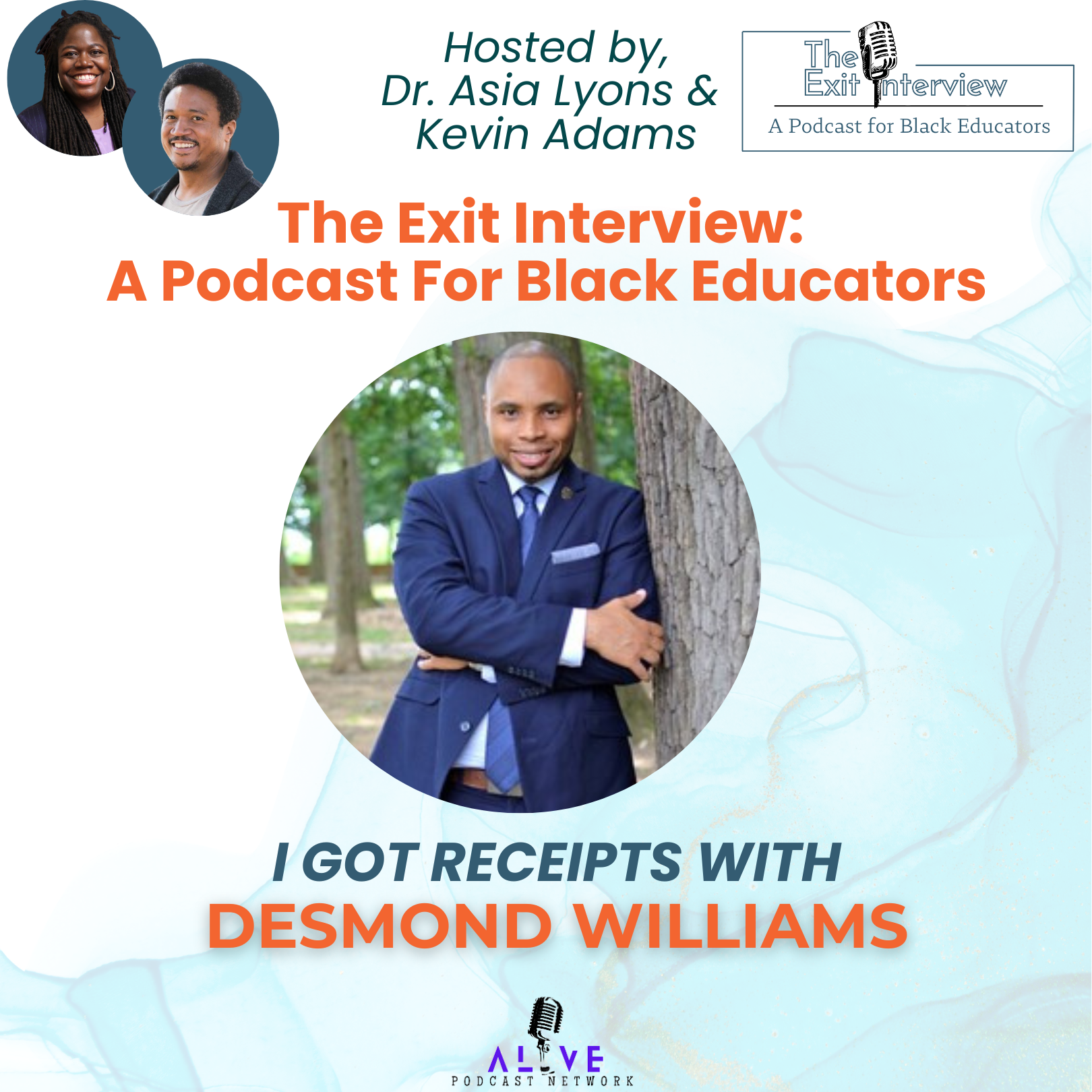

I Got Receipts with Desmond Williams

Scholar, Author, Entrepreneur, and Educator Desmond Williams has been there, done that. A talented and effective classroom teacher, he quickly moved up the ranks to become a building leader. But even as a principal, Desmond was not achieving the impact he wanted to. He found himself in frequent conflict with fellow leaders and gained clarity.

That sense of clarity has manifested in his DEI firm Nylinka, a book, The Burning House, in which he echoes Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s question about racism as a system that perhaps African Americans should try to escape, and frequent speaking engagements and training. Desmond shares his story, questions the notion of Racial Battle Fatigue, and gets out the receipts. Do not miss this one!

Show Notes: "I Got Receipts with Desmond Williams"

Episode Overview: In this episode, hosts Dr. Asia Lyon and Kevin Adams sit down with Desmond Williams, an experienced educator, administrator, and founder of Lanka School Solutions. Desmond shares his journey through education, from teaching and administration to consulting, and reflects on the challenges and triumphs of working in schools serving marginalized communities.

Key Topics Discussed:

- Desmond’s path from special education teacher to administrator and consultant

- The financial realities and pressures that influence career moves in education

- The unique challenges and opportunities for Black male educators and administrators

- Racial battle fatigue: what it means, how it manifests, and how Desmond navigated it

- The importance of representation and leadership in schools serving Black and Brown students

- The impact of systemic racism in education and the need for liberatory schooling

- Desmond’s work with Lanka School Solutions, focusing on supporting marginalized students and professional development for educators

- The vision for a national union for Black male educators

- Reflections on the legacy of Black educators and the effects of desegregation

Notable Quotes:

- “You have to remain responsible for yourself. If you make decisions only for others, you won’t make the decision that’s best for you.”

- “America is a sexist country. Even though 80% of K-12 educators are women, over half of administrators are men.”

- “The genius of white supremacy as a system is that it doesn’t need white people in place for it to run efficiently.”

- “We have to create a world without white supremacy by educating our children and our people.”

Resources & Links:

- Lanka School Solutions: nyka.org

- Desmond Williams on social media: @ilanka (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter), LinkedIn: Desmond Williams

- Book: "The Burning House: Educating Black Boys in Modern America" (available for pre-order on the website and Amazon)

- Patreon: Support the podcast at patreon.com/twodopeteachers

Special Thanks:

- Shout out to Dr. Antoine Jefferson and Dr. Leslie Fenwick for their work on Black education and unions

- Thanks to all listeners and supporters who help keep the conversation going

Contact & Follow:

- For consulting, workshops, or to connect with Desmond, visit his website or reach out on social media.

Closing Thoughts: This episode is a powerful exploration of the intersections of race, leadership, and education. Desmond’s candid reflections offer valuable insights for educators, administrators, and anyone interested in educational justice.

First of all.... have you signed up for our newsletter, Black Educators, Be Well? Why wait?

Amidst all the conversations about recruiting Black educators, where are the discussions about retention? The Exit Interview podcast was created to elevate the stories of Black educators who have been pushed out of the classroom and central office while experiencing racism-related stress and racial battle fatigue.

The Exit Interview Podcast is for current and former Black educators. It is also for school districts, teachers' unions, families, and others interested in better understanding the challenges of retaining Black people in education.

Please enjoy the episode.

