Protecting and Supporting Black Children with Mia Street

In this stirring episode of 'The Exit Interview,' Dr. Asia Lyons talks to Mia Street, a former educator who shares her challenging journey through the education system and her decision to leave due to institutional racism. Mia recounts multiple incidents where she faced racialized trauma and was placed in a system that devalued both her and her students. Despite the adversities, Mia’s spirit wasn't dampened. She transitioned to working with organizations committed to equity in education and supporting the displaced youth. The episode concludes with a poignant conversation about the systemic mistreatment of Black teachers and students, and the necessity for change within the educational landscape.

In this episode, Mia Street shares her story of working hard to protect Black children while creating her own peace within her community. Listen as Mia explores anti-blackness in the schools she supported as well as ways that she advocated for herself and the children in her care.

Resources for Black Educators Mentioned In This Episode

BH365 - https://www.blackhistory365foundation.org/

Black History 365 Education Foundation Inc. was organized exclusively for charitable and educational purposes within the meaning of section 501 (c) (3) of the IRS code of 1986. The Foundation supports Black History 365 Education’s mission in creating cutting-edge resources that invite individuals in underserved communities to become critical thinkers, compassionate listeners, fact-based, respectful communicators, and action-oriented solutionists.

Other Resources for Black Educators and Beyond

The Fire This Time: The Insurrection of American Public Education Is Being Fueled by Racism

The Colonization Of Black Women’s Work In Education

https://medium.com/@

Sister Syllabus co-authored book that examines the experiences of women of color in education across the education continuum. We are still taking interviews!

https://www.sistersyllabus.com

To connect with Mia Street:

First of all.... have you signed up for our newsletter, Black Educators, Be Well? Why wait?

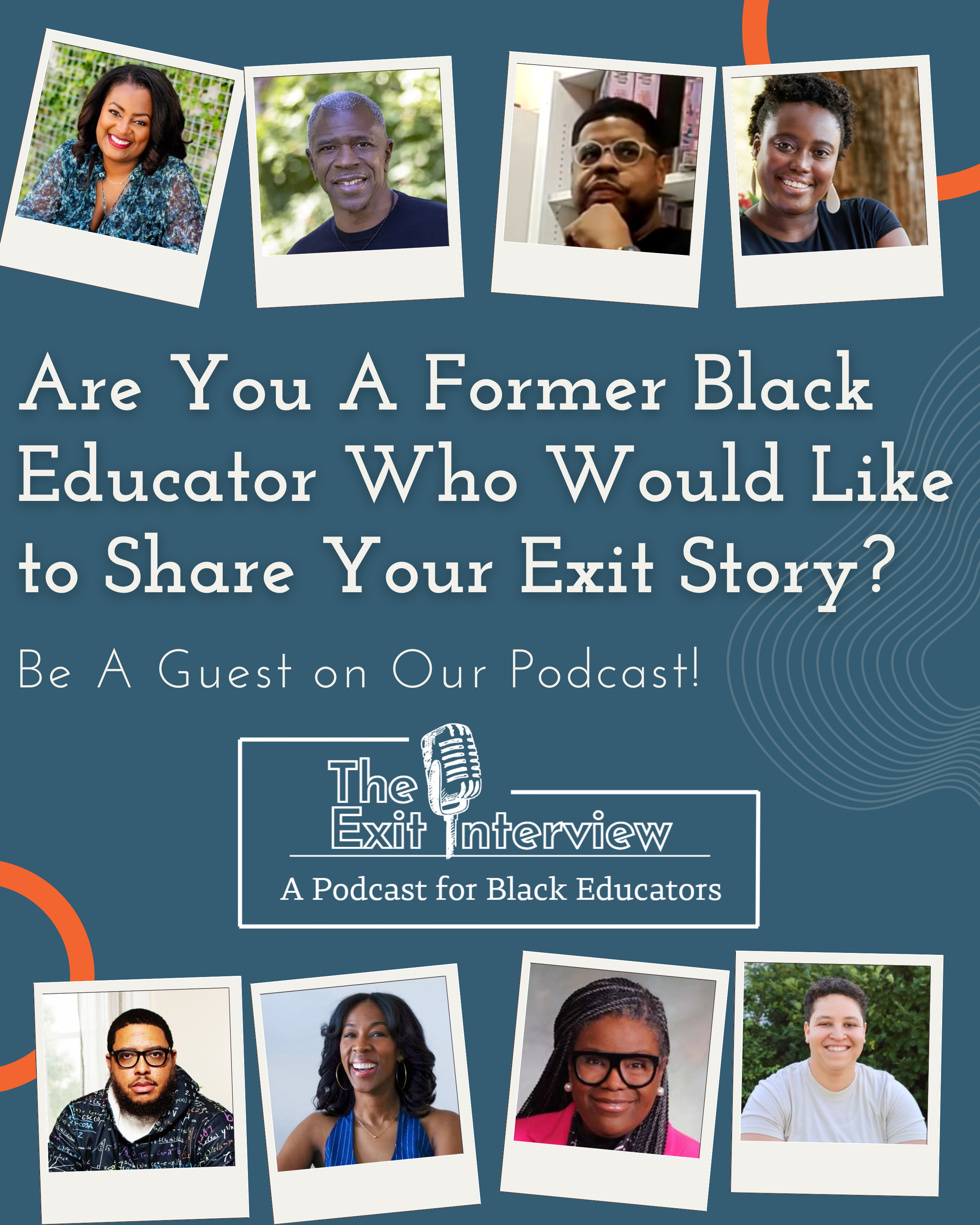

Amidst all the conversations about recruiting Black educators, where are the discussions about retention? The Exit Interview podcast was created to elevate the stories of Black educators who have been pushed out of the classroom and central office while experiencing racism-related stress and racial battle fatigue.

The Exit Interview Podcast is for current and former Black educators. It is also for school districts, teachers' unions, families, and others interested in better understanding the challenges of retaining Black people in education.

Please enjoy the episode.

