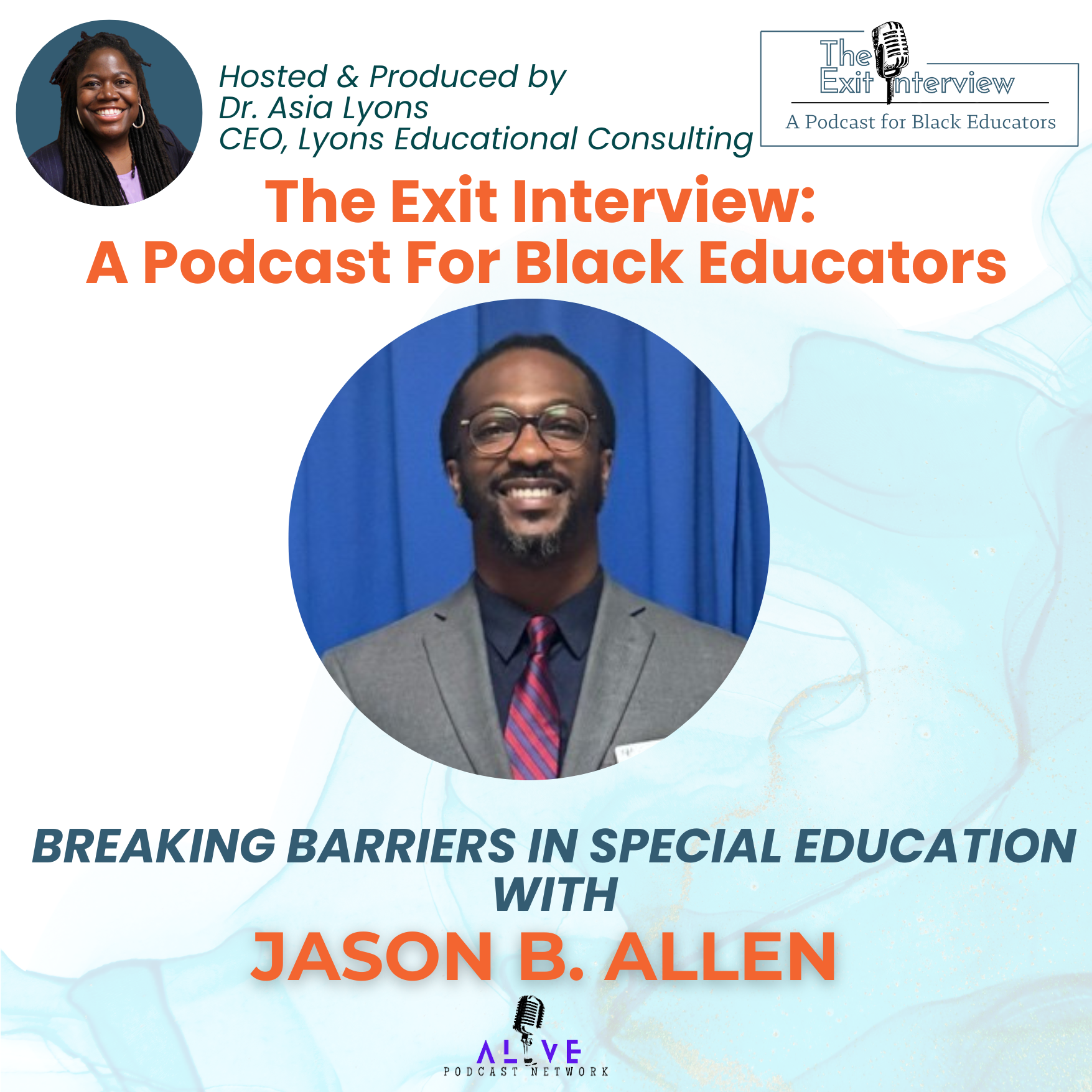

Breaking Barriers in Special Education with Jason B. Allen

In this compelling episode of The Exit Interview: A Podcast for Black Educators, host Dr. Asia Lyons interviews Jason B., an educator, activist, and policy advocate, to explore the systemic barriers faced by Black students and educators in traditional schools. Jason shares his journey from school administrator to special education teacher, highlighting his fight against discriminatory practices that unfairly place Black students in special education without adequate support. He discusses how systemic racism shapes discipline policies, the challenges Black educators encounter with certification hurdles, and the broader impact of anti-Black policies in education. Additionally, Jason talks about his shift from classroom teaching to policy work, emphasizing the importance of community-led solutions, Black educator retention, and dismantling the school-to-prison pipeline. This episode is essential listening for those committed to educational equity, policy change, and fostering environments where Black educators and students can succeed.

Podcast: The Exit Interview – A Podcast for Black Educators

Host: Dr. Asia Lyons

Guest: Jason B. Allen, Educator, Activist, Policy Leader

Episode Summary

In this powerful episode, Dr. Asia Lyons sits down with Jason B. Allen, a veteran educator, activist, and policy leader, to discuss the challenges and triumphs of Black educators in special education. Jason shares his personal journey, the legacy of education in his family, and his unwavering commitment to advocating for Black students and families. The conversation delves into systemic barriers, the importance of community engagement, and the need for policy change to support and retain Black educators. Jason also offers insights into his current work with the National Parents Union and provides practical advice on wellness and self-care for educators.

Key Topics & Segments

1. Introduction & Black History Month Reflections

- Dr. Asia welcomes listeners and introduces Jason B. Allen.

- Both share personal experiences celebrating Black History Month in Atlanta and Detroit.

- Jason highlights Atlanta’s deep civil rights legacy and year-round commitment to Black history.

2. Jason’s Journey into Education

- Jason discusses his family’s multi-generational legacy of educators and activists.

- He describes teaching as a gift and a calling, influenced by his ancestors and elders.

- Transition from administrator to special education teacher, motivated by a desire to address systemic issues directly.

3. Challenges in Special Education

- Jason recounts his experience as a special education teacher with a large caseload of Black students, many with incorrectly written IEPs.

- He shares the story of founding Georgia’s first non-suspension school and the resistance he faced from the state.

- The struggle to get recertified, including unpaid student teaching during the pandemic, and the support he received from Black women mentors.

4. Community Engagement & Family Advocacy

- Jason emphasizes the importance of building relationships with students and families, meeting them where they are.

- He discusses the fear and mistrust many Black families have toward special education systems and the need for culturally competent educators.

5. Systemic Barriers & Policy Work

- The conversation shifts to Jason’s current role in education policy with the National Parents Union.

- He explains the economic and political factors affecting Black educators and communities.

- The importance of community organizing, local elections, and policy advocacy to drive change.