Peace out,

Dr. Asia Lyons

I Got Receipts with Desmond Williams

Gerardo: [00:00:00] I wanna tell you about one of our partners, tz All Education Consulting, tz, all Education Consulting, is a queer, black and indigenous women owned firm. Offering anti-racist consulting, pd, coaching keynotes, workshops, and more. Their newly released abolitionist teaching workshop series coaches and prepares teachers to further develop abolitionist practices in the classroom.

Find out why they have been called The Future of Educational Justice by Dr. Bettina Love. You can book a free consultation with TZ by calling 5 1 0 3 9 7 8 0 1 1 or visiting tz ec.com. That is Q-U-E-T-Z-A-L-E c.com. And if you mention you heard about them through two dope teachers, you will receive a 5% discount on their abolitionist teaching PD series.

Once again, you can book them by visiting gaal [00:01:00] ec.com on their Connect with Us page.

Kevin Adams: Hello, welcome to the exit interview. I'm here with the preeminent Asia lines.

Dr. Asia Lyon: Hey everybody. How's it going?

Kevin Adams: We are doing good. And I am Kevin Adams, the co-host of the Exit interview, and we have a amazing interview for the people tonight. Asia, do you wanna tell the people about our guest?

Dr. Asia Lyon: So we're, um, interviewing Desmond Williams today.

Um, and Desmond's been on two dope teachers already, so he has come already vetted. Amazing. And he's back to share his story about, um, his [00:02:00] work in schools as a principal, as an educator, uh, in the classroom. Um, some of his reflections around racial battle fatigue and also what he's doing now with, uh, his organization, Lanka.

So yeah, we're just gonna listen to his stories. And always a pleasure to talk to someone from Detroit as a fellow. Detroiter. That's right. Represent

Kevin Adams: the D all day. All day,

Dr. Asia Lyon: all day. That made me happy. But yeah. So

Kevin Adams: Asia, hold on. Before we get into the interview, I tell you, one of my friends, he told me, Detroit is known as midnight.

Have you ever heard this?

Dr. Asia Lyon: No, I have not.

Kevin Adams: And so here's what he told me. He said it was midnight because on the Underground Railroad, if you made it to Detroit, you were considered at midnight. And if you made it across the border to Canada, it was dawn. So, I don't know if this is true, but that's what I heard, that Detroit is known as midnight

Dr. Asia Lyon: maybe to you, to your friend.

It is,

Kevin Adams: I guess so. I've never heard [00:03:00] this story, so I, I gotta do research, exit interview people, do some research, get in your Googles, let us know if that is is the case or, or, or is my boy, as we say, CAPP.

Dr. Asia Lyon: Yeah, he prob he probably captain.

Kevin Adams: He probably be captain.

Dr. Asia Lyon: Yeah. He white.

Kevin Adams: So, so we never know. You know how these white boys get,

Dr. Asia Lyon: Google it?

Kevin Adams: Google, Google it. Is

Dr. Asia Lyon: he from, is he from Detroit or No, he's from

Kevin Adams: Denver,

Dr. Asia Lyon: bro. Listen,

Kevin Adams: okay. Never at first when he started, well, hold on Asia, because you know when a white boy says Detroit's known as midnight. I'm like, what do you mean? What you, what you saying? What you saying

Dr. Asia Lyon: sir? Sir. Sir, sir? No. Yes. Uh, tell your friend ne nevermind.

Kevin Adams: We, we, we gonna get into it. We gonna find out. We will. We let, let the people know. I'm sure the exit interview audience will let us know.

Dr. Asia Lyon: They will. [00:04:00] But in the meantime, let's go ahead and get this interview started.

Kevin Adams: Let's get to it. How is everybody doing? We are back with our guest Dr. Desmond Williams. Is it doctor?

Desmond Williams: Just Desmond Williams.

Kevin Adams: Just Desmond Williams. I, I always give, I what I always say, it's like a hood doctorate, you know, like anybody who's dropping knowledge as a doctor in my mind, like you don't need the degrees. But, uh, we are here with, uh, Desmond Williams, and he is, is going to go through his story of his exit interview, um, in Asia.

You want to kick us off?

Dr. Asia Lyon: Sure. Hi everyone. Welcome to season two of the exit interview. So, um, you know, as always we invite dope folks onto our podcast, um, to share their story. And so this today is no different. Um, Desmond Williams has been on to dope teachers in the past and he's come back and graced us with his presence [00:05:00] for the exit interview.

So, as always, we just want to, um, ask like, what's your story? And the same questions we always ask everyone and just share with us. So starting off, tell us about your educational journey. Where did you teach? Who, what grades, which courses, whatever. Go ahead and get started.

Desmond Williams: Well, um, Asia and Kevin, thank you for having me.

Um, I think this conversation is, is so important just given, um, I was doing some reading and 4.8% of all teacher jobs or teaching vacancies. Teacher jobs are open right now.

Kevin Adams: Yep.

Desmond Williams: Which is the highest it's, it's ever been since the Bureau of Labor and Statistics has kept such data. So I think this is such an important, uh, conversation.

And I, I remember being a principal and when teachers leave who are not being promoted. Right. My whole thing [00:06:00] was, um, you're not gonna leave here unless you're getting a promotion. You can't leave my building and take a lateral move somewhere. So when you, when you conduct exit interviews, you want people to, to be honest and, and kind of square dealing and, and why they're deciding to, you know, take, um, other steps.

But to, to answer your question directly, um, this would be year 20 for me. I started teaching in Washington dc I was, um, fortunate enough to get accepted into a. Um, a alternative teaching certification program, um, called the DC Teaching Fellows, which was under the New Teacher Project. And that year there were cohorts in, um, here in dc uh, Houston, Philadelphia, and I think, um, I think, uh, Atlanta, if I'm not mistaken.

But, [00:07:00] um, I was a special education teacher. I taught, uh, third, fourth, and fifth grade special education students at that time. You know, you taught full-time and I was at a full-time master's program at George Washington University, and I just remember being at like an amazing school with amazing teachers, amazing community.

Our school was, um, this was a DC public school and we were about 45%. Um. Latinx and maybe like half of a quarter of a percent white and the other 54% African Americans, but just a thriving community. Lots of great teachers, um, young teachers, veteran teachers, um, people of different, um, racial and ethnic backgrounds.

And it was a great opportunity for me to learn and cut my teeth and [00:08:00] become a good teacher. So,

Dr. Asia Lyon: yeah. And you were there for how long? And before you be, you said you, you were, were an administrator, so like, love to hear about that too.

Desmond Williams: Well, so that Raymond is the beginning of my career. Um, my principal at the time was a, um, black male by the name of Timothy Williams who was, um, old enough to be my father.

But there was all, there were rumors that he was going to retire. After my second year, um, I mean, I, I don't know how much time we have, but there, there's always that, um, I think for a lot of men in education. I remember the middle of my second year, um, going to catch up with some of my fraternity brothers, and we hadn't gotten together in a long time and, um, I hadn't seen some people in a long time.

So we're, [00:09:00] you know, getting together at a friend's house. And one of my line brothers pulls up in A BMW. Um, another bro that I really respect, um, pulls up in a, in a Range Rover. Um, another one of my alarm brothers pulls up in a brand new Pathfinder, and I'm like, these are, you know, my friends, we went to school together, but mm-hmm.

