saw something in, uh, um, in the UK that got released and you're starting to see dissertations all over the world and, you know, and publications all over the world in different disciplines.

[00:09:00] So we know. That it's relevant and it's speaking to the pain that people experience.

Kevin Adams: Yeah, no, I love that story because when, when Asia first mentioned the idea of racial battle, battle fatigue, to me, I, I was, I was, because I was like, wait, how have I never heard of this? And I was like, all this is, this is this thing that I'm experiencing and I have, and, and I love that you said like that reaction that people give gave at first, oh, it's in your head.

Are you being soft? 'cause I do that to myself. Oh, don't you know, you gotta, because we're raised a certain way to, you know, accept all this pressure raised in a culture that says, oh, you know, everything's gonna be against you. But then when you're up in it, you're like, is this how it's supposed to be? Is it supposed to be this hard?

This difficult. So you mentioned some of the symptoms, like in your research. Can you just go through for our listeners, what are some of those symptoms that, uh, of racial battle fatigue? So, so when folks can, uh, [00:10:00] uh, we know we have, uh, a problem with, uh, diagnosis in the black community and, and medical treatment, right?

So how can you help us educators better be more informed, uh, on our own, you know, health and wellbeing?

Dr. William Smith: Oh, no problem. So there's basically three major categories. Of, um, racial battle fatigue. So there's the psychological stress responses, they're the emotional behavioral stress responses. Then there's the physiological stress responses.

So let's start with the psychological, and you, you'll probably, if you had a checklist, you'll probably check off many of these. But have you ever been frustrated in these racially insensitive and hostile environments? Probably you have, right? Mm-hmm. Uh, you may have grown defensive, um, towards some of the reactions and responses that you receive.

You could grow, um, apathetic, irritable, um, you can have [00:11:00] sudden changes in mood shock. Like we always seem like we're shocked. So if we're shocked, then that means that we were, um. Not on guard for the potentiality that something might happen like it did.

Kevin Adams: Yep. If

Dr. William Smith: we, if our guards are up, and usually when our guards are up, that's also stressful because we're not supposed to be guarded all the time.

Mm-hmm. So then it can lead to anger, disappointment, resentment, anxiety, worry, uh, disbelief that it even happened. Right. Um, definitely disappointment, um, helplessness, hopelessness, and potentially fear. And I always say that particularly for black faculty, staff, students, and, and even other racially marginalized group, we live between risk and fear.

Risk and fear because we have to navigate and negotiate how we respond, [00:12:00] how we act. Should I speak up on this? Should I say stay silent?

Kevin Adams: Yep. Should I

Dr. William Smith: make a big deal out of a, a big deal situation, or should I just bite my lip? All of that is stressful. So that's, that's the psychological stress responses.

The emotional behavioral ones is, uh, uh, John Henryism, Jane Henryism.

Kevin Adams: Yes.

Dr. William Smith: Stereotype threat. Yep. Uh, it's, uh, uh, maybe increased, uh, commitment to spirituality. Um, how about, uh, imposter syndrome?

Kevin Adams: Yes.

Dr. William Smith: We've all experienced that, right? Mm-hmm. Yeah. It can even lead to procrastination. Um, some of the bad, um, maladaptive responses are increased smoking, increased use of alcohol, swearing.

Um, you might withdraw from people. Right. You might, um, increase your commitment, your spiritual [00:13:00] commitment, or you might withdraw from it.

Kevin Adams: Yep.

Dr. William Smith: Right? So, um, you might have changes within your family dynamics. So all of those are emotional, behavioral ones. Then you have a physiological ones. And those physiological ones are things like headaches.

You might grind your teeth at night. Um, clench jaws, um, chest pain, shortness of breath, muscle aches, rashes as I mentioned earlier. Um, you might have sleep disturbances. Mm-hmm. Um, insomnia. Yep. A frequent illness. Because think about it, if you can't go to bed at night and sleep, recover, rejuvenate rest then.

And if you are on guard during your sleep, like you're on guard during the day, then when does your body have time to recuperate? So really what you're doing is, it's like if you have your fist clenched during the day because of all the things [00:14:00] you have to deal with, and then you go to bed and sleep and your fists are still clenched, you are on guard.

Mm-hmm. So that leads to increased, um, likeliness that you could be sick. So you'll catch colds a lot, right. You might catch, get the flu. Um, you might just feel like you got constant migraines. So all of those are phy, phy, phy physiological responses to racism and the fact that our body is telling us that we're not in a natural environment where we can be fully human.

Intro: Mm-hmm.

Dr. William Smith: So what we have to realize is that, uh, racism is a violent act and the body codes racism as an attack. As a race related attack, a violent act.

Kevin Adams: That's, that's, that's, that's [00:15:00] powerful. You know, when you, when you start to go through all of those symptoms and, and I, I'm just like, God, like you said, it is the checklist.

And, and it, it, it's, it's frightening in a way, you know, because going through this, and I've been teaching for 15 years, I've stuck with it for 15 years, you know, and, and all of those experiences I have had in that 15 years. And, and, and the question becomes, it's like how much. Can I take, is it, what am I doing?

What, what is the ultimate cost to me? Kevin Adams as an educator, you know, to stick this thing out, you know, and, and with the goal of like, when we enter this stuff, you know, I entered at a time where I think it's a belief where it's like, you retire, you, you teach for 30 years, you know, I want to be there for the kids.

I'm halfway through. Um, I, I enjoy what I do. I think, I think I'm good at it, but like I've, I've waited. I'm like, when will this extra stress? Because like, [00:16:00] I'm, you know, coming into it, I heard from white teachers, they're like, oh, year five, year three, you know, it, it becomes oh, so easy. It's so easy. I, I have never felt like it's easy that I don't have to have that, that, that, like you said, risk and fear, right?