6. Stereotypes, Representation, and Retention

- Jason and Dr. Asia discuss the impact of stereotypes on Black students and educators.

- The need for more Black leaders, teachers, and culturally responsive policies in schools.

- Jason’s advocacy for Black-owned charter schools and community-based educational innovation.

7. Wellness & Self-Care for Educators

- Jason shares his personal wellness practices: reading, exercise, gardening, and limiting social media.

- Advice for educators and parents on maintaining mental health and prioritizing family connections.

8. Shoutouts & Acknowledgments

- Jason gives shoutouts to family members and influential Black educators, including his cousin Ashton, his sister, his husband, and his childhood teacher Mr. Gordon.

- He highlights the importance of mentorship and community role models.

9. Resources & How to Connect

- Jason invites listeners to connect with him via social media (@ProfessorJBA or J. Burke Allen) and his website, educationalentities.com.

- Information about his books, podcasts, and speaking engagements.

10. Closing Remarks

- Dr. Asia thanks Jason for his time and insights.

- Listeners are encouraged to check out the Alive Podcast Network for more Black-hosted podcasts and to support the show.

Notable Quotes

- “Teaching is a gift. I believe it’s connected to many other gifts like administration and healing.”

- “We don’t value family and community engagement in education, and we don’t value the voices of parents.”

- “Every Black teacher is not an abolitionist teacher, and every white teacher is not racist.”

- “If those who came before me were able to endure, then I should be able to do this and make it through.”

Connect with the Guest

- Instagram/Twitter: @ProfessorJBA or J. Burke Allen

- YouTube: ETV (Educational Entities TV)

- Books: “Suitswag and Success,” “Students for Equity,” and upcoming eBooks (see website for details)

Support the Show

- Listen ad-free and discover more Black-hosted podcasts on the Alive Podcast Network.

- Share this episode with fellow educators, parents, and advocates.

First of all.... have you signed up for our newsletter, Black Educators, Be Well? Why wait?

Amidst all the conversations about recruiting Black educators, where are the discussions about retention? The Exit Interview podcast was created to elevate the stories of Black educators who have been pushed out of the classroom and central office while experiencing racism-related stress and racial battle fatigue.

The Exit Interview Podcast is for current and former Black educators. It is also for school districts, teachers' unions, families, and others interested in better understanding the challenges of retaining Black people in education.

Please enjoy the episode.

Peace out,

Dr. Asia Lyons

Episode with Jason B. Allen

Jason B. Allen: [00:00:00] We don't value family and community engagement in education, and we don't value the voices of parents. So a lot of times we aren't listening to what the everyday person is saying, because we also don't value those who we look at as less than. A lot of times we say it's lower income, but if we're more specific, it's really black.

And anyone that has the notion of you are black. And if you are Black and you are adjacent to any of the people that are behind me or adjacent to the hood, then we still look at you as less than.

Dr. Asia Lyons: In a world where the recruitment of Black educators dominates headlines, one question remains. Where are the conversations with folks who are leaving education?

Introducing The Exit Interview, a podcast dedicated to archiving the untold stories of Black folks. We have departed from traditional education spaces. I'm Dr. Asia Lyons, and I'm embarking on a mission alongside my esteemed guests. Together we shed light on the challenges, triumphs, and experiences of black educators [00:01:00] aiming to inform and empower communities, invest in understanding the crucial issue of retention and education.

Welcome to the Exit. Interview a podcast for black educators. All right, folks, welcome back to another episode of The Exe Interview, a podcast for Black educators with me, your host, Dr. Asia. It's Black History Month and we bringing it full force. My guest is Jason Allen. He's coming in with the Black History Month in the background.

If you're looking at this on YouTube, you can see it. You see, I have my books up, we're celebrating, we're doing the thing today. How are you today, Jason?

Jason B. Allen: Listen, I am super thankful to be here on the podcast, and I am amazing on this second day of Black History Month.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Yeah, I came in hard yesterday on Instagram.

Everything, I woke up and I said, it's the best, it's the best month of the year. And my daughter's like, it's Black History Month. I'm like, exactly. I saw a post on Instagram that said, don't forget to leave out milk and cookies for [00:02:00] Harriet Tubman. And instant repost. I was like, yeah, a hundred percent. Yeah.

A hundred percent. Now you're in Atlanta. What's it look like for you all for Black History Month? What kind of events and celebrations do you all have?

Jason B. Allen: It's always a celebration to be honest. Yeah. You know, as you can see, I have centered myself around a lot of our history. Maynard Jackson, the first black mayor of Atlanta.

Of course, John Lewis, Hosea Williams to my right. Coretta Scott King, Reverend Shuttlesworth, so many of our ancestors, and a lot of these are original photos or sketches from fellow colleagues, other activists, and some of my former students. And I'm sharing all that to say that in Atlanta, you know, we're a home of the civil rights movement.

It's a way of life for us. We don't really get caught up in the celebrations because we're teaching and celebrating 365. So we kick off Black History Month. You know, when it's Dr. King holiday here, so we've been teaching and, you know, [00:03:00] boycotting and protesting, but also educating and building community structures and programs for our people.

So that's the Atlanta way.

Dr. Asia Lyons: I love that. I grew up in Detroit, you know, until I was 22, 23 years old and the same, like Detroit was, it's just what it was, black history. We have poster, all the things, plays and no matter what time of year it was, and then moving out here to Denver. And people know it's a whole different game, right?

Jason B. Allen: It is. I've visited Denver frequently, I would say in a past life, it was, you know, kind of like a second home. But Detroit, you know, I'm looking at one of my favorite books, pages from A Black Radical's Notebook. The Boggs family and so many of the activists there and how Detroit was a game changer. And we saw how much like Tulsa, much like other cities across the U.

- that had, you know, strong political power of black citizens, strong, you know, home ownership, strong family [00:04:00] units, strong schools, strong financial institutions, they were strong in the U. S. What? Blown up, set on fire, riots,

Dr. Asia Lyons: white flight, all that.

Jason B. Allen: Yeah, and so when you mentioned growing up in Detroit and your stint there, I immediately looked to pages from a Black Radicals notebook, which, you know, again, as a long time educator, that is something that I've used to teach the next generation about how our ancestors

Dr. Asia Lyons: Yeah, Grace Lee Boggs I learned about after I came out here to Denver and just saw a documentary a long time ago now about her life and her husband and their writings and we have lots to learn continually, right?

Jason B. Allen: Yes.

Dr. Asia Lyons: And we could get talk about black history, black present all day, but. We'll get to probably some more of that because this is going to be a fantastic podcast, I have a feeling. So first question, I ran into you at BMEC, the Black Male Educator Convening, [00:05:00] and you started to tell me about your journey into education, so now it's time for my audience to hear.