My grades were just as high as any. I've seen their GPAs. That's right. I've seen your transcripts. Like I know how we got down to get through this process. Like, well, what, what decisions did I make wrong? Because I was catching a bus and walking. Right. And I actually purposefully chose to teach at Raymond because it was only like a nine block walk from my house.

So the itch, um, to make more money was a thing. So to answer your question, Asia, I left Raymond after two years and went to, um, a [00:10:00] private school for children with special needs. 'cause it was a, um, not a big jump, but it was a bigger jump in pay. Um, and the school was looser, which gave me a, it was disorganized, which gave me the opportunity to kind of think about, um, cutting my teeth, doing something very different.

So, um, I was there for two years. I taught for that two year period. But I was also a special education, um, coordinator. That fourth year after that, I went to work downtown for DC Public Schools, um, in the Office of Special Education. And then I took a job at another private, um, school for children with special needs.

And that was my first foray into, um, into administration. Um, and then I kind of toggle back and forth. I had an experience where, um, well, let me say this. I, I enjoyed my time in administration, but [00:11:00] um, I made moves for the money. You know, like it was very tough. Um, making $42,000 a year and driving a fire engine red.

Um, Volkswagen Jetta, when, when people who you feel that you're equally yoked with intellectually and talent wise are driving range Rovers, like, it's really tough. Um, particularly in a place like Washington, DC where you're judged by, um, such outward appearances. And I think that's the most diplomatic way that I can, I can say that.

So I don't think I was, in retrospect, particularly ready for administration, but financially it was a right move and it was something that, um, my family, specifically my parents, 'cause I was single, it was something that they needed from me. Um, [00:12:00] even though at the time they didn't know it, it was like, oh, you can send us money.

Mm-hmm. Well that's a big, that's kind of a big deal. Keep it, keep it coming. Right? Or they wouldn't have asked for it if I didn't have it.

Dr. Asia Lyon: I, that's so interesting. I think that, and Kevin, correct me if I'm wrong, I think you're the first person we've had on the show that actually talked about like the financial making these moves for the financial reasons. Right? Not to say that you're the first person to think about the financial piece, right.

noise: But

Dr. Asia Lyon: just to admit that out loud, and I appreciate that honesty and to say like, you don't, you don't believe that you were prepared or ready for an administrative role. Right. But like, financially, in a place like dc, which sounds a lot like Detroit to be honest with you, when it talks about outward appearance, especially cars that you had to make these moves for, for all those reasons and that pressure from your parents.

So that's really interesting.

Desmond Williams: Yeah. And it, and [00:13:00] it wasn't, um, it, it wasn't pressure from my parents, but it was one of those things where, um, there's no such thing as extra money. So when you're able to send money home, like my father borrowed from his 401k to pay for my undergrad. So if you're able, you know, and that was like 40 grand.

Um, but if you're able to send home, you know, 600 and $700 a month, that's a, that's a game changer. Yeah. Um, and the, the, the finances of it, you know, I was a teacher who was very serious about my craft. I was one of the, um, first people in the building, one of the last people out of the building. I spent all of my planning periods and other teacher's classrooms.

I asked questions like, why is this like this? Why is this like this? I, [00:14:00] um, and when you are serious about your craft

as a.

Mail and when to get

Desmond Williams: your honey, when you get your money. Mm-hmm. It's very easy to get pushed towards administration because people see you as being a, just a leader. Right. Um, so, you know, I didn't just say, man, let get this money. People were pushing me in that direction as, as well, particularly, um, when I went to the private school, like there was just a lot of opportunities of, it was just all of these gaps that we had because we were under sourced, underfunded, undermanned, under professionalized, and there were just a lot of opportunities for me to, um, fill in gaps in certain places in terms of what we needed as a, as a staff [00:15:00] and that kind of.

Shape the way I thought about organizational behavior and shape the way I thought about, um, training teachers and shape the way I thought about budgets. Um, because that's one of the hardest things when you move into administration. It's like, okay, you're gonna take money from some place to, to do something else.

So, um, I thought I was ready. Um, but no one tells you that just because you're like a really dope teacher that, um, it has absolutely nothing to do with being even okay. Administrator. Those are two, those are two separate things. No one tells you that. Um, it's like, oh, he's a great offensive coordinator.

That doesn't mean he can be a head coach. Right? This is, he's a great salesman. Doesn't mean he can be a vice president of [00:16:00] supply chain. Those are. Right. Like the things that got you to where you are at this level, um, require a different skillset when you're managing, um, and responsible for other people and evaluating other people.

Completely different ballgame.

Dr. Asia Lyon: Yeah. It's interesting that you, I'm glad you talked about like, um, men being in administrative roles because just reflecting back on my own career in teaching, I had four male principals and one female principal, and, and there were so many men in like the, um, like, I don't wanna say main office, but like in the, whatever they call it, downtown, some people call it, or like the central

Desmond Williams: office

Dr. Asia Lyon: Central.

Thank you so much. Central office and so many women in classrooms. Right. And that was always this conversation that men just seemed to move up so much more quickly than women [00:17:00] in the district where I worked. Mm-hmm. So that, that's, I'm glad we we're talking about that.

Desmond Williams: Well, America is a sexist country and even though, um, and Kevin, you made a, you, I should know the numbers 'cause I've researched them, but like 80% of the people in K 12 are women.

noise: Mm-hmm.

Desmond Williams: I believe 53 or 54% of administrators are men.

Kevin Adams: Yep. Yep.

Desmond Williams: Those numbers might be off, but, um, I'm, I'm doing some, well, I had been conducting research for the second edition at a Burning house, but those numbers are probably off, but that's national. That's the National Center for Educational Statistics.

So we still have, um. An imbalance or a glass ceiling of women not being able to move into, um, administrative roles despite, [00:18:00] um, the sheer numbers that they represent in classroom positions.

Kevin Adams: Yep. Right. Right now what I see is, uh, 76% of public school teachers are female or female, 24% male, and this 2017, 2018 school year.

Mm-hmm.

Kevin Adams: Mm-hmm. And then, uh, with the lower percentage of male teachers at the elementary school level, 11% versus at the secondary school level is 36%, which is what you see Right, right. Middle and high. The more prestigious education gets, the more male it gets. Mm-hmm.

Desmond Williams: Mm-hmm. Or the, the less opportunities to Yep.

Change, change diapers and Yep,

Kevin Adams: yep. And work with young

Desmond Williams: children.

Kevin Adams: That's right. That's right. Yeah. That's right. So when, when, when, when I hear your story, Desmond, I, I always think about like, um, you know, and I think the, the, [00:19:00] the money aspect is always, you know, I think it matters. I think it matters to us as black professionals, you know, and I love when we think about like, who we go to school with and the work that we did, because we're taught, you know, I think in our community that this work is going to equate to, uh, a better a betterment for our families.