Peace out,

Dr. Asia Lyons

Anti-Blackness In Our Schools with Mia Street (1)

Mia Street: [00:00:00] It's very different when you realize that the skin that you're in will impact how engagement happens. And then you have to do a work around all of that. And I think the first approach, when you're new to the, you know, education, is you might do a little yelling. You might be a little more forceful. You might be, you know, whatever.

But in my later years in the classroom, I learned that leading with love is the best way to do it.

Dr. Asia Lyons:

Amidst all of the conversation about recruiting Black educators, were other discussions about retention. The Exit Interview podcast was created to elevate the stories of Black teachers, professors, counselors, social workers, and administrators who have been pushed out of the traditional education space.

My cohost, Kevin Adams, and me, Dr. Asia Lyons, are on a mission with our guests to inform school districts, teachers unions, [00:01:00] families, students, educators, and others interested in understanding the challenges of retaining Black people in education. Welcome to The Exit Interview, a podcast for Black educators.

All right, welcome back everyone. We are on episode 29 of The Exit Interview, a podcast for Black educators. Bye. Bye. It's me, Dr. Asia Lyons, and Kevin is somewhere in Denver roaming around looking for a ride home from a football game or something. So we're just going to move on without him. Today we have a guest for our podcast, Mia Street.

So Mia and I met in Pittsburgh at the State of Black Learning Conference in August. And yeah, she sent me a message like, Hey, tell me about this podcast. And you all know. We love to have a podcast guest, so she's come on to tell us her exit interview story. And we're so excited to have you on Mia. Welcome to our show.

Mia Street:

Thank you. And thank you for doing this. This is definitely [00:02:00] a needed platform because it's a lot of this.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Yeah. A hundred thousand percent. Unfortunately, as we should, as we should. Yeah. I was at a gala last night and I saw a few of my folks who were in the lab, the school district I was in before I left.

And I just thought like, I'm just so grateful to have moved on. Right. But yeah, so I mean, we're here to tell your story, not mine. So let's start us off. Tell us about your educational background. How did you end up being an educator? What's your story?

Mia Street: Well, I come from a very long line of educators, activists.

So my grandfather on my mom's side, he almost lost his life several times. We learned recently for teaching a community in Northern Louisiana to read and to actually sign their name so they could vote. So the Klan came in and actually tried to kill him. We know for sure [00:03:00] without, you know, it being a thing that actually happened, but they pointed a gun to his head and the gun locked.

And so story I heard all my life, I didn't hear about all the other times that, uh, clan intervened. But yeah, so it's just a part of my blood to have been an educator. My aunts on both sides, both parents' sides where in education. So I grew up hearing all these stories about, you know, what it's like to be a teacher.

And I was like, oh, I'll never do that. No, that not sound like anything I wanna do. And when I got out of college, I went to college for my speech pathology degree and deaf education. So I wanted to get an education at a certain extent, but not to be a teacher. Yeah, but I didn't want to go back to school to get my C's.

So I decided to, you know, be a teacher's aide. And so that's how they, they rope you into it. Yeah. They get you in there. So I'm applying, I do the interview for [00:04:00] a teacher's aide cause I wanted to still hang out and, you know, do something light and then eventually go back to school. And so the people who interviewed me, they were like, you know what, you have, you're far beyond what we need in a teacher.

You would be so good as a special education teacher. Matter of fact, we can go ahead and get you in the certification program immediately. And I was like, Oh, okay. And then maybe a few months in, I got bit by the bug, you know? And so I was just like, yeah, I'll do this for a while. And I absolutely loved it.

I loved interacting with students. I love learning from them because I always said that the best teacher is a learner, a lifelong learner, you know, so all of those things really excited me and that's what kept me in education for a while. Yeah.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Yeah, I know, I always say this, it's never the kids, right?

Like, that's what keeps us in education. It's never. Yeah, it's never the kids. And I love to hear your story about, you said your grandfather, right? Yes.

Mia Street: Yeah. [00:05:00]

Dr. Asia Lyons: Say his name again.

Mia Street: Moses Lee Osborne.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Moses Lee Osborne. Thank you for putting him out there. So I love to hear that because I don't know if we've heard that particular story.

We do hear lots of folks saying like, Oh, my parents, my mom, my grandmother, aunts and uncles and things, but not necessarily that folks were. Educating people in their communities in these other ways outside of like a traditional classroom space. So it's always an honor to hear that folks were risking their lives and doing what they had to do to make sure that their communities were educated.

And so I appreciate him for that and taking that risk several times, um, and sacrificing his life. So when you were teaching, what grades or what ages? What were you supporting?

Mia Street: So I always wanted to teach the upper grades. So I started in ninth and 10th grade, then eventually went from nine to 12 as a special education teacher.

They put you wherever, you know what I mean? And then in Texas, they, I [00:06:00] don't know if they do this in Colorado, right? But in Texas, they reel you in even more and then they label you like highly qualified. So they justify putting you in just any place that's needed. Not that I wasn't highly qualified, but just saying.

Yeah. I knew the game. You know what I mean? I knew like, Uh huh. Who am I? How am I qualified? So, I ended up teaching English 1 through 4, IPC, so Integrated Physics and Chemistry, and then a variety of social studies, so Geography, World History, things like that. And so, I was in what they call, you know, inclusion classes, but then I also taught my own classes as well.

So our more modified classes were the ones that I got to teach. And the fun part about all that was I got to be very creative with fulfilling IEPs, right? So, you know, looking at the standards, but still being able to create curriculum that spoke to my students personally and [00:07:00] individually. That was something I actually ended up loving to do.

I thought of curriculum writing as like art and I still still able to create in that way. Yeah, so to answer your question, mostly nine through 12, I did a bid in middle school and I called a bid 'cause that's what it is, .

Dr. Asia Lyons: It's a bid wait a minute. So as a K six certified, I don't disagree, but I have to say like sixth grade, I loved.