Tell me about your journey into education. What helped you decide, or who helped you decide to become an educator, and what was that journey like for you?

Jason B. Allen: Awesome, well first, I have to Pay homage to my ancestors and also my elders. I come from a family of educators and activists. We trace our lineage back to in the U S as far as 1865.

And we also had been able to connect our roots back to Africa, to West Africa. And ironically, you know, coming from a lineage of people who fought for, you know, civil and human rights. And so I would say that it's a gift. I believe that teaching is a gift. I also think that it's connected to many other gifts like the gift of administration, the gift of healing, and that's how I look at my 20 years now in education as, you know, doing education policy work now for the last two years, but coming out of the classroom as a special [00:06:00] education literacy And you know, again, my mother, my sister's cousins, grandfathers, grandparents, my great aunt, who was the first to have a doctorial degree in our family, who was also a Delta, you know, we believe in education being the passport to freedom and in order to sustain that, it's economics and that is the premise of how I came into, you know, education when I look at some of the photos, Behind me, there's a picture signed by Nelson Mandela that came from my great aunt, who was an educator and a history professor, you know, original photos from and of civil rights leaders and their impact to our work.

And so that is. My journey into education and what kept me in education. Now that's a whole nother question and a whole nother story for these last 20 years.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Well, then go ahead and answer that question then, because that's what we [00:07:00] want to know. Yeah, it makes sense what you're saying, right? A legacy of teachers, of healers, of circle keepers.

But what kept you in education for all that time? In the traditional education space, I should say.

Jason B. Allen: I believe the children are our future, you know, I, first of all, Whitney Houston is the voice and I love that song, but it also is the message and, you know, believing that the children are our future means that we know that we have to make sacrifices.

We talk about, you know, this previous election and, you know, looking at sustainability, people don't realize the sacrifices that people made to say, hey, I want to support. This presidential candidate, I may not even be a Democrat, but I believe in what, you know, she's doing. And I also believe in the future.

There are a lot of people who will say, yes, black lives matter. And I'm all for the movement and I'm all for the people. But I have been that teacher that has said, Oh, you want to discriminate against my students. And I have battled to say to Georgia so much so [00:08:00] that when I helped to start the first non suspension school in Georgia, which again, we are in the Bible Belt, we're in the South.

The school to prison pipeline is real. It is the new slave plan, right? That's their billion dollar industry of third grade data that they pull to say, how many black boys, how many black children can we imprison and how much money can we make over time? And so when you consciously make a decision to fight against that, you have to be willing to lose your job.

You have to be willing to lose your Certificate of people will say, well, you should have been smarter about what you did and how you did it. Well, I'm sharing this because in 20 years, I'm now in a space where nationally I am meeting with people from the Department of Education to global affairs entities to so many different people in the political space.

impacting policies, but I've also been a district administrator, a school leader. I've been a team lead, [00:09:00] and I've also lost my job because I said, I'm going to stand up for children who have disabilities, especially black boys. I'm going to stand up against us, you know, suspending and pushing out black and brown children when we haven't trained our teachers on how to, yes, let's be restorative, but let's also be respectful.

And so I'm sharing that because people will say, well, how did you get to where you are? And it was a trusting in God. And what I knew my calling was for this, right. And then to making sure that I am standing up for what I know is right. I want my very first essay contest in fifth grade, the year that my great grandfather passed.

And the essay contest was around standing up for what you know is right. My father and my grandfather who passed that year. Help me with that essay and that's what has sustained me still from fifth grade as a 10 year old to now being in my 40s in my 20th [00:10:00] year in education, I can say that I have always stood up for what is right for Children, especially black Children, even if it cost me that job, even if it cost me a promotion, I did it because it was a sacrifice and I knew that the Children who I sacrifice for we're going to go out and make a difference.

Dr. Asia Lyons: So let me ask you a question and we can totally 100 percent get into being like fired from places and being pushed out because that's something that I think the two of us have in common. I wasn't necessarily fired, but you know, when it's time to go.

Jason B. Allen: I know. Oh yeah. I know exactly what you're saying.

Yeah. It shows up in different ways that people do need to know that.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Yeah. I want 100 percent get into that question. I do want to know, you know, people come on and they go into education, teaching third grade, fifth grade, high school language arts. Yeah. You know, English, all the things for you. Why special education?

Jason B. Allen: Oh, that's a good question. So let me tell you, I'm doing exceptional and that is really what helped me to connect with my students [00:11:00] and quick story. I was a school administrator. I was like, I'm not suspending another kid. I started a program, a restorative program. I have another book that's coming out around students for equity.

That was birthed out of. Me being an administrator, and I was like, this is going to be the A team, right? And basically, it became a group of predominantly Black boys that kept getting put out of class. And so, parents, people who wanted to fund our schools, program, the staff, everybody trying to meet with the school leader, right?

But now I have a whole room outside of my office full of students, and now, instead of me being in my office with the door closed, I'm in this large room doing what? I'm teaching. And so that is what made me leave administration. I know people are like, what, you left that good check. You left that position to go and teach.

I sure did. Because I said, I want to go to where the problem is to fix it.

Dr. Asia Lyons: I'm glad that you're clarifying that. Cause in my mind, I'm like, is he telling [00:12:00] the story forward or backward? And so you're saying you were an admin first and then become a special education teacher.

Jason B. Allen: Yes. I love being a school leader and went to teach.

Special education. And okay, that is how I ended up being recruited. So I went back into the system as a teacher and I was I know how the system works. I've been all the way up. Now I'm coming back down and I was able to make change. I was teaching special education. I was in a Saturday Academy, brilliant black woman, wife, mother, just passed me teaching.

Happened to me before, right? Somebody just saw me teaching and was like, Hey, I was like, I'm in Douglas County teaching special education. I have 115 students on my caseload. 88 of them were black students. The majority of their IEPs were incorrect. So I was sharing my story and I was like, here's some of my lessons that I did to help get my students ready.

You know what I'm saying? For high school. That's how I got recruited to become the founding special [00:13:00] education and lead teacher at Seven Pillars Career Academy, which was the state of Georgia's first and only non suspension school. And so when I went there, the state was like, what do you mean that you have this number of Black kids?

Testing out a special education and being tested in to gifted because I'm dual exception. So I am gifted and talented, but I also had a specific learning disability. And when I share my story with my students and they were like Professor JBA, I became Professor JBA from a lesson that I was teaching.

When my student connected to Stan Lee because I love comic books, the X Men, right? And I was like, we actually are all X Men. And so my students were like, you are our Professor JBA. That was like almost 15 years ago that I became Professor JBA from that lesson teaching students. And I wasn't even a special education teacher.