You know, that, that's like the real reason why we do it, let's be honest, right? Mm-hmm. But like, when, when did you have any kind of, uh, you know, this, this thing that we hear about on the, um, the exit interview is, I'm leaving my kids, right? I'm leaving these kids behind who need me. And as a special educator, as a black special educator, a black male, you know.

Uh, we know what the situation is. How did, how did you deal with those types of, that, those types of feelings and that process, you know what I mean? And, and what do you think about that, those types of thoughts and attitudes when it comes to making these [00:20:00] transitions?

Desmond Williams: Man, that's a good question. My, my first year teaching, um, I had a student by the name of Antonio Wynn, and I can say his name 'cause he's like 30 now.

Yes. But, um, blessings. Blessings. I remember we, uh, came back after spring break and, um, like I was a resource teacher, so I had to go to regular ed classrooms to pick up my students. Yep. And, uh, he was in third grade, he was in Miss L Brown's class. I'll never forget Laverne Brown, um, because she was my mentor teacher.

But I went to pick up, um, Antoine Jowan and this other kid named Joseph Anderson and, uh, Joseph. And, um. Jwan came to the door and I was like, where's uh, where's, where's Antonio? And Joseph was like, Ms. Brown said he don't go here anymore. And I was like, Ms. Brown, what's, what's up? She was like, baby, he [00:21:00] gone Ms.

Uh, she was like, yeah, Ms. Eson told me this morning, they moved over over spring break. And I was like, the dog that's like DMX said that's my man. Like

noise: mm-hmm. She was

Desmond Williams: like, baby, he gone. And Ms. L. Brown was, I was 25. Ms. L. Brown was probably 60, right? Just like hardcore, like finished undergrad, went into teaching.

Right. Um, like 30. She was like, if you stay in the game long enough, you gonna lose kids. Right. And uh, she was like, if you stay in the game long enough, you gonna teach your kids kids. Like, that's just part of the game. And I was like, well, what's gonna happen to him? She was like, baby. And she said this in front of all her third grade class.

Yeah. She was like, baby, he gonna get another teacher. And I never, they did that, didn't mean anything at the time, but her words [00:22:00] stuck with me because she was teaching me how to be a professional.

noise: Mm-hmm.

Desmond Williams: Um, so to, to answer your question directly, Kevin, I have never, um, not considered my students and their families in the moves that I've made professionally.

noise: Yep.

Desmond Williams: But I also, what I also remember what Ms. L Brown taught me in terms of if you make decisions like that, you won't make the de the decision that's best for you. And ultimately, um, you have to remain responsible. For yourself. And I, I think of that as a, a single male who didn't have any family in Washington DC

noise: mm-hmm.

Desmond Williams: Versus really embracing that once you become a married man and have children on children of your own. Yep. Yep. Right. Um, your family becomes the, [00:23:00] the, the priority because, um, you know, that's just the way things are. But, you know, I, I had some amazing relationships with, with students. I think kind of as we Right.

Kind of moved towards the early 2000 and tens and things like that, social media makes, um, the opportunity to maintain those relationships, um, even easier. Mm-hmm. Particularly with younger students, you can connect with families and, and things like that. If you're someone who works with high school, you know, it's, it's just kind of easy, like, yep, here's my phone number.

Call me, I'll email your mom and. We can go to a Georgetown gamer or something like that on a weekend. But with, with younger children, you know, connecting with families through social media, those things are, are important. But ultimately, um, not to beat a dead horse, it's something that I considered, but it wasn't a major factor, um, to the degree that I, I have [00:24:00] seen, um, like I've had to force people as an administrator to take the next step because they were worried about their relay for the, and let me tell a quick story.

Um, one of my teachers got an opportunity to work at a prestigious, um, private independent school in Miami. And she was thinking about staying because. Her what her rationale was. Well, but we're really starting to get somewhere and their progress in math. And I just looked at her, I said, girl, I'm gonna find somebody to replace you.

Like we gonna find a math teacher, like move to Miami, right? You'll be closer to your family. They're gonna pay you $20,000 that I cannot match. Go ahead and make that move. [00:25:00] So I have, um, seen people stay in places too long for reasons that, um, that I think, you know, could be justified, but at the same time, they could be easily as justified in, in making those moves.

And that, that's kind of how I approach this. Going back to what Ms. L Brown said,

Kevin Adams: I feel like you're singing Asia's, uh, pim.

Dr. Asia Lyon: Yeah, yeah, for sure. Like, I don't know. And, and this is, so I don't know how much you have a chance to listen to the interview, but we talk a lot about racial battle fatigue

noise: mm-hmm.

Dr. Asia Lyon: And how educators experience racial battle fatigue.

Um, typically it's been around like white administrators, the system itself, um, white parents, um, colleagues and things like that. But in a place like DC where the demographic is, uh, much more diverse, did you experience any racial battle fatigue as you were going through the [00:26:00] systems or not going through the system, but like teaching and the administration being, um, in those different offices and spaces?

Desmond Williams: So, um, that's a tough question because.

So let me go, take us a little bit outside of the box here. Um, like, would we think a Marcus Garvey or a Harriet Tubman suffered racial battle fatigue?

noise: Hmm.

Desmond Williams: Like, I don't, um, I don't, I've always worked in the hood and there have been white teachers in the hood, but I've never worked with a white administrator, so let me say that off the top.

noise: Mm-hmm. [00:27:00]

Desmond Williams: Um, in some ways I would argue, um, you don't need to because, um. Part of the system or part of the genius of white supremacy as a system is that it doesn't need white people in place in order for, for the system to run efficiently.

That's right. In, in fact, um, I was listening to staff members at a school have an argument over this notion of exposure and their ELA curriculum is at a middle school. And the only white person on the call was saying that the kid kids definitely should, um, read Tennessee Williams, um, so that they can be exposed.

And I hate that e word because ultimately what that conversation, what that phrase is saying is that, um, black people have to be exposed to what white people [00:28:00] know in order to be validated by a system of white supremacy. And when you look at the inverse, um. A middle class white school, um, in the suburbs, you don't have white teachers saying, you know what, I think our kids have to read some Christopher Paul Curtis.

Mm-hmm. So they could be exposed to the African American experience. It's, it's not a, they don't talk like that. Yep. So, um, I say all of that to say if there was any fatigue from racism, it was because of how the system operates and how it grinds against, um, African Americans seeking a freedom that solves white supremacy.

Right. I talk a lot about, in the book this notion of what do [00:29:00] black people want from education? Do they want access to a middle? To a middle class lifestyle, or do they wanna end white supremacy? Because you're gonna have two different educational paths. You're gonna have very different curriculums based on what you want your outcomes to be.

So I would never say that I left a school or left teaching because of racism, because, um, as the honorable Elijah Muhammad said about this notion of black people separating, it was like, where are you gonna go where white people are not in control?

noise: Mm-hmm.

Desmond Williams: So like, I would, I would ask your folk who've, who've been on the show, if they left, um, like where did they go and not experience racism?

Like, one of my heroes, um, who I think everybody should read is Gentleman is, uh, his name is Neely Fuller. And, um, not to go too deep, but he was a, [00:30:00] um. He was a colleague of Dr. Francis Kre Welling. Um, and he was the first person who she heard say that racism is a system. And he said it operates in economics, education, entertainment, labor, law, politics, religion, sex and war, all areas of human activity.