Yeah. It's risk. What do I risk for my students? Right? What do I not care about? You know, you teach a lesson. I planned something out and I, I fear what, what is the reaction, right? I just went through having administration pushback on me. Not too bad, but still, you know, really question the motivations of my student and why they were doing something and, and ultimately they were doing something for the good of the community.

And it was pushed back by one parent. And, and it was like, I had to answer for all of this. And I was like, it wasn't a big deal. This, like, this is not where we were going. But, uh, you know, that's my question is, is what are your thoughts about like, being able to stick it out, resisting and, and being able to kind of [00:17:00] maintain throughout all of this, considering everything you've learned about racial battle fatigue?

Dr. William Smith: Well, you, you know, it, we have to realize that we're dealing with it. 'cause if, if we don't realize it, then what we do is we set ourself up for being, like I said. Not on guard, but also in kind of a state of improper alert.

Intro: Hmm. And what

Dr. William Smith: that does is it, it compromises our, um, physiological symptoms, psychological, um, overload, um, and definitely your emotional and behavioral stress will go up.

Let me, let me put it in, in this way. Uh, my mentor is Chester Pierce, was Chester Pierce. He was a psychiatrist at Harvard University. Professor Emeritus died a few years ago in his eighties, and he's the one that gave us racial microaggressions. All right? So [00:18:00] he coined that term. Um, and as I worked through all of these things, um, you know, I, I always would, um, pass it off to him.

Just say, what do you think? And he would say, well, you're, you're on the right track. We need to do this. But Dr. Pierce had this thing called, uh, stem. And it's way before science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. His version of STEM as a, a psychiatrist was this, um, the more your STEM is oppressed, your stress goes up.

Now let me tell you what STEM means. STEM is your space, your time, your energy, and your mobility or your movement. So anytime an oppressive force controls your space, your time, your energy and your mobility, then you are dealing with a stress load. When you have control over those, those areas, space, [00:19:00] time, energy and mobility, then your stress load goes down.

Now we have to control our stem. Now I have something called, um, you know, I look at trauma informed care to racial battle fatigue, and there's three Rs. One of them is realize. All right. We have to realize the systemic and individual nature of racism and how it causes racial battle fatigue. The next R is recognize we have to recognize the signs and symptoms of racial battle fatigue, those things that I enumerated a few minutes ago.

And then we have to respond. That's the next r respond by fully committing to strength-based, asset-based coping strategies. And the last r is this, we have to resist the individual institutional and systemic efforts and racial retraumatization, [00:20:00] right? So allowing the system, the, the, the environment, the oncology to retraumatize us.

So what does that mean? Uh, what's some of the easy things that we can do? Some of the easy things that we can do is make sure your home looks like Asia's home. That, that picture in the background, your picture, uh, Kevin, in your background, you gotta have blackness if you're black people mm-hmm. In your house, you have to control the energy and the, um, the environment because if you have to deal with a hostile climate once you leave your door

Kevin Adams: Yeah.

Dr. William Smith: Because we know that the enemy, the attack, as soon as the black person leaves their house, that's right off. And sometimes with like Breonna Taylor. That's right. You might be in your house, in your bedroom. That's right. Say that

Intro: again. Right?

Dr. William Smith: Yeah. So if the environment, um, feels, uh, comfortable that it, it reinforces your blackness, your culture, um.[00:21:00]

That is one of the most healthy things you can do. And so we have to move away from those things that doesn't, um, repair and restore us. Right. And so, and we have to move away from, uh, allowing, uh, stimuli to come in that threatens our African cosmology.

Kevin Adams: Yes.

Dr. William Smith: Right. And so Joseph Baldwin talks about, um, the kind of African, um, socialization and African cosmology, and those are the things that are always at risk, um, that the television, the radio and the outside, uh, world threatens your blackness.

Kevin Adams: Yes.

Dr. William Smith: So I don't even watch many black movies, black television shows, because it's all propaganda.

Intro: Mm-hmm. Just like it

Dr. William Smith: was with like Harriet Right. All propaganda. Right. And so what it does is it, it it plays on, [00:22:00] uh, people who are unsophisticated who just go in there not with a critical consciousness.

Kevin Adams: Yes.

Dr. William Smith: And that's what Baldwin talk about, the African consciousness is that threat. So the, for right now in the era that we're in is, um, particularly important for black women to watch their, their African consciousness, their mind because of mental side out there. So the attack primarily is on the black woman's mind?

Yes. And the black man's body?

Kevin Adams: Yes. Oh, those

Dr. William Smith: are the two things. Those are the two ingredients needed for genocide.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Can we talk about that? I, two things that nuggets. It, it's a good day, Kevin.

Kevin Adams: It's a brilliant day. It's a brilliant day. This is blessings. Blessings.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Yeah. So wisdom. I need you to go back and talk about that in one moment.

But I, I wanted to say this, that, um, a month or so back, I was talking to a group [00:23:00] about my research and a woman said to me, you know, I couldn't get pregnant as a teacher, as a black woman told me this.

na: Wow.

Dr. Asia Lyons: And until I left teaching and then I could get pregnant. And she said, until you talk about till, I was talking about racial battle fatigue and how it affects the family.

She said, I, I didn't have the word. I didn't know. And it just dawned on her. So I just think about that panel you talked about and like, how many people, like once they know, they can never not know.

na: Right?

Dr. Asia Lyons: Um, so yeah, I just, and I wanted to put that out there to the audience members because. You didn't mention it, and I wanna talk about, like, this idea, and I'm not, obviously, this is not my, like life's work, but infertility.