That is when I was an admin. In the 18, that's how I became professor [00:14:00] JBA. And so taking that to a non suspension school, where now there is no putting you out, we are going to work through this and build through this, those children, one of my first Afro Latina students, one of my first. Latino students, one of my first black students that was dual exceptional and had a double hearing aid came out of special education programs in the state of Georgia said, we got to get rid of him.

He is certified to teach, but he's not certified to teach special education. So they took my certificate after they found out that, oh, he is getting these kids. He's taking money out of my pocket. So we need to 86 him.

Dr. Asia Lyons: You told me this is a part of the story that we talked about at BMEC. Yes. It's just like going back and being recertified.

And I do want the audience to hear this. So please share that story.

Jason B. Allen: Yeah. So basically, when the state of Georgia said, Oh, this, you mean to tell me you have this amount of kids? They thought that we had cheated. They thought that it was false. Every time they tested my children, [00:15:00] boom, they kept doing it because it was skill set.

They had the skill set. You can't take that once I have it, right? They had the skill set. They kept doing it. They was like, Eh, something. No, no, no, no. We got to find a way to stop this. They found a way. They basically were like, Oh, you are certified to teach, but you're not certified to teach special education.

So they had all these different pathways. They blocked me in every pathway. They were like, you're going to have to go through a traditional program. I said, okay, well, I wasn't planning on going back to school, but I will. Then I had a university, university in Virginia that said, Hey, we'll accept you and give you a full ride, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah.

But they said it was a black woman. Again, I got to shout out black women because at every turn I had a black male mentor, but I had a black woman that was an angel that was like, Hey, I see them trying to do this. Let me turn it around for you. And so basically the university in Virginia was like, we don't want to accept you because you will go into debt and you still won't get your certification because the state of Georgia is [00:16:00] not honoring your years of student teaching.

Now, mind you, I had already been teaching. In the classroom for over 11 years. This was my 14th year in education, 14th year. And they made me go back and do student teaching. So now we're in the middle of the pandemic for two years. I did not work. I did student teaching. And there was another Black lady at the state who is now retired that said, Hey, I see your situation, but this is what I'm going to do.

Stay connected to your mail. Two days later, I got a certified letter in the mail that said, You are doing student placement. And it was at my school. So I went back to do student teaching at my school for two years to see my students from sixth grade to eighth grade. Complete middle school transition out of special education.

I did not get paid a dime. I couldn't get paid because I had to do student teaching. And so I'm sharing that sacrifice because my students were able to promote. You can see my work on my [00:17:00] website, students for equity. These are all students that have learning disabilities that were told that you will not.

Make it out of middle school, you will not graduate high school and all of them are graduating a year early this year in May of 2025. And that's the story. That's it. That's everything.

Dr. Asia Lyons: No, it's not because you said something. We were at the conference that I want you to talk about. But before I ask this question.

Hearing your story is really interesting because I've had folks come on Dr. Adrian whose episode probably is like recorded right before yours. She was a principal for a very long time, administrator, and then went to become a coach. And you're saying, again, administrator, special education teacher, just be solely off of like this is a gift.

This is something that you were born into, like this is what you were meant to do because of your own being twice exceptional and then the skill you have, but you also mentioned being in school student teaching and not being paid for that. What was the response [00:18:00] from your community and your family specifically?

when you shared this journey and all the things you were going through trying to get back into the classroom to support your students?

Jason B. Allen: You know, that's a great question. You know, supportive, you know, prayerful, reflect on even, you know, my dad is one of my mentors and his thoughts on, okay, this is what you have to do, then let's do it.

But now, so how do we help keep the lights on? And so, you know, it was opportunities and. Things that, you know, came across again, I think about those two years of going through school and, you know, different contracts and people were, you know, my small business was thriving and that helped me now it's not thriving right now, I'm building it back.

But what I needed during that time came and I just really think having seen my great grandparents, especially my dad's grandmother, who lived to be 115 years old, she was a descendant of. Slaves and knowing that history of our family and how we have been able to [00:19:00] persevere and overcome. I think about that in circumstances.

If those who came before me were able to endure it, and this is my cross to bear and Hey, let me bear it and, you know, go through it so that those who come after me can say, Hey, if they did it and then that group did it and he did it, then I should be able to do this and make it through.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Yeah, I love that and I want to say also that you talked about you had a several students more than half of your students IEPs written incorrectly.

Jason B. Allen: Oh, yes.

Dr. Asia Lyons: And I want to go back and talk about that for a moment because I know that folks heard that and I think that's one of the biggest fears of folks of color when putting our children into special education systems, getting them an IEP or in 504. Is that they're thrown in, it's not honored, it's incorrect.

That's good, yes. All these different things, right, things like services are missing from their IEP. There's a lot of fear, right? And rightfully so. And [00:20:00] so, can you tell me about that particular experience and what it was like talking to families about coming back in, doing that re engagement with the IEP, and having those conversations, and trying to fix those things.

What was that like for you? And for the families, too?

Jason B. Allen: Let me say that some of that was official, some of it was unofficial. I wasn't going to wait on the system that had already failed these children and families to say, Oh. You know, we did this wrong. I made sure that I a built relationships with my students.

And I also was in community. So I was like, Hey, okay, listen, school is out. Listen, your dad is still up at the tire shop. Your mom is still up, you know, at the bank, your grandmother is still at the Walmart. I also spent time in community meeting families where they weren't was like, listen, can you come up to the school?

You can't come up to the school. I need five minutes. My dad is the only non educator, even though I say he is an educator in our family. He's a business owner and he's an entrepreneur. So I know how to market and sell baby. You say I need [00:21:00] five minutes. You say three. Okay. Three minutes. Here's what we're going to do and here's what it is.

And I'm very intentional about, I don't want to waste your time because it's already been wasted, but here's what I've seen. And this is where we can get your child. I have former students who work for the city of Douglasville, the city of Atlanta, the city of South Fulton, you know, Duluth, et cetera, so forth, and they have good government jobs.

And guess what these brothers can do. They can take care of their kids. And so for me. That is gratifying that I have students that listen to my lessons and are good husbands and are good men to their wives or their spouses and are good fathers to their children. That is, they may not be doctors, they may not be lawyers, but let me tell you what they are.

Doing so for me, that is a huge win for us. I have former students that are teachers that were like, I went back to teach brother, because you reached me. [00:22:00] I'd never had another teacher like you, but every turn I thought about what I learned from you in middle school, in high school. And I was like, that stuff rings true.

And so that is why I did what I did. With my 20 years in education and also thinking about how the IEPs to go back to the original question and even the services are not provided. I also want to make this very clear. A lot of my counterparts were white and they did this. I don't think it was purposeful.