So like, is the racism more palatable at this school? Mm-hmm. Like, like, like, I don't know. Um, so that's, that's not why I got out the game. And I, I, I can't be who my heroes are, but like, like what stopped Harriet Tubman from making a quote unquote 20th trip? They say she didn't make 19 trips, but let's just say for the sake of this conversation, she did, did she say what the fuck with this racial battle fatigue?

I'm not making this trip. I don't, I don't buy it. I don't, I don't, [00:31:00] I don't buy that. Um, may, I could be wrong.

noise: Mm-hmm.

Desmond Williams: But that's not, that's not my narrative. It's not my narrative.

Dr. Asia Lyon: If we had time, I would love to talk about that point, because you asked a great question, like, where did they go? Right. And we can talk on and on about like, the folks in season one and even my own story about where did I go mm-hmm.

When I left the classroom, the traditional classroom. Mm-hmm. Um, and to just make it really short, super, super short. I don't think there's any, like, running away from racism is foolish to believe that in my mind it's the turning it down, the volume down from a hundred to 99. Mm-hmm. And if I can just, if I can just function at 99 on the volume of white supremacy by whatever that looks like, um.

Then I'll take that, that notch down one. [00:32:00] But there's never ever going to be, I don't feel like people believe this, and we should ask that question, Kevin, but I don't think that folks in our, that have come to our podcast and talked about where they are now have ever said, and now I never experienced race, racism related stress or racial, because like you said, that's, that's like foolish to believe.

noise: Mm-hmm.

Dr. Asia Lyon: Right. Absolutely. Um, um, so yeah. Um, but you did leave education or traditional classroom and administration and we are gonna talk about that after our break. So we'll stop here and then we'll come back in a few minutes.

Okay.

Gerardo: Hello listener. If you've made it this far into the episode, perhaps you are enjoying this remix conversation about power, culture, and education. And if that's the case, please consider joining others like you, educators, community leaders, activists, scholars, artists and youth by supporting the AU Peaches and a MIC [00:33:00] podcast and productions on Patreon.

For as little as $5 a month, you can get on air shoutouts, sneak previews, and early released episodes. Insider information on the happenings in two Dope Nations and many. Other small benefits. The greatest benefit though, is you enable us to keep bringing the fire because of people like you. We have expanded to two podcasts with the exit interview, taking flight and forcing hard conversations about attacks on black educators.

And we've added new features including episode transcripts and a revamped website, all because of listeners like you. But that's just the beginning. Your support will open up new possibilities for us and for the communities we represent and advocate for. And at the $15 per month level, you receive a sticker.

Yes, folks, a sticker. To support the podcast, head over to patreon.com/two Dope teachers. That's patreon.com/two [00:34:00] Dope Teachers.

Kevin Adams: We are back here with. The amazing Desmond Williams. Um, and so we are gonna continue on with his exit interview, um, Desmond. So, so you've told us so far about how you got into education, that kind of movement, um, your, some of your experiences and then, you know, that movement from out of the classroom into administration.

So, so tell us about like where you're at right now and what you're doing and, and, and, and how you're approaching being an a black educator.

Desmond Williams: Yeah. So, um, I literally, um, in 2000, uh, 16, I left the classroom to become an administrator, um, at a school that I was teaching at. I was, um, at an all boys school in a district.

I had taught there for four [00:35:00] years and I moved into administration and I really wasn't, um. Very interested in going back into administration. I was, um, in 2011, I was, uh, working as a, an administrator at a charter school and I was fired after working. I was, I started, um, July 5th, right? Um, at the turn of the new fiscal year.

And I was working as an assistant principal, and myself and my principal were terminated together, um, right before Christmas break. So I went back into, um, which is a entirely different story, but I went back into the classroom, um, fell in love with, um, teaching quote unquote regular ed students. Um, and then was asked to move back into administration, um, at that [00:36:00] same school and.

Administration was not something I really wanted. Um, but I think for me, the, the leaving, um, traditional K 12 was about betting on myself. Um, and we, we talked about this, Kevin on the, on the podcast, I told the board, I told my boss that if you pull me out of a classroom, like I had made my classroom a demonstration space for educating black boys, and I was gonna, um, replicate that throughout the entire building.

Mm-hmm. I was gonna turn it into a demonstration school for black boys. And for the most part I did that. I turned it into a school with boys, um, to a school for boys. And then more specifically, turned it into a school for black boys. Mm-hmm. Um. And I had [00:37:00] pretty much reached my ceiling in terms of what I can do there.

And I, you know, we talk about racial battle fatigue. Like we could have an extended conversation about what it's like to run a school with all black boys to have a staff of 23 and have 17 of those, uh, staff members be black males. Yes. Like there's a, I mean, you talk about, um, because I was hell bent on doing that because I thought about, um, what they might not get in other places.

Mm-hmm. And how, um, we don't think of black men as being diverse and giving our boys the opportunity to figure out something that I didn't figure out until undergrad.

noise: Mm-hmm.

Desmond Williams: And that was that black men are very diverse and you can take any, um. Homogeneous group and they're very [00:38:00] diverse. That's right. We really look.

So, um, that was, um, a labor of love, um, because we got some stuff with us as black men when we come into, when we come into educational space. That's right. Um, that's right. And I mean, and I mean that in a good way. Yep. But for me, um, it was about, I have reached my ceiling here and I think I can, I think I can bet on myself in terms of moving into, um, in terms of moving into consulting and bottling all of my experiences and using those experiences and leveraging those experiences to help, um, other schools.

So for me it was about, um, it was about impact. It was about family. Um, when I left, um, K 12, at [00:39:00] the time we had, my wife and I, we had just had our, um, second child. She was born in May, and I walked out the door. Well, I kind of had walked out the door in February, um, but I officially walked out the door. Um, like I had made the decision in like March.

Mm-hmm. Um, but I walked out the door July, June 30th, if you will. Um, but for me it was, um, I think I can, I think I can bet on myself and I didn't know if I would have a better experience professionally than I had there.

Mm-hmm.

Desmond Williams: Um, maybe I could, I don't know. But the impact, the leverage, the work life balance was a real, were were things that we just had to have.

Um. Because you're talking about a young couple with a 4-year-old, I'm sorry, a two, a [00:40:00] 3-year-old and a two month old. Like, how do you balance those things out? Very real, very real.

Dr. Asia Lyon: Yeah. I have a question about that. So, um, one of the questions we like to ask folks is like, how did family respond, cope, support you in that decision?

And so you mentioned being married, having two small children. What was that conversation like with your wife when you said February or probably way before, like, I think the next move is this, like, what was that? I see you shaking your head. What was that like?

Desmond Williams: So describe

Dr. Asia Lyon: that to us.

Desmond Williams: Um, there's some pain points there that I don't know if I, I really wanna go into, but I will say this.

That's fair. Um,

I think I'm pretty good at being married. But don't do what I did because I told my wife weeks leading up to [00:41:00] my leaving, like I was getting contracts behind the scenes. And um, like she, there was some dysfunction between myself and my assistant principal and, and she thought it was that. Um, but it, but it really wasn't.