Mm-hmm. Right? And it makes sense. That's a part of it. It can be. Um, now can we go back to the woman's mind and the man's body, the black man's body and the black woman's mind, um, with this racial battle fatigue and like, how do we like resist? Please. [00:24:00]

Dr. William Smith: Yes. No, no, no problem. What we, what we have to do, and, and I, we have, um, a book that's coming out.

It's, uh, the third edition of the Racial Crisis in American Higher Education. I have a chapter in that that breaks all of these things down. It should be published this summer. But we have to understand that black people are targets of genocide. We're targets of genocide. So, um, some people might hear that and say, well, wait, wait a minute, what do you mean genocide?

Come on. Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm. No genocide. Right? That's, that's something, um. That's right. You know, the indigenous folks here or, or, you know, later on? No, no, no. Um, and actually this is really timely. In 1951, William Patterson took to the un, so that's 70 years ago. Yes. Took to the UN a document, a report that said we charge genocide.

[00:25:00] Yes. And what it was, was a, a complaint on the US government for victims against the Negro people. Now what he did was he looked at what was happening in the short period of time that we call Holocaust, the Holocaust, and the crimes against the Jews there. Yep. Over 400 years of crimes against black people enslavement.

Um. The, the black code period. Jim Crow. And if you understand Michelle Alexander's work Yep. The knew Jim Crow. Yes. Right? Yes. So here's the part that we have to, um, come to terms with the definition of genocide is the whole or part destruction of a group and the mental and physical level. Alright? So who is the most educated in our group?

Black people. Yes. It's the black woman, right? Mm-hmm. Who is the [00:26:00] one that's most targeted with, um, crimes of the state or black man? That's right. So if we look at the killers of unarmed black men, um, again, with the police, 95%, or let's say black people, 95% of the deaths are black men. So we don't know all the names of those black men that die every year.

But it's upwards of 300 and about anywhere from 12 to 15 black women. So the destruction of the body is on the man and the mind of the woman, because she's the one that's breaking glass ceilings. She's the one, uh, that's typically the only black person in high level positions. Mm-hmm. Right. So we have to control that.

And if we can get her off her base and the black man off his base, then it can be a successful genocide. So, like with that movie Harriet, [00:27:00] um, we don't, uh, study Harriet. Most of the things that we know about Harriet was from grade school. Mm-hmm. Because they only allowed, um, uh, elementary books to be published on her.

Yep. There was one book really that I know of, written one biography that was written about Harriet, while Harriet was alive and she talked to her. And that is, uh, Harriet. Moses of her people.

Kevin Adams: Yes.

Dr. William Smith: Right? Yes. And if you read this book, then you'll know that most of that stuff in the movie didn't occur. There was no, there was no black man who was a slave catcher.

How can a black man be a slave catcher? No. Right? What papers are going to get you out of being made a slave to the north and take you back to that. So what sense does that make? But we are so colorable that we are emotional, that we [00:28:00] want to see ourselves and not think critically that. We, what we did was allow them to castigate the black man in that movie.

Mm-hmm. So all the Harriet's pain was black men. Yes. Nothing was about white supremacy. But if you read her book, if you read her book, and there was no love affair, that white slave master didn't love her. Yeah. There was no, he didn't stop a black man from putting a bullet in her head. That's not what Harriet said.

Harriet said the opposite. He was brutal. And she said that, um, she got beat severely, almost like skin coming off of her from a white woman who, who made her stay up all night to, um, uh, make sure her baby, the white woman's baby, didn't wake her. Hmm. And if the baby cried, Harriet would get beat if, and then Harriet was supposed to [00:29:00] clean the house.

She was just a little girl. She didn't know how to clean the house. The woman would severely beat her and it was the white woman's sister who came down and then said, well, how are you? How does she know how to clean if you never teach it? All right. So the thing is, what I'm suggesting only is this, is that Harriet, herself, queen Mother Harriet, tells us about white supremacy and tells us all the things that occurred.

Why would Hollywood do what they did and make up? You can't gimme creative license and make up all of those situations so they can control the mind. That's right. And, and make it easier to see us in a less than position. So that's the mental side that we keep watching on TV and in movies because we don't think critically.

So we have to really, um, watch what we consume because what we are consuming is [00:30:00] poison. Huh? Hmm. This, this is her book is less than a hundred pages. Yep. Yep.

Dr. Asia Lyons: It, it say the book, the book title again for our audience, please. It's

Dr. William Smith: written by Sarah Hopkins Bradford. The book is Harriet, the Moses of her people, a biography of Harriet Tubman.

She was alive when the biography was being written and was being interviewed by Bradford.

Kevin Adams: And that's the interesting thing Dr. Smith right now is, is we see, and I think we see it with Dr. King, with all of these movies that come out, is there's a revamping of the story. Yeah. Like the story is being told in a different way.

And, and, and I, I love this point about critical thinking, and I think it ties back to your point about the role of resistance, right. As educators. And when I think about my role as an educator, it's, it's, a big part of it is, is [00:31:00] teaching kids to think critically about the world around them, about the situations they find themselves in.

Yeah.

Intro: You know, and,

Kevin Adams: and I teach sixth grade right now. And, and it's amazing how much white supremacy that the kids have already internalized about the way the world works and, and, and, uh, relationships and why people are in certain situations, you know? Um, and so it really is fascinating and to think about Harriet's example of, of who she really was versus who they wanna tell us she was.

Mm-hmm. Right. I I think that's really powerful.

Dr. William Smith: Yeah. You know, you know that old saying, if you want to keep information from black people Yep.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Hiding in a book.