A lot of them make assumptions. We are a product of our society. We assume that something is wrong with black children because. This is what society, this is also what research has taught us. And I want to say that when I went to get my degree in special education, I realized that we don't have people on the state level who are training teachers who understand that there are different nuances in education that impact the way that children learn.

And so I had my [00:23:00] very first and only Black professor who was a woman. And that was my only class that I felt seen that I felt like this is really something that's going to impact all of the children, not just some or a few of my students, but this is something that will impact. All of my students and it was the first class where I did not have to go and buy extra resources because my professor was intentional about let me make sure that I provided something for non English speaking, you know, students and educators who are serving them and educators who have Muslim or Hindu or spiritualist children in their classrooms and their religion.

May say that, Oh, because you learn in this way, it's demonic or it's bad, or you're different. And how can I help this teacher impact this child who was also dealing with social, emotional trauma, because you have a speech impediment and culturally we're saying that, Oh, that's [00:24:00] of the devil. Maybe it's a speech impediment.

You could grow out of it. If your family and your culture wasn't telling you that you are demonic, but you can't shake that. But there's no research, there's no support for teachers who don't have that coming through programs because we are not there. And so having to go back in and correct those IEPs and making sure the services align was crucial because I not only found myself the only person in my building, but even my special education coordinator.

Who oftentimes are not people of color who are maybe white women do not have that training and do not know that, oh, this IEP looks good, but it is not matching up to the needs of the whole child. And I wanted to make sure that I put that in the atmosphere because even black educators who are not studying and who have shown themselves to be approved still missed the mark.

With our children thinking that, Oh, that's a hood thing, but you didn't grow up in the hood, so you [00:25:00] don't even understand the dynamics of the hood. So just because you're black doesn't mean that you understand all black children and you definitely understand the nuances of. The hood are living in lower economic communities.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Yeah, it's interesting that you said that because I think about being, again, raised in the city of Detroit and then coming out here to Denver and the folks, the educators that I've black, white or otherwise who I've taught with, I can't imagine them teaching in Detroit public schools. And vice versa, really, Detroit Public Schools folks coming out to Denver.

And so my next question is, you were doing that work and it sounds beautiful, but you're not doing that now. So what was the situation or what was the thing that caused you to shift out of the traditional education space?

Jason B. Allen: That's a great question. The school that I planned on returning to and wanting to work at thought that [00:26:00] they had the money and they didn't, to be honest, and very upfront.

I mean, no tea, no shade to them, but that is how the charter world works. And that's why I'm a huge advocate for black and brown owned charter schools that connect with HBCUs, that connect with churches because it economically gives back to us. Like overtime, just like that, we see the dollars coming back into our community immediately because the employees live in the community, the children in the community are being served, we need after school programming, we need nonprofits that we can give small contracts to who are in the community.

So, That was the situation as to why I did not return back. And it was already like right at the start of the year. So any positions or any, like, you know, everybody's trying to grab what they can, the best of the best. And it was like, Oh, okay. It was stuck. And the national parents union came along and said, Hey, I think that you may be available.

You would be awesome [00:27:00] with, you know, helping us organize and I can organize in my sleep because I come from a family of organizers and activists. And so that's what placed me in the education policy space is much more. So now. In being the partnership director, really, you know, working with the United Nations and with the U.

- Department of Education, even under the current administration, but also national organizations that are influencing, impacting policy, research, innovation, and education, a lot of the spaces that I'm in now. I am the only black and you can check off the list of however long it may go, but I am the only person in that space.

And so I am definitely missing teaching, but also. Excited about this new exploration and then still encouraging people to say innovation and education does look like if the best teachers are coaches and administrators, why are they not running the class? I believe in that. I would [00:28:00] love to see a school where I'm the executive director.

I'm the school principal. I'm the nurse. I would love to, you know, see the nurse teaching a class on hygiene, health and wellness. Like I just, where we create that. That culture and also having been a district administrator with innovation, looking at how do I build culture in my school, if my school nurse and my bus drivers, if my, you know, educational staff and my teachers are having to work two or three additional jobs, they're not coming to work at 100%.

And I need my staff to come in at 100%. So if there's a way for Okay. Us to add more classes and you know, you get in the extra 500 a month because you teach this one class a day, but it's every day and we're seeing gains here. How do we make those things happen? And I will also say this, you know, on your podcast as a district administrator, I have also seen [00:29:00] the equity conversations of why do the white schools have this?

Well, let me give everybody this for free. All right. Their communities are much more engaged in a different political and financial way, and they create the positions that they need, and they fund the work of their teachers and what their teachers need outside of what the district provides. So I want to say that and also say go to educationalentities.

com and book me if you want to know how to build that for your school, because we do need. More of that. And I'm talking about locally operated or what some people may say traditional public schools were doing this. This was not just charter schools that were doing this. Traditional public schools have and are doing this.

And I would love to see more black leaders in the forefront of that type of innovation doing what's needed for our children.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Yeah, I think that's a perfect segue to the next question I'm asking [00:30:00] because you're talking about desire to see Black leaders, Black educators in these spaces. My next question is, like, what do you believe that schools, districts, unions can do to keep Black educators, whether that be And I say educators, I say paraprofessionals, nurses, school psychs, principals.

What do you think that they could do to retain, and when I'm saying retain, I mean us being well as, you know, not just there, but being a thriving. What do you think they can do to keep us so that we're thriving and we're supporting our communities the way that you talk about?

Jason B. Allen: Yes, I love that. Well, I would say first community has to be accountable.

Let's be honest. Our current president is saying I want to push more power back to the states. Well, that's going to disenfranchise even more people because what I know for a fact, especially over the last 10 years, and what I've been teaching my students within this last decade is that local elections have poor voter turnout, right?

So how do we retain teachers? How do we do more for [00:31:00] teachers? You need school board members, like. For example, in Atlanta, Georgia, Shibby Brooks, who was the first active teacher On the school board who is actually teaching in the classroom and it's on the school board. Well, how did that happen? It took community organizers, right?

Partners like equity and education and the Georgia, you know, National Parents Union team and Lilly's Foundation and other people to come together and say, Hey, we want to put the funding behind this candidate and get this candidate on the school board. Right? And so we had grandparents. Put in the side, they, you know, 2 or maybe they 5.

We had children put in the side, the coins and they piggy bank, whether it's the, you know, digital or in like live, right? We have people engaged in all ways. However, you want it to digital currency. However, you want it to be connected. We connect the people. This brother got on the school board, did what he needed to do to galvanize the [00:32:00] school board and said, Hey, we're going to change teacher salaries.