I taught 6th graders as far as my license could go, but 7th and 8th graders can make you cry, and I'm just not interested in that.

Mia Street: It was a bid. So, I had, uh, 7th and 8th graders in reading 180. So, it's a reading intervention class. And we use the program READ 180, which had all these built in reading strategies and things like that.

My first day on this campus, campus was [00:08:00] amazing. Teachers were amazing, you know, but the kids were a challenge. So let me just tell you like this, we'll give you a little context. A few years before I got there, this is a six through eight campus, right? These kids were breaking into teachers cars, fighting.

It was. It was like, welcome to the jungle, you know what I mean? Like, you know, Joe Clark and him. And so, so, I, you know, I'm Sister Act, Sister Act 2. Yeah, and I have always taught in the suburbs because I always felt like you needed a black teacher there, you know, to be on guard in predominantly white spaces.

But this is my first time in a very, very different school environment. And this particular student challenged me on my first day. And I was like... Oh, okay. This is what we're doing. You know, we had a little check moment and I have any more, too many more problems out of him, but it was the first day. [00:09:00] Never been challenged on my first day.

He met my Tupac side.

Dr. Asia Lyons: My Tupac side has come up several times. It's interesting that you, you talk about, like, teaching in suburban areas and predominantly white institutions, I'm guessing, and I also have had that experience of teaching in mostly white spaces, the students being majority white, the teachers being majority white, and people, I felt like, when I moved here from Detroit, and I was taught for a long time, they asked, like, why did you decide to teach in that district?

And for me, it was that I moved here, did not know any districts, did not know the politics or anything. I applied because I needed a job and they were the first to call. And that was just what it was. And so I find myself, not so much anymore, but. When I was teaching, like defending my decision to teach in white spaces, as if white children and black children, brown children in those spaces didn't need black educators.

Did you have that similar experience [00:10:00] or was it something different for you?

Mia Street: I wanted to be... What I had when I was growing up. So I grew up in the suburbs, right? So I had amazing experiences with educators of color, white teachers, too, you know, I can get to the reason on that later. But the thing for me was that I knew there wasn't a me in certain places.

I knew there wasn't going to teachers who were pouring into black and brown kids and, and pushing. Them to accept who they were, who's they were and where they come from. You know what I mean? The idea of white educators only being in charge of Black and Brown children is, is concerning to me. It always has been.

So I was just like, I'm just going to do what, what I know was done for me. Yeah. That's the show up.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Yeah. I love that just to show up. Yeah, I [00:11:00] think that, I mean, that's totally necessary. And I also wonder about folks, non Black people having someone empower over them as an educator. You know, when I say power over them, I don't mean to like dominate or to control, but like really to be their educator and being used to having Black folks, specifically Black women.

In front of them, telling them, teaching them, doing all the things, supporting them, that as they get older, it's not a thing, right? So if you're in a workplace, it's not a thing, because it's like, oh yeah, I had a fourth grade teacher, my seventh grade teacher, this isn't... Versus folks who have this cognitive dissonance where they just cannot accept a Black woman being their boss, you know, when they work at, I don't know, AT& T, fill in the blank, whatever, right?

Because they've never had a Black person. who taught them growing up, who was their child care, babysitter, or worked in their ECE space. And so it really does impact folks they miss [00:12:00] out and it impacts them on the long term.

Mia Street: Yeah, and you mentioned that and what's so crazy was my first few years of teaching, I didn't understand the skin, I mean, I didn't understand it.

It wasn't until later on, I was connecting with someone. So this is probably like maybe year seven. And I was connecting with a community partner and she was just like, you know, studies show that people respond to Black women, teachers, speakers, things like that in a very different way. Where, like, if we are in front of you, we're talking, we have to command a certain amount of engagement.

Otherwise, we will have an audience that will kind of ignore you, will talk while you're talking, and all this stuff. So when she told me that, I was like, Yeah, [00:13:00] I experienced, I experienced that. Like in class, like my first few weeks of school, I feel like I'm just really having to do a lot to get a sort of respect.

And so she was mentioning those studies and then I remember I was in a training and we had one of our leadership from District of Black Women. She started to, you know, begin the training and I was just really quiet. I was like, let me see if I'm, you know, me and the other lady were crazy. Let's just, you know, and I watched how the minute she got up to speak.

People start talking, weren't engaged anymore. And I was like, and a white woman had just left the stage and it was pinstripe. You could hear it, you know? And so I was like, Oh, this is what they're talking about. So it's very different when you realize that the skin that you're in will impact how engagement happens.[00:14:00]

And then you have to do a work around all of that. And I think the first approach. When you're new to the, you know, education is you might do a little yelling, you might be a little more forceful, you might be, you know, whatever, but in my later years in the classroom, I learned that leading with love is the best way to do it.

Yeah.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Yeah, the warm demander. The warm demander. Yeah, that was me for sure. I think it was, I don't know. It was just a very firm, but loving, right? And like you said, like, I don't know. I didn't, maybe because I taught fifth grade for a little bit, and then I moved up to sixth, so I was able to kind of like flex that muscle, and I just gave children like no leeway to clown around from day one.

Because I had a reoccurring nightmare. I am not lying about this, about my classroom being out of control. And I was trying my best in my dream. And so that's always been my, my fear. [00:15:00] Exactly. You know, I get that a hundred percent. So how long did you teach before you, we will get into the question of like the whatever, like the other parts, how long were you in education?

Mia Street: So I went from 2001 until 2011 and then 2011, I got out of the classroom. For just a little bit, I stepped my toe in non profit world, helped to open up a charter school, and then did some Century 21 work, and oversaw an after school program, and things like that. And then, you know, grant funding, doing those.

And the 21st century learning experience was, like, amazing. I loved it. Absolutely loved it. It combined all of my nonprofit background and work and things I love doing in that space into like a nine to five. So you don't have the hustle of the nonprofit, you know, but grant funding went up and then I had to get back in the classroom.