Dr. William Smith: Put in a book, we can be, um, easy victims, easy prey. We know we've had study group book clubs since the twenties. We have to bring them back and have discussions.

Uh, we need to read books like ku Yes. From [00:32:00] Ani. Yes. Right. So you can't read it by yourself. 'cause you know, that's heavy, heavy. You gotta be in discussion groups. Break that stuff down. We need to read the, um, autobiography of Asada. Shaku. Yes. Right. So we can understand, um, what our plight is, what the historical, um, situations were and how are they changed today.

Remember what they said, J Edgar Hoover said, what do not allow the rising of a black Messiah. Messiah. That's right. Right. And so every time, what did he do when he had black, um, groups? He would kill the head. He, he shot King, he shot Malcolm. He shot Fed Hampton. Mm-hmm. All these people, right Now, if they're millionaires a day, then we have to kind of look at them a little differently, right?

Yep. You know, because Revolu like, uh, Kwame Turre say revenue revolutionaries aren't a millionaires.

Kevin Adams: They are, [00:33:00]

Dr. Asia Lyons: you know, this, that, it's interesting. So I, I think about that. And I wanna switch this over to say like, how many revolutionaries are administrators?

Dr. William Smith: You don't

Dr. Asia Lyons: how many how I, I, I really, I pushed upon this idea of, um, black educators, um, bipoc educators and administrative positions, superintendents and super assistant superintendency higher places.

And ha like, have you not experienced or turned an eye to the racial battle fatigue of other black educators this whole time? We just kept, like, moving up the ranks. Mm-hmm. Like, how does that work? Right? Mm-hmm. I think about that and I think about if you, is it this like, okay, when I get more power, then I'm gonna say something.

Kevin Adams: Mm-hmm.

Dr. Asia Lyons: When I, when I, when when I get this next position, then I'm gonna speak up. And meanwhile, once I'm

Kevin Adams: superintendent everything, I'm gonna change it [00:34:00] all. Yeah.

Dr. Asia Lyons: When I become superintendent, I'm gonna change it all. And meanwhile, black folks. Educators are fleeing education for their lives while waiting for someone to get some more power.

Right? So the same thing about the being a millionaire, same thing with positions of power education.

Dr. William Smith: Mm-hmm.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Mm-hmm. Right. That's why I see it.

Dr. William Smith: Yeah, no, you, you're right. And see, not too many administrators are revolutionary, but administrators can do revolutionary work. Mm-hmm. Just like teachers can do revolutionary work because they control the, the, the development of the minds.

So you can teach off of the curriculum. You know, they say that hidden curriculum, so you need to take ownership of that and make a hidden curriculum. What happened in the sixties and the seventies, you know, when you, if you were born and you were in school, then these, and in black communities, what. You were being taught was kind of black power and [00:35:00] black pride.

Yes. And that is what the system feared. And so they had to destroy that. So they know education is a, a, a valuable tool to lead to the liberation of black people. So we have to control it. Remember the minds, everything that we do has to run through a litmus test. How does it impact the mind and bodies of black people and critically think about, um, as I've coined other terms, anti-black misogyny, anti-black misandry.

What about those things? Um. Promote the hatred, the, the, the, um, destruction, the invisibility of black women. What about those things do the same for black men?

Intro: Mm-hmm.

Dr. William Smith: So we have to get off of, uh, oppression, sweep states and say, we are family. I don't care if you are poor, rich, [00:36:00] gay, straight, trans, um, you have ability, issues, whatever it is with family.

So if I allow you somebody to attack a member of my family, yes. I have no power.

Kevin Adams: That's right.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

Kevin Adams: That's right.

Dr. Asia Lyons: I love that. I love that.

Kevin Adams: No, I think, I think it's so important, just, just when I think about. The movement, you know, uh, for black liberation is it's gotta be all of us. It, it can't be turning us against each other.

It becomes the easy, you know, and that's what I think when, when I hear you talking about genocide is also that's rooted in there, is turning us against each other, you know? Um, and, and so, you know, looking back on everything you've talked about and thinking about, um, racial battle fatigue, you know, like the, the question is can [00:37:00] we, can we hope to use, and, and you said education can be powerful, but is, are we, are we as teachers.

Are we justified in looking? And I, I don't know if it's justified, but are we looking in the right place? If we look to, for education as a means of black liberation? Is education still? Because I think for a long time it was, you know, a space of it. But I just think about the attack on schools. Um, black teachers in particular, even though they say they want us anytime, I think we move in that direction.

Where we are, are pro-black, uh, we uplift our students, our BIPOC students, we, we, we support LGBTQ plus, you know, students and community members. We try to build intersectional movements. I feel like that's constantly attacked. Right. And, and, and more so in our city, we have a lot of charter schools and schools that, uh, don't make the cut and get taken over.

And so, and it feels like those are often schools that are trying to do. [00:38:00] The things that we are talking about that are needed Right. To, to and, and, and they're the schools that are more harshly judged for their test scores. Teachers get lower ratings. Um, so what are your thoughts about how all of that type of stuff plays out?

Dr. William Smith: Yeah. We, we have to control our education and, and we have to again, learn from history, right? So one of the things is we need to have more black independent schools again. Yes. Uh, we need to support them. We have the money. Don't believe that, um, black folks can't, uh, pay for things. Uh, we have the economic ability within our group to basically control our whole destiny.

Mm-hmm. Um, so we have to realize and, and believe in ourself. What, what has happened now is when I said that attack is on the mind and the body now. The major attack is on the black woman's mind and the major attack is on the black man's body. But the black man's mind is being [00:39:00] attacked too. Mm-hmm. And the black woman's body is being attacked.