Well, that was the biggest change in a district in Georgia. And what happened after that, the other Metro Atlanta district, which are 41 said, Hey, they're getting all the good teachers. Cause all of the good teachers are wanting to leave us and go there. We need to change what our teacher pay scale. So now this year, when we go to the Capitol on February 27th in black history month, we are bringing together over 300 black fathers.

Teachers and educators to the Capitol to advocate for this. Now I am doing a shameless plug for our annual day at the Capitol, but I also am saying that this is our fifth annual event at the Capitol. It's the only one in the state of Georgia, and it came from my students. Right. My special education class, the one that we overlook and think that these students get my students in a special education class.

I want to make sure that I stress [00:33:00] that because these were students who were not passing the standardized test and who were not on the principal's list and who were not like your, you know, spell and be winners. But when I said, what is the problem that you want to fix and what is something that you want to see?

And one of my students who actually is now on the principal's list. Said that I want to see more teachers like you. And so I said, let's research this. My students, they did the research. They found that there is not a day that acknowledges Black fathers or Black teachers or Black male teachers like that at the Capitol.

And we created that with the help of our locally elected official at the time. And we started this day to honor Black fathers and teachers and community leaders at the Capitol and to advocate for more. Black teachers in our state. So it's important because if our students are not involved in the change, if they're not involved in innovation, then we just going to continue having great conversations like this, right?

[00:34:00] And everybody's talking, but how are we strategically implementing what we know that Douglas, what we know that Harriet, what we know that John Lewis and Nelson Mandela, like what we know these people did. How are we actually going to do that to move the next generation forward?

Dr. Asia Lyons: Yeah, this is really important policy.

So, we had on last season, Jalissa Evans, and she's out of California. Okay. For the Black Educators Advocates Network, and she also talked about policy change as the way to move the needle, right? Her work is on, and her work of her organization and the community. Is on shining a light on anti blackness in education in California.

Jason B. Allen: Oh, yes. That's big out there.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Yeah. And specifically like, okay, there's anti blackness. Now, what are we going to do about that? Because I think that people conflate teacher of color with black teacher as if that's the same thing.

Jason B. Allen: Yes, that's good. You drop. That's good. It's good.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Thank you. Thank you. And [00:35:00] so she has been one every time people talk about policy.

I've mentioned her and the work that they're doing out there because you're right. It is coming from community and for her, it was the educators that were in her community when she was building coalition space to say like, what's the issue and the issue is. Yeah, there are teachers of color teaching children, but they're really saying Browns teachers.

And there's not enough Black educators, and a lot of them in that situation in California are being pushed out by Brown folks. Yeah. Brown parents, Brown colleagues, Brown principals. And that conversation is not happening the way that it should. So I'm glad you're saying that. And so in that same vein, My next question is, tell us, and you've kind of hinted to this, what are you doing now?

Where are you working? Because this is pretty fresh, it sounds like, that you, you're not just in the National Parents Union, like in the last month or so, but it's fairly new. Oh yeah, it's still fairly new. So tell us what you're doing, tell us all the work. [00:36:00] Yes, because it was the

Jason B. Allen: school year. So tell us. So now, currently, I'm with the National Parents Union.

We are the independent, united voice of modern American families. We create and implement policies that positively impact, right? Because you can create policies, but they can be detrimental to masses and beneficial to very small percentage. So we create and implement policies that positively impact. The lives of modern American families, and it's not just centered on innovation and education.

We also look at policies that impact economic mobility, because these were things that American families had been telling us way before. Let me just say this, Black America, I want you to hear this. Modern American families were talking about economics way before the campaign. Okay. So I just want to make sure.

That the Democrats and everyone else hears that that was a concern for modern American families before we have the data that proves that. But I also want to highlight this. We don't [00:37:00] value family and community engagement in education, and we don't value the voices of parents. So a lot of times we aren't listening.

To what the everyday person is saying, because we also don't value those who we look at as less than. A lot of times we say it's lower income, but if we're more specific, it's really black and anyone that has the notion of you are black. And if you are black and you are adjacent to any of the people that are behind me or adjacent to the hood, then we still look at you as less than.

So I also wanted to just, you got to pause, pause there, highlight that in the policy world.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Yeah. I'm sorry, Jace. I have to say this because you on the roll and I, I said, I know I saw your hand. That's

Jason B. Allen: why I was like,

Dr. Asia Lyons: listen, the way that I have sat and watch white teachers be so afraid of black parents at conferences.

And not tell their parents or the grandparents, whomever, family members that this is a challenge. This is what's happening because [00:38:00] that white educator is so afraid of a family has done nothing to them. And so they're keeping them from supporting their student with a family is right there at conferences.

Right. So when you say that is so, so true and I've seen it so many times and think. You afraid of black people, you were afraid that they're going to jump across the table or yell at you and all these things based on some made up experience in your mind and it hurts our communities and our families. So I just had to pause you and say that folks y'all have to know that.

Jason B. Allen: Well, I want to pause you and say that that is a great point and having a lot of. Okay, let me say this. It's important for us to, yes, I am very pro HBCU. I did not go to an HBCU. I went to a predominantly white institution. And that helped me to learn white people a little bit differently. Because we do go into situations a lot of times that white people are the enemy.

[00:39:00] It's white and it's black. And we draw those lines. And I'm sharing this because it connects to how it impacts policy. It connects to the stereotypes. And so stereotypes, that is the Suitswag and Success, my very first book. I wrote this book to address the negative stereotypes of Black men and Black boys.

It connects, this is my 25th year of advocating for male engagement. My program that my former professor and mentor, Dr. Saeed Sewell, and one of my best friends, Terrell. Cleveland started at the University of West Georgia, it's called black males with initiative right on the, at the cusp of, you know, President Bush saying, Hey, we need these special initiatives to really kind of cleaned up some areas where we messed up.

Right. And so from that research and looking at how we have to advocate for ourselves in different spaces, our. Biggest barrier are the stereotypes because there is a good [00:40:00] number of white people, I would say that now there's a smaller number of them that is like 10 percent of them that are like Jimmy Carter, knowing him and his family personally.

That's a very, if we can get 30%, we will really make change in this country, but we don't have 30 percent of white people who are like Jimmy Carter. I'm just being honest because we, this is the platform to be honest. And I feel like this is helpful for people to know you've got to be able to find a Jimmy Carter's in your community because it's a diamond in the rough.

All white people are not Jimmy Carter. Please don't that they're not. That there's 10 percent of them that are, but it's 30 percent of them that really do care about humanity. They care about other people and they are people who I have worked with that a lot of times are fearful. They are, they're fearful of black families because They too have been taught, they have been conditioned to think that if black people I can control you if I'm nice to you and I'm, you know, kind of [00:41:00] pacifying you in a sense I don't want to be too truthful with you because if I say girl, you know that this system is really setting up your child.