So 2013, [00:16:00] 2013, 14 I went back into the classroom. I did the bid at middle school and immediately exited after that year, and then I went back into high school. So, it was a minute.

Dr. Asia Lyons: it was a minute, the on and off piece, and shout out to those folks who are guests or who listen, who are in the non profit sector, bless you, because it is the grant writing and the, those pieces.

So, then, of course, our next question is. We went back to teaching from 2014 to 2022. So tell us what was the straw? What made you decide it was time to leave education? At least in a traditional sense?

Mia Street: Yeah, and I liked how you frame that. 'cause I feel like once you're an educator, you're always an educator.

A hundred percent. Yeah. So 2014, 2018, I was in a classroom and then I ended up becoming a C C M R. So college career. [00:17:00] Military Readiness at Risk Specialist. That was a long title. Yeah. Say it one more time for us. College Career Military Readiness at Risk Specialist. Okay. So I did that for a couple of years.

And then I got promoted to the Student Services Coordinator. And that was for the district. And so I oversaw our McKinney Vento program, which is the program that helps to support children experiencing being unhoused. and then I oversaw our restorative practices and restorative centers, so there's 10 centers oversaw that.

Then I oversaw our student impact programs, which is something I collaborated with our assistant superintendent to create and then oversaw, or was a part of the equity work. So building equity in the district? Mm-hmm. , and then, oh, discipline. Discipline and then [00:18:00] also school transfers and enrollment. So it was like five things I got paid for a while.

Dr. Asia Lyons: I’m so sure.

Mia Street: So the straw that broke the camel's back. So it was a couple of them and the money was the most I ever made, but I had no life. Like I was 24, seven working. I remember this might've been like one of the first things I was like, you need to get some balance. So. I bought tickets to see Joel Coy, comedian, one of my favorite comedians.

Yeah. Yeah. And I was at work probably like six, seven o'clock at night again. And I kept thinking, I'm, I'm getting to do something. I am. Oh, no. I'm kidding. There's something I'm supposed to do. And I'm there, janitor's there. Me and him, we ended up being really cool. Cause I was there always, you know? And so walking out the building, I'm like, it's something.

I said, well, it was a Friday night. I think it was a Friday night. [00:19:00] And I was like, okay. Oh no, it was a Thursday. And I was like, well, you know, whatever. I'll figure it out. Get home, go to bed. I wake up the next morning. And I'm checking my Instagram and I see that Joe Coy was here in Dallas. I was like, I feel like I did a good job, sir, cause I wasn't working, you know, so that was like my first red flag of, this is a lot, you know what I mean?

And so then I thought, okay, you know what, find you some work balance, get you a good calendar going, keep up with your calendar, that's what's going to solve all this, you know? Sure. Yeah. Uh huh. And so then. The next thing was, so I'm overseeing McKinney Vento. There's a particular student who needed clothing.

From the district level, we handled all of the things. So we handled clothes, transportation, all this stuff for McKinney Vento babies. So I'm bringing clothes to [00:20:00] Blair Elementary. I'll never forget. We never forget. I will never forget this day. Like it happened yesterday, you know. So, I go to Blair Elementary, and keep in mind, this is also one of the campuses that's supposed to be reporting their discipline to me.

So I'm there, I'm dropping off the clothes, and I see a teacher, what I thought was a teacher. Walk a young little sweet precious. I mean, I'm not even being biased She was sweet and cute little black girl into a timeout room, you know, like I don't know this is happening Do you know what I mean? Like I don't know there's timeout rooms and I don't know at all what's going on I have zero context.

All's I see is she walks a little girl in the room and she Leans over and she says to a little girl. You're gonna learn You don't run things. Now this isn't an office, this is a front office. Why they would put timeout rooms near there, I don't know. But they're there. She says it loud enough [00:21:00] so I can hear it.

So she's down the hallway, but I can hear what she's saying to this little girl. No one in the office flinches. This is normal. And I was like, Nia, just drop off the clothes. Just drop them off. In my head, I'm like, just drop them off. And then another part of me was like, We ain't doing this shit. We not doing that.

So I went and checked on the little girl she had on Jordans. I love Jays. So, first thing I was like, Hey, I like your Jordans. What's your name? And then I'm like, you know, well, what happened? Why are you in here? And she said, cause I'm bad. And I was like, Oh. And I noticed she's writing her punishment. Her assignment was to write her name 10 times on a sheet of paper on the front side and then on the back side, from what I understand, she's supposed to explain what she did wrong.

Now, looking at all that, come back out to talk to the person that dropped off there. [00:22:00] She's talking to the secretary. So, I was like, Hey, what happened? Now, keep in mind, I have my badge on, so I'm district. You see it on my badge. I'm district. This woman looked me up and down and she was like, Who are you? I was like, My name is Mia Street.

I'm from district. You know what happens and then she's like, oh, she's always hitting people and da, da, da, da. And I was like, oh, what class is that? And she's like, oh, ABC. Now, I know because I'm special ed, coming from a special ed background. I know ABC is our autistic program. Hmm. So you put a child with autism into a timeout room, make them write their name and then on the back explain what they did, like make that make sense.

Now, I'm getting all this information, right? Yeah, I see your face. And the

Dr. Asia Lyons: audience needs to know. Can I just pause you for a second, Mia? What's interesting is that you're telling this story, and I don't know, this episode will probably [00:23:00] drop end of this month or end of September. In Denver right now, we're having a huge conversation about a school that has a timeout room that locks from the outside, that this just been discovered or whatever, after ten years.

And so I'm thinking about this and the backlash of happening in Denver while you're sharing this story. So I just want to put that out there for those who are not in Denver, that that's happening and those who are in Denver know exactly what I'm talking about. But go ahead and keep

Mia Street: sharing. Well, what I can add as a visual, you know, those waiting rooms in prisons or in jails, you know, that it was that it looked that way and it was small like a closet.