Yes. Mm-hmm. As well.

Intro: Mm-hmm.

Dr. William Smith: So what we have to realize is what is education? You remember, um, in wmu Soldier had a, a book called Too Much School and too Little Education.

na: Mm-hmm.

Dr. William Smith: Right? So we don't wanna be school, we wanna be educated. Mm-hmm. Right? So that could be, um, after school programs. Mm. Right. If you belong to your a black church or something like that.

Alright. Let's have something that educates them on critical thinking skills. The kids in the school, we have to take more control. See what's happening is the black community is not only dealing with, uh, racial battle fatigue, but one of the levels of racial battle fatigue that they're dealing with is cultural.

Um, depression. Yes.

Intro: Right.

Dr. William Smith: So cultural depression. You want to, I'm just too tired. Uh, I, I want to give up. Uh, I don't have the energy, uh, I, uh, just leave me [00:40:00] alone. I don't want to do that fight. But what that means is you need therapy, cultural therapy.

Intro: So

Dr. William Smith: you need help to make sure that you can keep your head above water enough to fight your enemy.

And we have to understand who is our enemy? Anybody that tries to attack the black body. Yes. And the black mind. Right. So that means that we can't allow, we have to draw from the culture that we once, uh, had. Mm-hmm. And African consciousness and culture that has been attacked since the sixties. Alright, so now what?

The culture that many of us. Think its black culture is created by Hollywood. Yes,

Kevin Adams: for

Intro: sure.

Kevin Adams: Right. It could be bought and sold.

Dr. William Smith: It

Kevin Adams: could be

Intro: bought and sold. Sure.

Dr. William Smith: Vicki Minaj is black culture.

na: Mm-hmm.

Dr. William Smith: Now some people could say that. Yeah. Well, there was sisters [00:41:00] dancing like that in Africa, but they had spiritual principles.

That's right. The cultural reasons why they danced a certain way and we weren't looking at it in the, uh, uh, uh, uh, as a sexual marketplace.

Kevin Adams: Yes.

Dr. William Smith: Right. So don't try to confuse, um, your, your, your, you know, distorted, uh, way expression of our culture with high culture of Africa. Right. And even the high culture.

I mean, think about this, um, uh, there's a book, um, Leroy Jones, um, um, now I'm, I'm forgetting the name that he, um. He changed his name to, but it was Blues People was the book. And he, in that book, um, he said that once African stopped singing, um, songs, uh, in their culture and in that language from that culture and that language and started singing the blues and jazz and stuff, we [00:42:00] became African Americans.

Yes. Right? Mm-hmm. So we have to reach back. Now, there's nothing wrong with being African American. Yes. Because there's some deep culture there. Because we, we built Tulsa that's built Rosewood. We built, um, Bronzeville in Chicago. That's right. White supremacy attacked it. We have to be smarter than our oppressors, but we have to go back and have that, um, belief in self and that, and develop that African consciousness.

And that's what education is about. If you're not teaching to enlighten and, and, and, and liberate and, and protect the mind and also the body. Now we have to become healthy because, um, our attack is at a physiological level all around. Yeah. And a mental level. Right? So that means that if we going to fight white supremacy, we gotta be in shape.

Mm-hmm. That's right. But we, we have to make a pledge. Now. We know that, um, the cortisol flood that, [00:43:00] that we get from having to be stressed out all the time also impacts our weight. Either we those too much or we gain a whole bunch, but it doesn't explain the whole variance of why black folks are overweight.

So that means that we gotta eat better, we gotta meditate, we gotta make sure our environment smell like collard greens and, and you know, we gotta have, uh, we don't, you know what, I didn't even know what Pop Puri Potpourri was. I was calling it pot pur when I went to college, right? Yep, yep. I didn't know how to spell it.

That's right. And white people would say, no, it's potpourri. I what

Intro: the

Dr. William Smith: heck? It's potpourri. And they said, you put in a, a little bowl with all these flour dried flo. I said, no, no, no. We got collard green in the house. We got black eyed peas.

Kevin Adams: Peas. That's right.

Dr. William Smith: We fried chicken down. We can't have too much fried chicken.

But it still smell good, right? It still does. So the thing is, we didn't have to have all them fake smells because we had stuff that nourished the body. [00:44:00] But here's the point. Big mama used to cook in a way that was healthy because there were certain herbs and different things she would put in the food.

Um, lost track of, because now people brag, oh, I don't cook. I don't know how to cook. And they feel good about that. No, no, no. We have to remember that Those were like medicine women. Sure. So now we, we've taken away the things that, um, black women, um, were known for and was had, um, you know, it was a strong part of our culture because it kept us healthy.

I mean, uh, we had to have Castral Oil around this time, you know, just telling my, my youngest son, we used to move all the furniture out of the house to do spring cleaning.

Kevin Adams: That's

Dr. William Smith: right. That's right. You clean it up, right? And then you move it back. Now the, and we might not be able to do that nowadays, but we can't divorce [00:45:00] ourselves from those things and traditions that protected us for 400 years.

Now I'm not talking about eating. Uh, uh, uh, um, uh, what's the stuff out the pigs? Uh, chitlins. Chitlins. I ain't talking. Chis, right?

Kevin Adams: You can put that away.

Dr. William Smith: Can put that

Kevin Adams: away.

Dr. William Smith: But I'm talking about the healthy things that Big Mama. Um. Would make us take and eat. That's right. Right? That's right. And if we would be healthy

Kevin Adams: creams out the yard and, and that we, now we know those dark leafy greens are probably some of the best things that you could be eating.

Yeah, exactly. Right, right.