I don't have security near me. I don't have anybody there in case you act out because they have been told that we are instable that not that it's like a bad thing. It is a bad thing because it's a negative stereotype. It wasn't maliciously taught. That's a part of their. You know their culture and I had to accept that and then I had to figure out ways to work around that because is it my responsibility to educate you not per se, but it is my responsibility to make sure that I amplify the stories.

And amplify the personas of black people that I need for you to be connected to so you understand the human side of us and you can break down those stereotypes. And I wanted to just give some time to that because on a psychological level, I know that we think about stereotypes and bullying like, oh, you know, that's par for the course, right?

[00:42:00] But. These are major things because how my psyche thinks of you is how my heart and my spirit are going to convey those thoughts and my interactions to you. And so giving white people a little bit of grace, but also understanding that a lot of times they are going by what they have been taught, which is embedded in what racism, you know, all of those things.

And so we have to. Teach them and we also have to reteach ourselves.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Yeah, that's interesting because I'm a person who and people who know me in community here in Denver and beyond, you know, they'll ask like, well, this situation happened. What would you have said? And I'm very much a person who has. No interest in trying to convince white people of my humanity or the humanity of other folks because it's like if you can't read the same book that I've read, if you can't, like, watch the same lecture or be in the same space, then how, like, who am I to believe that I'm going to be the one who's going to change your [00:43:00] mind?

And at the same time, I can see what you're saying because our students, in the meantime, are experiencing harm if someone. Doesn't at least attempt to, I don't know, shine light on some of the ignorance they have that they're maybe unaware of. So like, that's always like a push pull for me because I know that there are lots of people who rightfully sort of like, yes, I see the reason why this needs to happen.

I'm willing to do that work. I can see the outcome being positive if this goes well. And then I see also people like myself who are like, Yes, I agree, but it can't be me,

Jason B. Allen: right? No, that is awesome and honest to say that it's not for everyone. That's why I'm so big on storytelling because your story can impact people in different ways.

Everybody is not going to do it the way that you do it, but they can hear something. You said, you know, take it and say, I can improve my process. I can, you know, improve or change my approach. And I think that that is also. Important because we do still need the parents that are going to come in [00:44:00] and, you know, flip tables over and say, Oh, you did this wrong, but my child, but we also need parents to say, listen, Hey, at the end of the day, I'm tired.

I know you're tired. This was done in a manner and I needed to be better for my child. What do we do? And I think that we also have to. Remind ourselves to take deep breaths and take a step back and know that all the time, everything ain't about us. Parents are, you know, I think about that often, like parents are coming to a school through traffic.

Now, when I'm driving to places and I'm in traffic, I have to put myself, I had to do that three seconds. Now, let me think about when I'm driving through traffic and dang, when I do know how it is, when I'm trying to get somewhere and it's like everybody want to drive crazy at the last minute. And I done cussed out three people in my head because I don't want to say it out loud because if I start to say it out loud.

So just thinking about how it can, I try to be relatable to people, even growing up here in Georgia and being around, you know, white people who would classify themselves as rednecks and they believe in their Confederate [00:45:00] flag. Well, I have to teach your students. And so how do we, you know, bridge the gap? A lot of different philosophies are, you know, the man got to be macho.

The women need to take care of the kids. And I'm like, well, here's the reality. Every man ain't going to be a construction worker. All right. So how do you not throw away your son who doesn't want to be the construction worker, he can still work. On a construction site because you need an accountant. Don't you need somebody, you know, HR

Dr. Asia Lyons: side, right?

Like you need somebody

Jason B. Allen: and you need somebody you can trust. You also need somebody who can run fast and be like, hey, you know, there is a fire down the way in this coming, you know, you need that, right? So you got to find a place for everyone who may not be that builder in a lot of. Men, whether they white, black, whomever, having that conversation with them so that I don't want to throw away, it may not even have anything to do with their sexuality.

Also how we define manhood, like I am a nerd. What's wrong with being a nerd? Like I like, that's me that I like to read. I like to research. That's me. [00:46:00] I don't want to be out there playing basketball. I want to be researching and figuring out how did they actually build this thing so I can go build it.

Right. You got to be able to make space for everyone and I'm just sharing that in this space and how we engage people with policies, how we engage people, every black teacher is not an abolitionist teacher, right? Yes. Every white teacher is not racist. You know, just helping people to not, this is something I used to do, I have to, saying used to is really hard, but.

One of the things I used to do with my students is break down stereotypes by breaking down generalizations, and I would share a story about Papi, who was my great grandfather, and when he served in the Air Force, and just, you know, being a part of the service, and This country and serving overseas and coming back and those realities and, you know, how you deal with things, he told me a lesson about labels and I stick with this even to this day about not subscribing to labels because people can label you as all of these things, but it's what [00:47:00] you choose to live up to and what you hear your inner voice or what you hear.

You know, a higher being speaking to you as to who you are and what you're called to do. You know, in this world, if you subscribe to everybody else's label, you'll never be what you were designed and intended to be. And so I think about that when people do a lot of generalizations. We saw this with the election where all teachers felt this way.

All Black people feel this way. And Black men did this. And we get caught up in culture wars and distractions when we get caught in generalizations. But if we take those deep breaths. You know, kind of thing and see the humanity in everybody that we can make better decisions on how we navigate ourselves in the space.

And that's what I teach. Or that's what I would teach students. And I still do. I teach to adults now.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Your heart is there. I feel it. I feel like, you know, we talk about this on the show a lot, that people find their way back to youth in so many different ways. Yes. And your heart's still there. We definitely a hundred percent hear that.

So maybe [00:48:00] it's not necessarily a full exit, maybe it's just a pause, you know, a pause interview.

Jason B. Allen: Maybe just a pause and, you know, stay tuned to educational entities. I have my next book and workbook coming out, you know, in the series. I also have a book, Students for Equity, that again, really showcases my journey with student engagement and how those things have You know, help me as an educator to help hundreds of students, like change their academic pathways and how they successfully navigate through them.

And so, you know, some of these books will be free eBooks. That's what I'm saying. Stay tuned to, you know, my website because. It'll be an alignment to the Speak Black Man podcast, but there are books that you can buy. But there'll also be eBooks because I believe that so many of these journals and things that I have, you know, can be free resources to people who really need immediate change, ideas, you know, et cetera, so forth.

Dr. Asia Lyons: I love that. So I think I [00:49:00] have a few more questions. The next question I want to ask is, Is there a Black educator or educators that you would like to shout out on the podcast?