There was no window, the door was open, after, who I found out to be a teacher's aide, explained to me, you know, the child was in ABC, blah, blah, yada, yada, I was just like, okay, I'm calling you. Right. Yeah. She looked at me like, [00:24:00] a whole attitude. Oh, I'm sure. For You know, and so I go back, I'm talking to the little girl and then the principal, Jose Ramos.

It's important that we know that his name is Jose Ramos and that we're in the state of Texas.

Dr. Asia Lyons: And we're in the state of Texas, folks. Got

Mia Street: it. Okay. He comes in and he stands in between me and the girl without acknowledging me and the little girl and he's telling her that he would have appreciated her Rewriting.

Her name the last three times a little bit better. He didn't like how her penmanship seemed to have gotten a little crazy during the last three times. I said, well, I said, I think she wrote like that. Cause she's upset. Might be upset.

And he turns around, he looks at me, he looks at my badge, keep in mind, I've emailed him about three times to send his discipline reports to me, he hadn't done it yet. So y'all have history. We have [00:25:00] history at this point. He looks at my badge, looks at me and says, who are you? I was like, I'll email him. So I left.

I had to run some more clothes over to another, uh, actually an apartment. And then I came back to my office. By the time I got back to my office, Jose had called my supervisors, two black women, and had a whole story to tell about me being aggressive. You know, the angry black woman trope. And neither one of them believed what was said from my perspective.

What I was told to do Was to go make it right, and that started with an apology. Uh huh. And I'm gonna

Dr. Asia Lyons: let you say Can we, yeah, thank you. Let me sit with that for a minute. Because already, the fire's in my chest, right? So you are, two supervisors, Black women, are telling you to go back and make it right. Mm hmm.

I just want to pause for a second and say, you know, when we talk about on the exit interview, [00:26:00] racial battle fatigue, racism related stress, it's not always at the hands of white folks. I want to make that clear. And I've said this so many times, like everyone in Selma didn't march, right? Some people definitely got on buses, definitely did all, and were like, I got to get to my good job.

I got to do what I have to do. I have to, and justify harm. And so, yeah, like, Jose Ramos, we're seeing your name out here, right, and other folks in the district. This is a perfect example of folks who, non white folks, who think they're exempt, but we're talking to you too. Go ahead.

Mia Street: So, I went home and I was just like, God, you know my spirit.

You know me. I am not the person. That's going to be able to sit on, strategize, and plan. Because essentially that, to those Black women who were my [00:27:00] supervisors, their strategy, long game. At this point, I'm fighting for restorative centers so that we can reduce the amount of Black boys being sent to DAEP.

We're fighting for new equitable discipline practices. What they were telling me was, This can't be. Your fight right now, I'm not built like that. You know what I mean? I'm going to tear this down and we'll worry about everything else later. It was a hard pill to swallow, a hard thing to process. I was like, God, I don't know.

I don't know. So what ended up happening was I set up a meeting with Jose and oh, well, hold on, there's a piece that's missing in his conversation to one of my black supervisors, who she has like this brilliant mind for. Law and policy. So she was kind of the person that whenever lawsuits happen in the district.

She [00:28:00] gets on board and handles it She told me one of the things he said to her was he didn't know who I was Did not know who I was and then in the next breath told her I am for the same things me as for she's for equity and Well, I'm like, but you don't know who I'm, okay. So set up the meeting with him and I have good sense to record everything.

So I pull out my iPad. Yes, ma'am. Mm-hmm. , I pull out my iPad, I hit the record button. You know, he doesn't know this is happening in the state of Texas. It's legal to record without. You know, notifying

Dr. Asia Lyons: anybody. Colorado too, folks. If you need to know this also in Colorado, that is legal. Please CYA and use it.

Mia Street:

The first thing he starts with me is about racism and how he believes in the bootstrap kind of idea of everything. And that's what he teaches the students here at the school and. And he starts asking me all these questions. And I told him, I said, Jose, [00:29:00] I said, you know, I'm with NAACP and, you know, I am a member of ACLU.

I said, you don't want to ask me none of these questions. So what I can do is point you to some organizations that can talk to you about your beliefs in equity and education and things like that, but the conversation with me, we're not going to, you know, we not have that, you know what I mean? Cause I knew it was a setup.

I knew he wanted to pull things out of me, pull some soundbites and go back. And say whatever, but the joke was on him. I've recorded you, sir.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Okay.

Mia Street: So we ended up having this conversation where he's basically kind of spreading his little Trump ideology with me. And I'm just taking it cause I'm recording it. Cool. Say what you need to say, get it off your chest. So we now know who you are and I now know who you are to our children. So in a nutshell, that was, that was the first real straw.

Second straw was something [00:30:00] similar. I had a mom and her son come to my office, letting me know that her son was being racially bullied at the campus. He was at a predominantly Hispanic campus being called the N word. Kids were taunting him like, Oh, you know, you don't have a dad cause you're black. Like, and his dad was very present in his life, like dropping him off at school was weird.

You know, little things like that, so much so that he had suicide ideation, reported it to his counselor. His counselor did not follow up in the way that we asked counselors to, because she said that she thought he was fine. So the request of the parent and the student was to transfer him to school. So he, we were out of the transfer window and I handled.

middle school transfers. So I was like, yeah, let's transfer him. However, I want to allow [00:31:00] him to share his experience with the adults that he told and didn't respond in a way that was best. Yeah. So we did a restorative circle with his counselor, a few teachers, and the assistant principal. And then I asked my counterpart to come in.

She needed this lesson and then I asked one of my restorative specialists to lead, well both of the specialists were there to lead, uh, help lead the circle. In the circle, he shares what happened to him. He's in tears. His mom is in tears. And I'm looking at the educators and I'm just like, why is it, it just seems to not be resonating to me for them in a way that I would respond if I heard a kid that I cared about hurt.

I don't know. And so at the end of the circle, I asked everyone to say what they would have done differently, [00:32:00] essentially. Fair. Mm hmm. And a couple of the adults began with, well, if you had told us, this is what they're saying to this child, if you came to us and had told us really what was going on, and so I had to stop them.