Dr. Asia Lyons: I think, I think it's really, I'm glad that you're seeing this. It's really important that we talk about, we hear about the, the healing and the food and the mindset and the reading. Right. As all of this is a way to resist, right. Because we could get into a space where folks say, I wanna do massage.

I'm gonna do all the things that some of them are cost money and folks [00:46:00] can't afford.

Kevin Adams: Yep.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Yep. Right. Um, and so we have to be like, we have to recognize like Yeah. Eating healthy foods, putting good things into our body and sleep and all these things and, and building schools where the teacher belongs.

na: Yep.

And

Dr. Asia Lyons: the student belongs are all part of that healing. Right. Right. I, I love that we're talking about that because that's really, really important that we, we had to recognize it. We have to, um, because if we don't, we're gonna continue to see folks again flee. Like fleeing our schools, fleeing, leaving our black and brown students behind, unfortunately, uh, dying early, right?

Mm-hmm. From the stress, from the shock, from the grief or things like that. So I'm glad they were talking about this.

Dr. William Smith: Yeah. 'cause you know, black men are. Even though the, the, uh, mortality rates are, the gap is closing. Yes. Black men are still 25 to 35 years behind black women, white women and white men. [00:47:00] So when you look at it, it's a 25 to 35 year gap.

Right. And so we have to understand what is going on about that. And the fact is, uh, even though I know all this stuff, I wasn't doing the sleeping thing like I should have done. Yep. Until this, uh, uh, pandemic. And I've fallen in love with getting my sleep now. And guess what happened? Um, the, the, my, uh, memory has been the sharpest it's ever been.

My recall has been the sharpest it's ever been because I got the appropriate amount of sleep. And we don't realize that 'cause we are taxing our bodies. And so you'd be like, I can't remember what I was doing. I can't remember where I placed it. I can't recall that study. You know? And it's because our body is tired and we just keep on running and you'll drink coffee and them, them little, them drinks that, uh, rock stars and all that stuff.

And, and let me, let me give [00:48:00] you uh, some data on this on black women. Um, there was a study that said that black women who face daily, um, racism had like a 2.7 odds of having lower cognitive function than those women who don't. The other thing is black women who are experiencing in, uh, institutionalized racism almost had, were at three times more risk of lower subjective, um, cognitive functioning.

What does that mean? Memory loss? Alzheimer. And which is diagnosed because, misdiagnosed, I should say because it's part of the res racial battle fatigue response. But they say, oh, oh, mama got, um, Alzheimer's. Alzheimer's. Well, how did she get it? Right? That's right. So, and we keep looking at the outcome and not what happened to lead to it.

And we're misdiagnosing it because [00:49:00] racism plays a heavy part in even, um, cognitive functioning. We have to protect that. And there's other studies that have shown that for black women, that black women who were stressed with racism. That's right. Gender racism as teenagers, by the time they get to their forties and fifties, if their children who are adolescents experienced racism, that they have a, um, more likely to face depression and all other types of things.

And guess what? Now that, um, isn't the case for black men. But black men, if their children are stressed and their wife is stressed, then they're stressed.

Kevin Adams: They're the stress for them.

Dr. William Smith: They already have their own cumulative stress, but then they take the stress load of the wife and the children. Now guess what happens with that is a vicious circle.

When the black father is stressed, the children feel it.

Kevin Adams: Yep,

Dr. William Smith: sure. And then they [00:50:00] become more stressed and more likely to have early onset of depression. Mm. It's a vicious cycle. Dang. Right. So, so people can't get away from it. Now the mother doesn't feel as stressed about the father, but she is concerned.

Yeah. But she doesn't take, there's, there's been no positive correlation there, but it shows a vicious circle.

Intro: Sure. Wow.

Dr. William Smith: And that's how racial battle fatigue kind of works in ways in which we haven't fully understood it before. 'cause we didn't have the language and the ability to spotlight it.

Kevin Adams: It's just fa it, it is fascinating. It, yeah. I mean, because when you describe it all, especially that, that kind of circular relationship of it all, it's stuff I've experienced in my own house and my own family and watched it, you know, happen and, and it, it's just very. Interesting how that plays out, um, [00:51:00] as you go through these experiences and, and this, this deeper idea that it impacts more more than just like the individual, right.

That it's, it's bigger, it's, it, it think this goes to Asia's research. Mm-hmm. Is it, it impacts the whole family, friends, you know, everybody. Yeah. And I just wanna go back to this point where you talked about that cultural depression, because I'm a member of the Black Educator Caucus and, and so it is doing extra work organizing.

Right. But um, and I go into it tired, you know, and I'm like, wow, dang, I do this extra stuff, you know? And, and, but I always come away feeling better. Right? And so it reminds me of those, those circles, those times where we come together. Like I think when you go back to like coming back to our African consciousness, it's communal and it's nature.

Right? Right. And so coming together and I. In a way, you know, our community has been really impacted by the pandemic because it, it goes against our nature, which is [00:52:00] to say, Hey, we all in this together. We are communal. I got you. Let's come together. And, and in a lot of ways, the very thing that helps us, harms us in this pandemic situation.

Yeah. Right? Yeah. Because we don't have equitable. Uh, care. So I, I just really, that hit me big. But also you mentioned thinking about, and Asia, your point to administrators, like what would you advise? How, so we have some administrators who listen to our show. What would you recommend for administrator? How should administrators, both bipoc administrators, but also white administrators, how can they help to reduce racial battle fatigue?

Because I know they can't, you know, because it is big, it's systematic, it's institutional. But what are some policies that a school, and I'm a part of our equity team 'cause I'm a black dude, so anything that happens with equity, I got to be there. Like, you know, of course. Because, 'cause if I'm not there, I don't know what they might do.