It's, it's, it's literally, um, and I think we said this on the initial podcast, Kevin, like, uh, you kind of have to get out of the boat if you're gonna walk on water. That's right. That's right. And, you know, I thought it was something I can do and it's, it's been some really rough, rough waters. Let me, let me say that.

And, uh, St. Peter has drowned a few times, right? There's, there's that. But, um, you know, ultimately my wife has been.

Very supportive[00:42:00]

of

Desmond Williams: not having autonomy. And I think that's a great thing about being a teacher. You get that autonomy. But, um, yeah, I, I, I would say don't tell your listeners don't do what I did. 'cause I had made the decision and I tell a story that falls in with racial battle fatigue. Can I tell a story? Of

Dr. Asia Lyon: course. Yeah.

We love stories on this, on this podcast, right Kevin? So

Desmond Williams: I was in, um, my leadership team meeting and I used the, um, the word my purposefully, because these are my department heads and, um, our outplacement specialist slash music teacher. Slash um, he wore a lot of hats 'cause he just made up stuff for him to do, which was pretty positive for the most part.

[00:43:00] Right. But, um, he came up with this great idea. He said, you know, we need a, um, we need a logo for the school. So in this meeting we decided that the kids would have a art contest and they would vote on the best piece of artwork to be the logo School's nickname was the Kings. Mind you, I had taught, um, the sixth graders at the school, the fifth graders at the school, the fourth graders at the school.

Um, I had thought taught those three cohorts. That's almost half of the school. And, you know, I keeps it ligety, ity, blinkity, ity, black, like all black, everything. Like

Kevin Adams: blacker than black. 'cause

Desmond Williams: I'm black. Y'all black. 'cause I'm black. Y'all like, even the tips on the, the tips of the shoestrings was black.

That's right. That's right. That's right. So one of our [00:44:00] kids, I'm sorry, two of our kids came together and they created a, um, a pharaoh on a chariot pulling a horse. I love

Kevin Adams: that.

Desmond Williams: So a few weeks later we're back in my meeting and my music teacher is in the meeting and she was like, and she's proud. She's like, um, Mr.

Scott, this is the, this is the logo they created. And Mr. Scott is a music teacher slash outplacement specialist. My director of development, who doesn't report to me, he reports to the head of school. Um, so in that sense, we're equal. Like he keeps the lights on. He said, um, what is that like white guy like wolf on Wolf of Wall Street, like just go, gets money.

Like that kind of a guy, right? [00:45:00] And um, she said, yeah, this is a logo that the kids created. So I looked at it and I said, oh, that's dope. And Mr. Scott says, um, and Mr. Scott, a few years older than me, Morehouse grad, and I'm purposely saying his name, because you have to own the things you do, whether they're good or bad.

That's for Scott. He said, I can't do anything with that. And I was like, what's wrong with it? He said, I mean, that's Egyptian. He was like, it's too ethnic. And I said, well. I don't know about ethnic, but that is what our kids think of when they think of a king. And that is what they think of when they think of themselves because their parents gave that to them.

And I reinforced it through the ELA and social studies curriculum that took me two summers to write. Yeah. He was like, I'm, he was like, we [00:46:00] can't do anything with that. And then the director of development, his name is David Shepherd, he's gonna own it too because he is racist, says, um, I don't know if I can get donors to give to the school if they see that we can't put that on letterhead.

And I said, your job is to raise the money. It's my job to deal with the programming that happens in the school. If you can't do that, you need to get new donors or you get the, you get the go job hunting and freshen up your resume. So my boss, who is. The head of school, um, was not in that meeting. The head of, um, the direct director of development and, um, music teacher slash outplacement people say, Mr.

Williams is not really thinking about the best interest of the school. Um,

Dr. Asia Lyon: oh, wow.

Desmond Williams: He's not being [00:47:00] political, da da da da da. Like political as a, as a loaded term. Yep. Mm-hmm. And, um, I said to, so this comes to me from my boss. Like the four of us didn't sit down and have this conversation. And I said to my boss, I was

like.

Three years, right? That's right. He was gonna

Desmond Williams: do three years and he was gonna retire. So the plan was for us to walk out the door together. Yeah. But what I, what I said to him was like, how, how can you feel comfortable with a, um, director of development who doesn't believe in a [00:48:00] racial pride of our people?

Like how does he get to have a job here if he doesn't believe in what we're doing? Like by definition, he's using this place as a stepping stone. Yeah. Like the things I was like teaching our kids to love themselves is no different than teaching them four plus four equals eight. He doesn't believe it's necessary for us to teach our kids four plus four equals eight.

And I could just see my boss, um, who is a black man who I love and respect and adore to this day. I could see the discomfort in his face, like the, a decision was gonna have to be made. And I, I just said to myself, you know what? I, I can bet on myself. So William Smith might call that racial battle fatigue, but I just call that, um, knowing that we had some [00:49:00] amazing relationships over that time and we did some amazing things in the six years I was there.

Um, we were able to touch and help a lot of families. Um, I have three teachers on that staff who are assistant principals now. Mm-hmm. Um. All of which you left after I left, which kind of sucked. But, um, just knowing when your time is done someplace, um, and, and thinking that I would not be able to match that experience someplace else.

So, you know, ultimately that was my foray to, to go and, and, and, and bet on myself and, and get out the boat, um, if, if you will. But there were a lot of other things that were happening. Like when you talk about a straw may, maybe that was a straw, but at other points I was just like, man, it would be dope if we could just get [00:50:00] money to go on like a civil rights tour.

Yeah. It would be dope if we could. And, um, you know, I, I just thought that, um. There was more that there was some more that could have been done, but, um, I didn't know if I was the person to lead us there. And, and, and that's why I decided to, to walk away.

Dr. Asia Lyon: Yeah. That's so good. That's so good. And I guess, you know, and you, you said, I don't know if Dr.

Smith would say it is, but really we get to say what it is and what it isn't. Right? What racial battle fatigue is or isn't. Yeah, I say that tongue

Desmond Williams: in cheek. It, it's not racial battle fatigue. That's just like, how would you, like if I had wanted to stay, like how would I confront that?

Dr. Asia Lyon: Yeah, for sure. You

Desmond Williams: know, because [00:51:00] I pushed that logo,

I pushed that logo. I don't know what they did. It's been almost four years.

Kevin Adams: Yeah,

Desmond Williams: but I was like, oh no, that's the logo. That's it. I'm saying, and if it is not gonna be, I'm gonna terminate you, but before I do, you are gonna go in front of the student body and say, why, what the kids had already voted on doesn't get to be what students voted on.

You go tell 'em. And then do

Dr. Asia Lyon: you think that, I'm sorry, I I'm sorry to cut. No, go ahead.

Desmond Williams: Do you I was gonna curse, so yeah, cut me off.

Dr. Asia Lyon: So that, I think this is an interesting piece is like that around power, right? And like you, like you just said, and I'm gonna terminate you and I'm going to do, you're gonna do X, Y, and Z before that happens.