You know, in my head, I didn't ask you about what you think he should have done. I'm asking about you. And what we don't do is charge a child to make adult decision. And so that's kind of where I was coming from. So the counselor who didn't do her job, I specifically asked her, I was like, so what would you have done differently?

And let him know, you know, this is part of atonement. Right. And so she was kind of snippy, but I wasn't catching all of the vibes. At the end of the day, that day, I get a call from the principal, and he said the counselor, white woman, went to everyone crying, and she was so distraught. Of course. Because I was forcing them to admit they [00:33:00] were wrong, and was asking them to say.

You know, they were sorry and blah, blah, blah, yadda, yadda, all the tears. My supervisor calls me in and she's like, Mia, what happened? And, uh, she was like, cause they were saying, you know, you were making them apologize. And I was like, well, number one, if you cannot apologize to a child and you're an educator,

Dr. Asia Lyons: you don't need to be in education.

Period.

Mia Street: That was straw two. Straw three.

Dr. Asia Lyons: We got a lot of straws, Mia. I know. And I'm not surprised. I'm not even Because we're educators. Yeah, because we're educators and we just keep coming back and we keep thinking we're gonna be able to change something or it'll be different or a new year, new me or whatever.

And so we just keep, some of us just keep getting kicked in the teeth. So go ahead. Share your story. We want to hear it for

Mia Street: sure. Okay. Now I'm gonna need you to buckle up on this one.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Oh, you say the best one. [00:34:00] You say the best one.

Mia Street: And this was the last one. Yeah, so buckle up. So remember, we're in the state of Texas.

All right, so this particular school district actually didn't desegregate until years after Brown versus Board. So, I'm in this kind of space. And that's important because once The assistant sup, who was the other black woman I reported to, brilliant educator, she was kind of like our strongholds in equity in the district.

She retires. So these white folks in the district was like power hungry, changing up everything. One of the things they decided to change. Was to move myself, my other black supervisor, my counterpart, who she checks Latino, uh, and then another black district leader. And they moved us all into the same hallway [00:35:00] of another building in smaller offices that had less security.

Now we're student services. And so they did all of that and we made it very clear that this looks like segregation because y'all have moved all these white people into our offices. I said, I need to leave because I'm a, if I stay, I'm going to have to figure out how to file a lawsuit. I ain't got the money.

Yeah. I ain't got the money for that. Not that I couldn't do it. Not that I, you know, but if I had stayed, I definitely would have filed a lawsuit. So what I decided to do. It was just exit strategy and yeah, so quit and the most beautiful thing about me quitting was I had some, I have an amazing village full of my own brothers and I had work lined up and things like that so it was an easier transition had I just quit when I did without a job because I [00:36:00] really didn't have anything after.

I just knew if I stayed there. It was not going to be good for anyone. So there's my exit interview.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Thank you for sharing that. I do want to say there's a couple things that in that straw three. We had a guest on our podcast, Nedra Hall, and Nedra was at a school here, and a school district here, who, they moved her into a, um, an office, and she was saying how the vent from the bathroom was right above her head in the office.

It was just like all these things, and she was like that was, that had to be it for her. And she had been a long time family liaison in the school district over 20 years. And she's like, principal changed, brought in her people, all the things you're talking about. And she just couldn't take it anymore. And I want to speak to that village too, because I haven't asked this question in a while, which is like, How did your family, how did your village respond when it was time to [00:37:00] go?

And it sounds like they were super supportive. And so I love to hear more about like what that sounded like, what that looked like for you.

Mia Street: Yeah, I had, let's see, I'm gonna name them cause everybody needs to shout out. Right. So yeah, my brother, Edwin Robinson, my brother, Leon Theodore. My cousin, Dr. Goggins, you, I think you met him at the conference.

And my sister Jasmine, they were all like, do this, leave. Whatever's next is gonna be next, you know what I mean? And so yeah, I left. And for, my first thing was, I have to let my parents know. Cause I know at some point in time I'm gonna need some help. Cause that's how my money is. You know what I mean? I have, it's not long.

Dr. Asia Lyons: And so, That's

Mia Street: so real. And I think they do that on purpose with teachers. Absolutely a way they could pay us more, but that would make us a little bit more independent. Anyway, yeah, so, uh, told my mom and my dad. [00:38:00] My dad was very clear on, I ain't got nothing for you. That's real, too. He got

Dr. Asia Lyons: a prayer. He can

Mia Street: pray for you.

He ain't got that either. He was like, I

Dr. Asia Lyons: don't know about this. You a prayer? And my

Mia Street: mom... And my mom, my mom was like, I don't understand. Yeah. You know, and this was the best money I've ever made in my life, you know? So it's like, you don't leave, you know, as black, you don't leave no good job.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Yes. Retirement pension. You got what? You got an office, a badge.

Yes. That's so real.

Mia Street: And I was like, no, y'all don't understand. This is killing me. I cannot again, walk into a building and see a little girl in a timeout room. I cannot again, be put into another space and I, or walk by this office. I'm gonna tell you this, what pissed me off the most, this was what did it, when they moved my black supervisor into the space that they moved her in.

She'd been in that district for years. She has saved them from [00:39:00] so many lawsuits, and y'all put her in the most unsafe space for her. Mm-hmm. . I was like, I can't walk by her office without wanting to do something to somebody. You know, because she doesn't deserve this. Whatever you think about her, she doesn't deserve it.

So that was kind of thing. So I couldn't do those things again. And so, Yeah, I had to leave having the plan of what is absolutely next right then at that moment didn't happen, but my brother Edwin, he is many things as an activist and whatnot, but he was the chief strategy officer for faith in Texas. And he was like, look, he said, I got something for you.

But I'm gonna need you to do five to six months, no work, and I need you to heal.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Okay, can I just say something? This right here, so what I found has been very, very interesting, and I'm so glad you said that, [00:40:00] is that I've come across women, specifically Black women, who I've talked to in community, who found me, whatever the situation, and they're talking about leaving teaching and going on to something else.