Right. Right. And then if I'm not there, they're gonna tap me. But [00:53:00] what, what are some things that we can do to, to just help to counteract the racial battle fatigue in educational institutions?

Dr. William Smith: Well, one of the things we have to do is, um, as much as possible. Limit our use of the term bipoc. Oh, all right. Oh,

Kevin Adams: talk about that.

Dr. William Smith: Well, first of all, I, under, as I understand it, the origins of it comes outta Canada, and that's because the POC, um, always kind of marginalized black and indigenous people. So that's my understanding from, uh, where it comes from. Not that that's bad. Yep. But what it does is we have to disaggregate our groups.

We cannot continue to put ourself into a collective like that, because then what happens is whoever does the best, skews the information for the [00:54:00] people who are in most need.

Kevin Adams: Yes.

Dr. William Smith: And so right now black people are in tremendous need and in indigenous people too. All, all these racialized groups are who I call targets of white supremacy.

na: Yes.

Dr. William Smith: So all these targets are in tremendous need, but at the very bottom of almost every social demographic factor that we see is black people and indigenous people. Mm-hmm. But black people. Okay. And so what do we have to do? We have to disaggregate black people as well. Hmm. So we need to know what cisgender black women are experiencing.

Um, black, uh, gay women are experiencing black trans women are experiencing black women with a disability. Experiencing. So once we get at the, that finite level, right? Then we can start making claims about what is needed for each particular group. Mm-hmm. As long as we put 'em all together, then what [00:55:00] happens is we will not get the, um, attention that we deserve.

So we, we have to start to disa aggregate groups. And let me put it this way, um, when, uh, when you are in college, if, if the school, your university said that, um, uh, we did a campus climate survey and the results come back from all the students and say, it's a very warm and welcoming climate, your first critique would, would be, well, what students?

Intro: Right? Right.

Dr. William Smith: Yep. And then they would say, well, all students. He said, no, no, no. You gotta break that down for us. We need to know about race. Right? Yep. And so you would be right to ask them that. So now let's think about Latinx as a group. Who does it benefit and who does it hurt?

Intro: Mm-hmm.

Dr. William Smith: So we don't know what the intention that Puerto Ricans might need.

Intro: Mm-hmm.

Dr. William Smith: Uh, we don't know what Guatemalans might need. That's right. We don't know what Hondu hon Honduran Americans [00:56:00] might need, you know, because the biggest group is Mexican American, right? Yeah. And so we need to just aggregate all those group Asian Americans the same way. Yeah. Right? Because it is really, they, we talk about it as racist when you aggregate.

So why do we keep perpetuating that? So we want to know, uh, the dropout rates by certain groups disaggregated. So we have to do very, we have to do better than that now for administrators. Um, what we need is for them just to quit being so racist. One, uh, well,

there it is.

Dr. William Smith: There it is. There it is. There.

Go right there.

Dr. William Smith: And two, even if it, we look at Derek Bell's concept of interest convergence. Yes. They benefit more by having black folks in the schools. That's right. Uh, as teachers, as administrators, as staff, and as students, right. That's right. So [00:57:00] here's the thing. Um, we know that, so that means that we bring a resource.

To the schools that people drain from us and we don't get anything hardly in return.

Kevin Adams: That's right.

Dr. William Smith: Right. But what we've also learned from studies, um, Goldsmith has a study out that looked at black teachers, um, and black teachers was black, um, white students, um, Latino and white students. And what they found was, um, that when they had black teachers, their critical thinking skills went up, their critical consciousness went up, um, their scores went up.

But when they had white teachers, the black and brown students suffered. Hmm. Right. So that what that tell you that there's something that black teachers bring that other teachers don't have, particularly white, uh, teachers. Teachers, well, oh, let me say [00:58:00] this. The white students benefited too and better grades.

Kevin Adams: Yep, yep. Yep. Than,

Dr. William Smith: than they did with just a white teacher. So there's something language, there's something, um, about what you are as a human being and your, um, experiences that you are a master teacher that's being under and underappreciated and under recognized.

Intro: Hmm hmm.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Yeah. Yeah. Powerful. Powerful. It is powerful.

And that word drain.

Kevin Adams: Yes.

Dr. Asia Lyons: That's, that's the feeling when I taught was drained. And it's interesting, just recently I started to tell people when they say, well, how long did you teach? Well, I was in education for 12 years and 10 of those years I up uplifted white supremacy culture.

na: Mm-hmm. Yeah. I mean,

Dr. Asia Lyons: went into those last two years.

Where I started to [00:59:00] speak up and do the things you spoke about is then I bega, I began to feel that drain and I began to be pushed out.

Kevin Adams: Yep,

Dr. William Smith: yep.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Yeah. So that yeah, that's so, that's so interesting.

Dr. William Smith: Yeah. What we have to do is, black folks is make, um, these profess these, um, professions are are night jobs. And yes, the liberation, our people are day jobs.

Day jobs. In fact, that finances your liberation. Right. So you take the resources that you can from your collective education and experiences and let somebody, um, pay you for those resources, and then you use that as an opportunity to provide for your people. So, um, yeah, I, I'm a professor. I, I'm well paid.

Um, I'm well recognized.

na: Mm-hmm.

Dr. William Smith: That's my, that's my night job. That's right. My day job is everything I do. I mean, I got the, [01:00:00] uh, what was it? Spencer Foundation's Mentor of the Year award. Right. That's 'cause I'm helping black people.

Kevin Adams: That's right.

Dr. William Smith: Right. I'm helping, um, young black professors, um, to get tenure and promoted, right?