And so just thinking about some folks that have [00:52:00] come on here who just, and their belief, they may have but just didn't realize it, didn't utilize it, and their belief didn't have the power. To do anything more than just, except for the time being, strategize to leave and then to leave. Right. And so I think, and I'm not, I can't, I'm not jumping into anybody's head or anybody else's story.

Mm-hmm. But I think it's important to recognize that that being able to be an administrator role for some folks could have been, could have changed the path in which they went. Right? Mm-hmm. Um, for you, you said, I bet on myself, you had done all these great things in the school and for years before that, I just think about like how many of our black educators across the United States and, uh, beyond, if they had had an administrative roles, would that have made a difference?

In some cases, I'm thinking not, and in some piece, in [00:53:00] some cases I'm thinking so, but it's just hard to know, I guess.

Desmond Williams: Yeah. I think it's, I think it's hard to know that So can I, I tell you. A realization that I had when I first became a principal. I took over as a principal of a school in April of 2008.

That was like probably in the history of mankind,

one of the most GL

glorious,

Desmond Williams: and I don't know if there was ever a time, easier time to be a black man in America. What I figured out that first full year being an administrator is, yo, you work for everyone in the building. You work for the custodians, you work for the landscapers, you work for your teacher's aides, your teachers, your students, the cafeteria workers, both [00:54:00] nurses, right?

You work for everyone. The. It, it, it may have seemed like a power trip to say I was gonna terminate him, but hey, that's not true. I'm saying that tongue in cheek, I was taken aback at the amount of power I didn't have to the degree that I was, um, a buffer between the staff that I had to protect and the minutiae from the people who work on top of me.

And it was like, you gotta protect these people, quote unquote, underneath you because the winds and the whimsical of what comes from up here will drive your teachers and the people in the classrooms and in your building crazy.

noise: Sure.

Desmond Williams: So that was very fatiguing [00:55:00] and learning how to do that. And build a culture because the culture of this particular school was broken.

This, the morale was very low. I took over in April and we had a student who, um, who passed away, um, right before the holiday season. So it was just a very, um, somber and solid based, like trying to juggle, building people up, you know, starting afresh, um, creating a culture, starting afresh, but still maintaining a level of accountability and then the protection.

Um, but it, it's really been like that. Um, at the other two schools I was an administrator at as well. Not necessarily the cultural aspects, but that buffer ness. Um, so I don't, I don't know, I think [00:56:00] individually your, your guests will have to answer that. Um, but the families of your staff become, they become your children because if a staff member can't come to work, um, you know, you're paying for a substitute.

Um, you hear the stories of, you know, my grandmother, um, has cancer and we think she has a week to live. And you, you know, you don't think of that transactionally as, I have to find a sub you, you feel for those people. So, um, the, the wear and tear emotionally, um, is, is a real thing. And I think you find yourself, um, being more in service, at least I found myself being more in service and being more emotionally attached to people once I moved into administration to the degree that, um, I don't [00:57:00] necessarily think I had more power.

Um, there was just certain things I could do, um, like change curriculums, right? Or call this person in to do a pd. Um, there obviously there's some things you can do, but other things, um, got in the way of, oh, I can have this person come in and do a PE pd or I can do this curriculum. There there's, there's some give and take there.

Yeah.

Dr. Asia Lyon: Thanks for that. So I guess we're at our last question, which, um, is, what are you doing now? You talked about leaving, talked about telling your wife, but Not really, but kind of Right. Telling my wife. Not

Desmond Williams: really, but kinder. That's, that was it.

Dr. Asia Lyon: Yeah. So like four years out of the traditional classroom space.

Mm-hmm. Tell us what you're up to. You mentioned kind of in the beginning, [00:58:00] you hinted around at a book. You've talked about consulting, so we'd love to hear about all of that. Please.

Desmond Williams: Yeah. So I am, uh, the, the founder of Lanka School Solutions. Before I got on the phone with phone with you all, I was, uh, on the phone with my web developer.

We're launching a new website, hopefully like at midnight tonight.

noise: There we go.

Desmond Williams: Um, my Linka is dedicated to helping our most marginalized students have the school experiences that they deserve. Yes. Um, our focus is on, um, strategic planning. Um, but more so than that, the execution of our plans to help schools be the schools they need to be, to help districts be what they need to be in order to support, um, said marginalized groups.

Um, so, you know, [00:59:00] professional development, um, focusing on differentiation, reading instruction, restorative practices, um, are kind of some of the main components. Um, and with that, um, we get to lift up the hood and, and talk about what's happening with black and brown boys, um, and what's happening with our sped populations because those are the groups that tend to not, let me restate that Statistically, those are the groups that, um, perform the worse academically and socially.

So, um, how do we help and support those groups? Um, I'm in the process of publishing a second edition of the Burning House, educating Black Boys in Modern America. Um, if you go to the website, you could purchase the book, well, depending, um. You can pre-order it now. The book, um, will be available on February 28th, but you can [01:00:00] pre-order the second edition.

The first edition is available now. Um, and you can purchase that on a website or on Amazon. So we're just, um, trying to make school spaces, um, better for all children. Um, so this, I, again, this idea of working in a system to, um, break it ultimately Yes. Yes. Ultimately to, to break it. I, I think we're, um, one of the things that I really wanna do, we were talking about this notion of black male educators.

I think we have to create, um, 'cause I don't know what public school is gonna look like with COVID in four years versus 10 years. And I, I sincerely believe that we need a national union for black male educator. So that we can leverage our collective power, [01:01:00] um, to get more money to be in these schools.

Meaning if you're part of a union and you work here for 85 grand,

Kevin Adams: yes,

Desmond Williams: wouldn't you go and work here as part of this union because we know where the openings and, and the vacancies are, and we're gonna negotiate on your behalf and we can get you 102 K to work here. Um, I think that's kind of where my mind is around how do we keep people in spaces?

Because in schools, because again, in white women, Asian women, uh, Latinx women, everyone's, everyone's leaving the profession. Um, and, and record numbers. Um, and, and people in record numbers are just leaving. Um, all kinds of occupations in general. So like, how do we keep the people who wanna be there? And I, you know, I think there's [01:02:00] some things that can be done, but, um, COVID is a monster.

So you have, we have to be out thinking outside of the box in order to make it happen. So that's a, a pet project that I would like to be a part of. I just can't spearhead it myself. Right. I don't know. The first thing about unions, um,

Kevin Adams: oh yeah. Oh yeah. It's hard. And I, I will say as a person who's a part of my union and on our bargaining team right now, somehow ended up there.

Mm-hmm. Uh, you know, I think it, we need more black faces in these white spaces, you know what I'm saying? Because these, these are, these are places that historically have denied us. Access. Right? We, we, we were not allowed into unions and uh, I think we need our voice to be heard. So, uh, yes. I, I, as much as I find out I will, I will pass it all down The, down the, yeah.

Let's down the line.

Desmond Williams: Let's, let's talk. It's not something that I can do, but [01:03:00] I,

Kevin Adams: it's an important part of it all. Yeah. It's an important part of it all.

Desmond Williams: Like, I, I just think we have to,

Kevin Adams: um,

Desmond Williams: think differently. Like, there's so much opportunity because of COVID and, you know, power hates a vacuum, right? Um, someone is going to fill those vacancies

Yeah.