And they do that and then they find themselves just bleeding all over the place, right? Just unhealed and in this place of, am I going to get in trouble? What about this? And just not well. And so taking that not wellness to the next job and the next job and the next job because they believe that just leaving the space is enough.

No.

Mia Street: And keep in mind, we endure racialized trauma from

Dr. Asia Lyons: the womb. Mm hmm. Before. From the womb. Yeah.

Mia Street: Mm hmm. We haven't even touched the earth before. And our bodies internalize it as it being normal. That's one. We end up building some kind of tolerance to things. It still doesn't [00:41:00] mean it doesn't damage us.

We oftentimes don't even recognize that our bodies reacting in a certain way, whether it be to protect us. Or whatever it is, but our body's taking all these hits, so to your point, wherever we go next, we're bringing all that with us if we do not do the work to begin to heal. And so I was given. Uh, about five or six now, keep in mind, part of the reason why I got five or six months because they money wasn't ready.

But anyway. Thank God it's a non profit. I understand. Yes. But, I got that amount of time, and in that time, I got to go to the Gullah Islands, which was like a dream come true, and I touched that earth and that ground and learned about our ancestors, and that was just one of the most healing, I was like, this is better than therapy.

Thank[00:42:00]

And it reinvigorated me, the Carolina's just period, my whole, I did like two trips there that just it was so very close to Louisiana for me. And so I was like, yeah, this is good stuff. Red dirt always does somebody good. Got to do that. I did heal. I felt. A lot of what, that anger and that angst and that tension, I released a lot of it.

I released a lot. Some of it's still there. You know. Of course. Yeah. But I think that's partly needed. Cause. It keeps the fire going and showed up into faith in Texas, got to do create an equity plan for them because they wanted to get into activating different faith groups around equity and education.

So, did that and then now I am working with Black History 365 as the executive director for their foundation. And then I also am still working with homeless, um, population with this [00:43:00] nonprofit called RISE. And this sister who is the founder of it, her name is Renika Atkins. Mm hmm. She has a testimony. And so I'm in these black spaces doing work that I was doing in my district at a different level in a sense.

But still similar work, but in safer spaces.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Yeah, I love that. And I do want to go back. I'm going to ask another question first, but I do definitely want you to keep talking about where you are right now and the work that you're doing. So just thinking about the story that you've had, the last straws, which I'm sure if you sat down for another 20 minutes, you could think of some more, I'm sure.

Because we all could. But with that being said, with the history. your family education with knowing that people that you admire in your district were moved and all these things were happening. What do you think that school districts, unions can do, if you think that something can do to keep Black educators in school districts?

Mia Street: So, me and my colleagues actually [00:44:00] wrote about this. I'm co authoring a book called Sister Syllabus. And we are telling the stories of women of color and education, right? And all this shit we go through. Can I say shit? Can I cuss a little bit? Okay. All the shit we go through. And so when I quit, I was like, well, I'm going to go out with a bang.

Let me write out a little article, let it go viral real quick. So I did, and part of the piece that we did, we suggested some ways to keep educators of color in the space. Mm hmm. And one thing, off the top of my head, one was Believe Black Women. Yeah. Celebrate our successes by giving us ownership over the work we've done.

And another one was allowing a space to share with each other kind of what's going on. So those are a few things. Now aside from that piece, what would have kept me, if I think about it in this way, what would have kept me in [00:45:00] my district? Money talks. Yeah. So if you're going to ask me to do five, basically essentially five jobs.

You need to pay me. Then the other piece is allowing some sort of autonomy. So autonomy and money would have allowed me to stay because what ended up happening was if you pulling from my power, you're pulling from my agency. So now I'm just, I'm just a hamster in a wheel for you.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Yeah, I love that. That's so true.

I'm gonna definitely ask for the link to the article so we can put in the show notes. So that folks can take a look at that. Believe Black women, give us ownership of our work. And then affinity spaces, like being with each other. I absolutely love that. And it's interesting because a lot of school districts or people who are admin are gonna say, Oh, we do that.

We believe Black women. We give ownership of our work. We do this. [00:46:00] But no, they don't. No, they don't. Who?

Mia Street: Who doesn't? Show me. Show me where you do it. So many times I've seen my colleagues do miracle work in education. And the school might get applauded, you know what I mean, their department might get applauded, but them, no, yeah, so

Dr. Asia Lyons: no, uh uh.

Yeah, it's interesting that you're saying that, because it is a lot of, like, maybe the superintendent, maybe, I remember when, in the midst of COVID, the superintendent of the school district I left was saying how he had created this, This way to figure out if it was safe to come back to school and he had done this and he, and I was thinking, I know that you didn't sit up at night doing this, right?

I know that you did not sit up coming up with a framework or algorithm to figure out who are the people who should be really getting some of this credit, if not all of it, right? Yeah, that's super important. They're for pictures. They love to take our picture. That part. Uh, but money talks. Tell [00:47:00] us more about what you're doing now.

We started talking about it. Let's hear more

Mia Street: about it. Black History 365 is a publishing company that focuses on putting out amazing ethnic studies resources. So, I learned about them in 2019. I tried to get our district to buy their resources. They declined. But anywho. Yeah. So they have resources K through 12, which is huge, right?

Everything from storybooks to actually history books, and it's all tied to state standards. They also have an album created by a Grammy award winning producer, same as K. O., worked with Jay Z and all these other rappers. But

Dr. Asia Lyons: the,

Mia Street: listen, I listened to the work and the coolest thing is that the album takes you from ancient Africa to [00:48:00] now in a hip hop, this is so dope.

My work was BH 365 as executive director is coming in and building out and taking the work, this amazing educator, her name was Tanisha. She was actually the executive director before me. But just building out the one she's already started with fundraising and engagement and pushing the needle forward when it comes to how we.

deliver these amazing resources to different schools. So just creating a few initiatives to get that going, tapping in with people who have funding that they want to put to good use. And then the work I'm doing with RISE, I am a case manager. Our clients are oftentimes foster youth, 18 through 24. And so, you know, after the foster [00:49:00] programs and things like that, and And when they're out of the school system, they still need support.