Jason B. Allen: Oh, yeah, I have so many educators that I would definitely shout out. So first of all, I'll start with my cousin Ashton, who is teaching in Philly.

He was at the BMAC conference. AJ minor foundation. You can check him out, look him up. I would definitely shout him out, you know, because of course I got to start with my own family. My sister's an educator in special education. So shout out to her. I mean, first of all, my husband is an educator, engineering teacher, and like the number one, I would say e sports and, you know, e gaming coach.

He's won several years in a row. Several of my cousins who are principals are people that I would definitely shout out now, my favorite teacher of all time. One of my good childhood friends, father's Mr. Gordon, he taught my [00:50:00] siblings, my cousins. All of us. He was my first black male teacher and, you know, to be quite honest, a lot of my incorporating, you know, civic engagement and the history of Atlanta or like just black history and my lessons that came from Mr.

Gordon. Mr. Gordon taught us about Alley Pat and walked us by his. Well, it's not there any longer, but it was a mansion on MLK, like right down the street from my school in the hood. And so he was like, yeah, Ali Pat was the first black DJ that became a millionaire. And, you know, he housed, you know, Dr. King and Malcolm X and different leaders in the basement of his home.

You know, to kind of hide them away. And I was like, Black people had basements and like three level homes on a main street with a driveway. And like, it was phenomenal. But that was a Black male teacher who was like, Hey, now I'm gonna teach you guys this. And this is how it connects to citizenship. Why you should, I thought that was brilliant.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Yeah.

Jason B. Allen: To be honest, it really was. Cause it made me. [00:51:00] You know, excited about the community and like wanted to learn more and be engaged. And so just thinking about teachers like Mr. Gordon, who inspire us at young ages, and you never know how you're going to inspire anybody. So I definitely have to shout out Mr.

Gordon.

Dr. Asia Lyons: I love that. Last question. You're all over the place. You're doing things. You're meeting people. You're at the conferences. But for you, what does it mean to be well? Let me tell you. For

Jason B. Allen: me, what it means to be well is being smart about your health. And listen, I picked this up that quick because I'm actually reading and studying this.

And so, For me, mental health and wellness is taking time to give back to yourself. A big part of giving back to myself is reading, focusing on my mental health. I'm looking right now at, you know, my weight set. I never had time to go to the gym. I never made time to work out, but I was intentional because if I'm going to study in here or be doing conferences or doing papers, [00:52:00] then I got to give some time to actually work out.

And You know, exercise. And so those are things I wish I could show you guys some of the plants that are in my office. I also garden, right? Gardening for me and really being in the yard per se. Being able to spend time with the earth and also with the spirit realm, grieving those that have gone on to a different dimension, but also showing thanks and how, you know, we still have those of us here that are growing and building.

So really intentional about spending time in the earth, outdoors, exercising. Protecting my mental health. I will also say this. The black people get off of social media all of the time we spend on social media reading mess. And it's like junk food. Really? You put in all of that in your mental. And it is impacting your spirit and your emotion all of that time that we spend on social media and we ain't called cousins that we haven't talked to in years, or we haven't really [00:53:00] even called siblings or people who we love.

And so if I could be on social media and you know, these iPhones and these other contraptions, they have all these fancy apps that can track everything. Look at, I'm just challenging us as you asked me this question on mental health or how I'm taking care of myself and wellness. This is what I'm doing.

I'm tracking. How much time am I working? Uh, how much time am I on social media? Cause baby, if I'm giving everybody else the best of me, then I need to be able to say, I talked to my mama, my daddy, my grandparents, my sisters, people who I love like spending time with my dog, checking in on my neighbors, sitting in silence.

How long did I just spend time with myself? Cause if I'm giving the best of me to everybody else, That I don't have anything to really give back to me. So parents, think about that with your children. If I'm giving the best of my job or jobs, if I'm giving the best to social media and being engaged, and then I don't know what my child's favorite color is or what, you know, song that they like to, hey, [00:54:00] you know, use these apps to the betterment of you.

And so that's what I would say I'm doing for. My mental health is really checking more out of the reality, social media and reality TV aspect of life. under this administration and really checking more into, you know, being connected with the earth, being connected with spirit and eating healthy and exercising.

Cause let me tell you, if you go survive 2025, you better start figuring out a way to not be eating out and eating at the house

Dr. Asia Lyons: and drinking some water and drinking water

Jason B. Allen: and drinking water. Yes. Drinking water. Shout out national parents in you, but yes, drinking water. Yeah. That's my smile.

Dr. Asia Lyons: Yeah, that's perfect.

That's exactly right. Everything that you just said, you know, you're a plant parent. I'm also a fellow plant parent. So like taking care of your plants and being out in nature, drinking water, taking care of yourself. And that consistency is really important, whether we're in the classroom or not. I thank you for your time, Jason.

Yes,

Jason B. Allen: thank you.

Dr. Asia Lyons: This was [00:55:00] fantastic. People want to reach out. You've talked about your books, you've talked about your work. If they need to reach out to you, they want to talk to you, find out more about what you're doing in community. Where could they find you?

Jason B. Allen: Awesome. I'm at Professor JBA on my social media platforms, or it may be under J.

Burke Allen, because that's my name, right? But if you Google me, you'll see educationalentities. com comes up. You'll be able to connect to ETV, which is the YouTube channel with all of the podcasts or like the morning show, my students podcasts, like virtual events that I may do. You can find all of those things there, educationalentities.

com. You can get my book, all of that. You can connect with me if you want me to come and speak. All of that. Yeah. And educationalentities. com is the best way to connect with me. And I look forward to connecting with everybody.

Dr. Asia Lyons: All right, folks, you heard it. Check him out. You know, have him come to your community to speak.

You got a small taste here for free, but he don't give everything out for free. [00:56:00] So make sure you connect. Well, we'll talk to you later. Peace. If you've enjoyed this episode of The Exit Interview, a podcast for Black educators, I'm sure you'll love similar content in the Alive Podcast Network app. That's right.

We've joined a podcast network. Plus, you can support this podcast and enjoy ad free listening to nearly 100 other Black hosted podcasts. Head on over to the Live Podcast Network today.

ProfessorJBA

Jason B. Allen has worked in education for over twenty (20) years as a teacher and educational leader serving students, families and communities.

He is a longtime advocate for male engagement and building the work of increasing the number of male educators or color in classrooms and boardrooms.

His podcast, Speak Black Man, focuses on ways to recruit, retain and empower Black men, families and communities.

Jason created educational entities, an educational consulting company to provide resources, training and support for those seeking improved educational systems.

He is a member of the Association of American Educators (AAE) Georgia, Profound Gentlemen and is the National Director of Partnerships for the National Parents Union.