As we

Desmond Williams: leave. And if they're not qualified, if they're not caring, then what, what would that mean for our children and children who look like us? Because ultimately this is about the service of our, of our children. And, um. Again, educating our children and our people enough where we can create a world without white supremacy.

Dr. Asia Lyon: Mm. Yeah. I would, I wanna say, shout out to Dr. Antoine Jefferson, who, um, I've been in his classes several times over [01:04:00] the last couple semesters, and he always asked the question of like, what does liberation look like? Mm-hmm. Right? What does a liberatory education look like? What does liberatory schooling look like?

And like every semester, we never have an answer. Mm-hmm. I don't think, I don't know. And I don't know why, maybe 'cause I've never seen it. Right. Maybe because it, I don't know. But we don't know what it

Kevin Adams: looks like. It, it is, it's like talking about the other side. You know, we, we don't know. We have faith. We will get there, but we don't know what it looks like Exactly.

We just know that it's something different than what we deal with every day. Today.

Dr. Asia Lyon: Yeah. Dr. Jefferson would say, when people say, we will get there, he'd say, where is there? I'm like, damn, Dr. J. I don't know. But yeah, I mean this idea of, we have to close up the show, we'll be talking all day about this union idea.

But I do wanna say, I read this book one time called The [01:05:00] Miseducation of Horace Tate. Mm-hmm.

Desmond Williams: Yes. And it

Dr. Asia Lyon: talks about, have you read that book,

Desmond Williams: Dr. Walker?

Dr. Asia Lyon: Yes. Yes. And it just that idea of like black unions, teacher unions, and all the fight. Right. And then just for like NEA to just take over everything, just wipe everything out.

And that the, the fight in him, the fight in all those black educators who said like. Desegregation is going to ruin us. Right. Um, and it did.

Kevin Adams: It

Dr. Asia Lyon: did And it did.

Desmond Williams: It

Kevin Adams: did it. Hundred percent. You heard, you heard black education by desegregating schools. Yeah. I always believe that. I

Desmond Williams: know. So I know we have to go.

But there is, um, Dr. Leslie Fenwick at Howard has done a lot of work, um, along with Vanessa Sit Walker. Um, she has a, a series of articles called Jim Crow's Pink Slip that talks about, um, integration of, uh, public schools and how it hurt black teachers and black [01:06:00] administrators. And, um, yeah, it's, uh, I think it's a story that, um, we're starting to appreciate more.

Dr. Asia Lyon: Yeah.

Desmond Williams: Um, so yeah.

Dr. Asia Lyon: Yeah, yeah. Alright, well I could go into

Desmond Williams: that too, but then. Shut my lips.

Dr. Asia Lyon: I did. We'll have to invite you back to come chit chat with us. Yes, for sure. We had some on the break. We had some good discussion that we didn't get to. Um, but like we want to thank you, uh, Desmond, so much for coming on the show.

I really enjoyed it. I know Kevin's enjoyed it 'cause he invited you back, so

noise: That's right. Um, that's right.

Dr. Asia Lyon: Yes. So, um, can you just for, for our, our guests who might be driving when they hear this, spell out your website, um, so they can know where to find you. And if you're on Instagram or Facebook or something, can you put that out there and then we'll close up the show?

Desmond Williams: Sure. The, um, company website. Well, my name is Desmond Williams again. Um, sister [01:07:00] Asia. Brother Kevin. Brother Gerardo. Thank you all for having me. I, y'all know, I talk too much.

Kevin Adams: Uh, we love it. We love it.

Desmond Williams: So I, I

Kevin Adams: appreciate it. Ain't no way a black guy could talk too much.

Dr. Asia Lyon: Amen.

Kevin Adams: Unless we talk to the government.

Desmond Williams: Unless.

Come on now. Um, but I, I thank you all for having me. My website is, um, nyka.org, that's NY, um, as in New York, LIN as in Nancy, KA nyka.org. Um, you can find me on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter at ilanka, N-Y-L-I-N-K-A, and you can find me on LinkedIn at Desmond Williams. If you wanna purchase the book, the Burning House, it's on the website.

You can go to the, uh, the products tab. It's, um, what's today, the 23rd? It should be up Yes, sir. Within the next couple of hours. But, um, you can pre-order the second edition. And, um, [01:08:00] I, I delve into, um, the biggest difference between the first and the second edition is this notion of, of reading instruction.

And I take us on a history, um, lesson. Um, about the beginnings of, of African Americans not being able to read in this country.

noise: Hmm.

Desmond Williams: Um, so I'm very proud of the work. Um, I think the people who supported me when I was on the show, um, Kevin, I don't, I, I don't know how big y'all audience is, but some of my book sales on Amazon shot up.

Kevin Adams: That's what's up. That's what's up. That's what's up. So, so thank you all for that. So get the second edition people, if you haven't gotten the first, get the, get the second. Let's, let's make this happen and reach out to Lanka. Mm-hmm. And, uh, you know, let, let, let's put our money where our mouths are because we hear a lot of, you know, I, I sit a lot of, uh, every year at the beginning of school and when we come back from a break, you know, people are talking about how.

We, we are trying to, uh, get the [01:09:00] voices of black educators and, and really meet the needs of black students. And, uh, and so I think Nika, all the consulting agencies, if you aren't using the consulting agencies that you hear about on the, uh, exit interview, what are you even doing? What are you even doing?

White folks? What are y'all doing? So that's all I gotta say.

Desmond Williams: Thank you guys for having me. I appreciate those words, Kev. I, I appreciate it.

Kevin Adams: We love you. We

Desmond Williams: love you,

Kevin Adams: brother. We love you. We

Desmond Williams: love you guys too, man.

Dr. Asia Lyon: Well, that's been another wonderful episode of the exit interview, season two. Uh, hope to have you all come back again, listen to another black educator, share their experience.

Have a great evening for Asia and Kevin.

Kevin, anything. Kevin, you,

Kevin Adams: I, I froze. I, my, my internet is going bad. The sun's down, [01:10:00] dude. So you, we know how it is. We know how it in black neighborhood

Dr. Asia Lyon: retro mercury and retro. We'll, again, what, what? We're signing out. Y'all have

Kevin Adams: bad love. Bad love. Thank you.

CEO, Nylinka School Solutions

I am a career educator having spent 18 marvelous years in K-12. I launched Nylinka School Solutions because of frustration over K-12's jettisoning of Black boys. Historically, teaching Black boys is based on pathologizing them. Nylinka's support for schools focuses on helping them discover how traditional education marginalizes and disenfranchises Black boys through apparent and not so apparent means, while helping teachers mine the greatness in Black boys. Nylinka will continue to build a suite of services that supports marginalized groups (Latino males, special education students, Black girls in STEM, children in poverty, etc.) Current services include: equity audits, bias-reduction trainings, restorative practices, and building instructional equity that supports all learners.

In 2022, I published The Burning House: Educating Black Boys in Modern America. This book articulates how racism works in schools and how Black and Latino boys become disenfranchised via system oppression.