And so that's what this program does. And it's pretty holistic. It does give a little bit of a wraparound service for them. I absolutely love it. Absolutely love it. I don't think I'm going to be, you know, around for a long time. I'm here for a good time. Yeah. Yeah. I'm here for a good time here to impact and then keep it moving.

But so far so

Dr. Asia Lyons: good. I love that. And again, we'll put all that information in the show notes as well. All right. So before I ask the last question, tell me if people want more information from about you or want to follow you on social, where can they find you?

Mia Street: They can go to key data. Ed. com. So it's K I D A D A E D.

com. And they can get everything from that website. So, Keanau is my middle name. It means Little Sister Swahili. Ooh, I love it. [00:50:00] And ed, educationdesign.

Dr. Asia Lyons: com. I love it. Thank you. And so, my favorite question to ask people, what's bringing you joy these days?

Mia Street: To be quite honest, we had a time in Pittsburgh, didn't we?

Dr. Asia Lyons: Yeah, we did. We

Mia Street: had a time. Those moments, seeing work like yours, like this podcast, you don't even understand this is like therapy. This is very therapeutic to, to share my story, to see a sister, you know, really taking out time to carve out for other folks. This is a very selfless thing you're doing. So that type of thing brings me joy.

Seeing this next generation go to work on white supremacy, love it. I was just like, some of the things I've seen, I'm just like, why do they keep messing with these kids? They will TikTok you to death, like

Dr. Asia Lyons: leave them alone. Yeah, they will find you, they will drag you, they have your social security number out [00:51:00] there.

Mia Street: Leave them alone, you know. So, all of that is bringing me joy and still. My family, my village, my parents have come around, I think, a

Dr. Asia Lyons: bit. Oh, good. Now you can get my parents to come around. We'll be good to go.

Mia Street: Let's pray on it together. I know my mom is better off. My dad, he's still working. We working, but yeah.

So those things we would do. But this time with you is so helpful and I really appreciate you for allowing me to hop on and run my mouth

Dr. Asia Lyons: a little bit. Oh yeah. I loved it. I love sharing. You know, being like a, a space for people to share their story, right? And I've said this on my podcast so many times, like I do this for Black educators.

If we hear other folks stories and we know that we can think of a different way to support youth, if we can like find whatever that is we need inside of ourselves to leave, then I've done what I need to do, right? [00:52:00] And I'm not saying that all of us who are Black educators need to run out the door. If you are treated well, or if you are holding your mind and your spirit in your body.

If you feel like you're on the path that you need to be on, great. If not, know that there's so many of us who are sharing our stories, and we're saying, yeah, we're working here, we're doing this, we're opening this thing, we're supporting youth in this way. And so, yeah, we'll always be a platform for Black educators, specifically and only because we know that our stories need to be shared.

And I've said this, I just found this out recently, here in Colorado, this is 2023, we have less than 900 Black teachers in the state. Less than 900 in the state of Colorado. Okay. Right. And it's not because of my podcast. It's because we're not treated in the ways that we should be treated. And we're not being replaced by other Black teachers, and that's just what it is.

Mia Street: I will say this my first week [00:53:00] in district administration. I left the campus. Whatever happened, whatever I saw, I can't remember, but I recall leaving, thinking they were mistreating black boys, whatever it was. Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm. , I was walking in the hallway and Dr. Wright, Dr. Shirley Wright did too bad back in the day.

I know she had to bench bow-legged now. She, you know, kind of looked like Shaka Khan, you know? Amen. Dr. Shirley Wright had to be a bad one. So anyway, you know, she's retired, like she retired last year. So I walk up to her and I'm just kind of telling her mom, Kind of venting and she looks at me calmly and she was like if you see how they treat our Children imagine how they treat us and that was the first week.

I didn't believe her until all the straws so Whatever work you're doing is God's work because our 2016

To 2020, we saw black bodies being murdered [00:54:00] on TV. It not, you know, right. And as teachers, we still showed up and then shut down happens. We still showed up. We came back, showed up 10 times harder only to be mistreated. So whatever I can do to like spread the word and get you some more interviews in, cause it's sad, but there's plenty more.

There are. Yep. Yeah. Thank you.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Yeah, of course. And thank you for being a guest. I guess that's a perfect way to wrap up our episode. And I don't know what episode number this is, but whatever it is, thank you so much for coming to our show, Mia. We really appreciate it. And thank you guests for sticking around for episode, whatever this is, of the Exit Interview, a podcast for Black educators.

We will see you next time. Have a good night, everyone. Bye. Thank you. Thanks for listening. If you enjoyed this episode of the Exit Interview, a [00:55:00] podcast for Black educators, Please help support the podcast by sharing it with others, posting on social media, and leaving a rating and review. And as always, we're looking for former Black educators to interview.

If that's you, send us a message on our website, exitinterviewpodcast. com.

BH365 Foundation Executive Director / Equity in Education Consultant and Practitioner / Author

An award winning educator, Mia Street began her career in education with Head Start and later with New Vision Learning Academy in Monroe, Louisiana. Her journey in education led her to teaching and eventually becoming a district administrator leading transformational work. Her work inside and outside of the classroom has helped to create equitable educational spaces. She currently consults with different organizations and specializes in leveraging partnerships with educational agencies and industry professionals to promote, create and increase equity in education.

Mia Street is a true pioneer when it comes to education, as she fully recognizes the significant impact it can have on people's lives. Her dedication to helping students who might otherwise be overlooked is truly admirable and her involvement in the community only adds to her value as an educator.

She currently holds the following roles:

Kidada Education Design, Founder

BH365 Foundation, Executive Director

Dallas CORE Chief Growth Officer

NAACP Texas State Education Committee Member

BTGMP, Inc Executive Director and Founder