Yes. I'm helping graduate students. So my goal is the liberation and the, the edification of our people.

Kevin Adams: That that's what that mean. What that, when you talk about that again. African consciousness, what African education traditionally was. It was more of that one-on-one. Those are the most powerful people.

The people who brought me aside, put my arm, put their arm around me, let me understand where, like, where I was, was okay. You know, that I was gonna be somebody I had, you know, a destiny because I was important and I came from important people, right? Mm-hmm. And I think that's, that's where it goes back to.

Um, I think when it, when we, you talking about resisting, you know, [01:01:00] resisting, uh, the racial battle fatigue and, and just. And just, I don't know. It's just powerful stuff. It's stuff that I'm, you know, I, I'm at the end of spring break. I'll, I'll be honest, I wanna, I'm like, can I, can I not go back the last two months?

Can I not? Because that's how I, I'm, you know, like in the end, like, I'm like the Bernie Mac joke. 'cause like, I go on break, I go on break, right. I'm sitting at my desk, I, I'm gonna break. I, I'll be back when I'm, I'm gonna break break. Fred Max. Yeah.

Dr. William Smith: Well see. You gotta, you gotta shift, um, that cognitive reality and make that your night job.

Kevin Adams: Yes.

Dr. William Smith: Help the stu all students now we, we, we gonna help everybody anyway. That's

Kevin Adams: right. That's right. But we don't

Dr. William Smith: help all the students, but make like this your podcast and other things that helps for the liberation of our people. What we have to remember is, um, we got misled with the concept of church.

Kevin Adams: Mm-hmm.

Dr. William Smith: Church [01:02:00] talks about a broken body of

Kevin Adams: people. Yes.

Dr. William Smith: Right. Well, it primarily focuses on, on Jesus, but heru in K commit Egypt was also a broken body that had to be put back together. Right. So what church really represents what you were talking about, about, um, this pandemic and the need for black people to be together.

Yes. This is part of the broken body. So people, um, kind of misunderstand the purpose of church or organization. It's about the energy and the power of the collective coming together for a common goal. Right. So what we need is more organizations. That's what Kwame Tore used to always say. The problem with black people is that we lack, or, and he used to use his little accent organization, right.

He said, we always had a plan for the march. We [01:03:00] didn't have a plan for the day after the march.

Intro: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

Dr. William Smith: And so what we have to do as a collective is remember to have to join organizations of like-minded people with like-minded goals. And then, uh, enjoy that opportunity of coming together for a common good.

Right. Because that is the, um, body of haru coming back together, or as a Christian would say, the body of Christ. Yes. Coming together.

Kevin Adams: That's it. That's it.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Yeah. Well, Dr. Smith, um, I hate to end this.

Dr. William Smith: No problem. No problem.

Dr. Asia Lyons: And we'll be here all night just getting the jewels, the gems. I have written down stem, I've written down so much information. I hope that our audience can hear this.

Kevin Adams: Book recommendations, [01:04:00] all of it. Like, I, I mean, it, it is all this is a good one.

This is, I mean, I, and I think it's important because we've been talking about racial battle fatigue, but I think this gives a real solid context for, you know, um, this podcast and, and just, I think the importance of the work that, uh, you've done Dr. Smith and the work Asia that you are engaging in and all the work, I think it's more powerful.

And I love this idea that people were like, oh, that's not real. And then they start to see it. Because I think that's how it always is, is is that people are like, oh, you're making this up. Right? They're like, I'm not making, this is, this is my lived experience. If you let me study it intellectually and, and you allow me to take it where it goes

Intro: mm-hmm.

Kevin Adams: You're gonna discover some things that are, I think are important to, you know, this institution of education that is, you know, in need of more black educators. And as you pointed out, Dr. Smith, all kids mm-hmm. Benefit. From having black educators, all kids. It's [01:05:00] better to have black teachers and your school than not.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Right. Yeah. And not draining them by the way, and not

Kevin Adams: draining them.

Dr. William Smith: You gotta support 'em. Give 'em the resources and, you know, recognize them and their kind of community cultural wealth that they bring.

Kevin Adams: Yes.

Dr. Asia Lyons: All right, well we gonna have to wrap up this episode, episode five of the, 'cause we gonna be all night out here with these.

I'll come back.

Dr. William Smith: I'll, I'll come back when you invite. Yes.

Dr. Asia Lyons: We'll we will be inviting you back for sure. Um, 'cause we still didn't have any chance to really talk about some of the stories that we've heard, and we'd love to hear, um, your opinions and thoughts and ideas about some of the folks that have come across, um, our podcast so far.

Um, but yeah, just thank you so much for coming and speaking to us, for, to our audience, we just, we really appreciate your research and your work. Um, just thank you so much.

Dr. William Smith: Yes.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Yeah.

Dr. William Smith: I'm, I'm, I'm happy to be [01:06:00] here

Dr. Asia Lyons: five of the exit interview. We'll see you all next time. All

Intro: I.

Chief Executive Administrator at Huntsman Mental Health Institute (formerly University Neuropsychiatric Institute)

Dr. Smith is the Chief Executive Administrator for Justice, Equity, Diversity, & Inclusion (JEDI) in the Huntsman Mental Health Institute, Department of Psychiatry, in the School of Medicine. He is also a Full Professor & former Department Chair with a demonstrated history of working in the higher education, community-based, private, and professional industries. The developer of the biopsychosocial framework of Racial Battle Fatigue. He is skilled in Nonprofit Organizations, Sociology of Education, Critical Race Theory, Program Evaluation, and Academic Advising. Strong professional with a Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) focused in Educational Policy, Social Psychology of Education, and Educational Sociology from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.